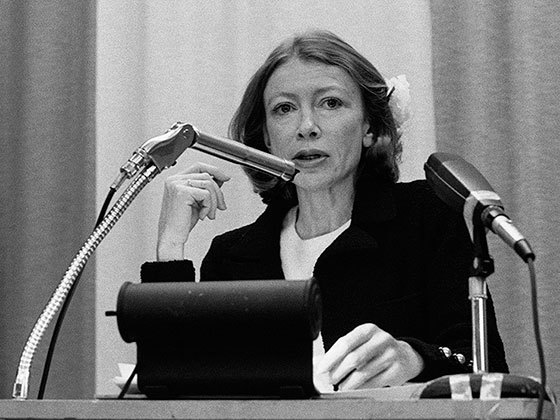

The novelist E. L. Doctorow, who died in New York City last week at the age of 84, was a friend to The Library of America over the years, having contributed an introduction to the LOA edition of Jack London’s The Call of the Wild and spoken at a number of LOA events.

We’re now pleased to present a video highlight of Doctorow’s tribute to Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick at The Library of America’s twenty-fifth anniversary celebration in New York City on May 17, 2007. The clip is followed by the complete text of Doctorow’s remarks. (The complete video is available here.)

Video: E. L. Doctorow on May 17, 2007 (1:40)

Literary history finds a few novelists who achieved their greatness from an impatience with the conventions of narrative. Virginia Woolf composed Mrs. Dalloway from the determination to write a novel without plot. And then James Joyce, of course, who proved himself in the art of narrative writing before he committed his assaults upon it. The author of the sterling narrative Typee and Omoo precedes Joyce with his own blatant subversion of the narrative compact he calls Moby-Dick.

Yet I would guess that what Melville does in this novel is not from a grand preconceived aesthetic but from the necessity of dealing with the problem inherent in constructing an entire 19th-century novel around a single life-and-death encounter with a whale. The encounter clearly having to come as the climax of his book, Melville’s writing problem was how to pass the time until then—until he got the Pequod to the Southern Whale Fisheries and brought the white whale from the depths, Ahab crying “There she blows—there she blows! A hump like snow hill! It is Moby Dick!” She blows, I point out to you, not until page 537 of a 566-page book—in my old paperback Rinehart edition.

A writer lacking Melville’s genius might conceive of a shorter novel, its entry point being possibly closer in time to the deadly encounter. And with maybe a flashback or two thrown in. Melville’s entry point, you remember, is not at sea aboard the Pequod, not even in Nantucket: he locates Ishmael in Manhattan—and the book is landlocked for a hundred or so pages until the Pequod in Chapter 22 “thrusts her vindictive bows into the cold malicious waves.”

I wouldn’t wonder if Melville at this point, the Pequod finally underway, stopped to read what he had written to see what his book was bidding him to do.

This is sheer guesswork, of course. I have not read the major biographies, and I don’t know what Melville himself may have said about the writing of Moby-Dick beyond characterizing it as a “wicked book.” Besides, whatever any author says of his novel is of course another form of the fiction he practices and is never, never, to be trusted.

Perhaps Melville had everything comfortably worked out before he began, though I doubt it. Perhaps he had a draft completed of something quite conventional before the writer’s sense of crisis set in. The point to remember is the same that Faulkner once reminded his critics of: that they see a finished work and do not dream of the chaos of trial and error and torment from which it has somehow emerged.

So let me propose that having done his first hundred or so pages of almost entirely land-based writing, Melville stopped to read what he had written. What have I got here?—the author’s question.

“This Ishmael—he is logorrheic! Whatever he writes about, he takes his time. With this Ishmael, if I have a hundred or so land-based pages, if I am to keep the proportion of the thing, and the encounter with the whale is my climax, I will need at least 450 pages of sailing before I find him. My God.”

So there was the problem. His sentences had a texture that could conceivably leave his book wallowing with limp sails in a becalmed narrative sea.

I will not speculate that there may have come to Melville one of those terrible writer’s moments of despair that can be so useful in fusing as if with lightning the book so far with the book to come. In any event he would for his salvation have to discover that his pages manifested not one but two principles of composition. First, a conventional use of chronological time. After all, Ahab would have to allow the crew the hunting of other whales. So there was that action. Bad weather and worse could reasonably be invoked. There was that action. As Ahab’s maniacal singlemindedness became apparent to the crew, some of them, at least, might contest his authority. Other whalers were abroad around the world. They could be met and inquired of. As indeed there are, what, perhaps eight or nine such encounters with other ships. Given this pattern, a habitual recourse of the narrative, we readers today can make a case for Moby-Dick as a road novel.

But while in these first 105 pages Ishmael’s integrity as a narrator is maintained, and the set-up for the voyage suggests an assiduous and conventional narrative, there is something else, possibly less visible, a second principle of composition lurking there. It would come to Melville incipiently as a sense of dissatisfaction with his earlier books, and their gift for nautical adventure. While we may know that there is nobody, before or since, who has written better descriptions of the sea and its infinite natures and the wrathful occasions it can deliver, to Melville himself this talent would be of no consequence as he contemplated the requirements of his Moby-Dick, and felt the aching need to do this book, to bring it to fruition out of the depths of his consciousness—to resolve, into a finished visionary work, everything he knew.

So he looks again at his Ishmael. And he finds in him the polymath of his dreams.

Ishmael has read his Shakespeare. He knows European history. He is conversant with biblical scholarship, philosophy, ancient history, classical myth, English poetry, lands and empires, geography. Why stop there? He can express the latest thinking in geology (he would know about the tectonic plates), the implications of Darwinism, and look, his enlightened cultural anthropology.

“I can make this fellow an egregious eavesdropper, so talented as to be able to hear men think, or repeat their privately muttered soliloquies verbatim.”

And it is a fact that no sooner are we at sea, in Chapter 24, does Ishmael step out of time in a big way and give us the first of his lectures on whaling. His big gamble has begun, to pass the time by destroying it, to make a new thing of the novel form by blasting its conventions.

I know this to be true: Herman Melville may have been theologically a skeptic, philosophically an Existentialist, personally a depressive, with a desolation of spirit as deep as any sea dingle—but as a writer he is exuberant.

He will load his entire book with time-stopping pedagogy—he will give us essays, trade lore, taxonomies, opinion surveys, he will review the pertinent literature—he will carry on to excess outside the narrative.

It interests me that Ishmael, who is the source of Melville’s inspired subversion of the narrative compact, must therefore be himself badly used by the author. Ishmael is treated with great love but scant respect—he is Ishmael, all right, in being so easily cast out, and if he is called back it is only to be cast out again. I wonder if it was not a private irony of his author that the physically irresolute Ishmael, with roughly the same protoplasm of the Cheshire cat, is the Pequod’s sole survivor.

And then of course the excess touches every corner, every nook and cranny below deck, every tool and technical fact of the life aboard the Pequod, and everything upon it, from Ahab’s prosthesis to the gold doubloon he nails upon the mast. The narrative bounds forward from the discussion of things. So finally we look at the details and discover something else: whatever it is, Melville will provide us the meanings to be taken from it.

This suggests to me the mind of a poet. The significations, the meaningful enlargements he makes of tools, coins, colors, existent facts, even the color of the whale are the work of a lyric poet, a maker of metaphorical meanings, for whom unembellished linear narrative is but a pale joy.

Moby-Dick is a big kitchen-sink sort of book into which the exuberant author, a writing fool, throws everything he knows, happily changing voice, philosophizing, violating the consistent narrative, dropping in every arcane bit of information he can think of, reworking his research, indulging in parody, unleashing his pure powers of description—so that the real Moby Dick is the voracious maw of the book swallowing the English language.

The novel’s greatness is not negated by the fact that our culture has changed and we now no longer hunt the whale as much as we try to save it. In fact, according to newspaper reports, whale watching, not hunting, is now the greatest threat to their well being, or whalebeing. Going out in sightseeing boats to frolic with the whales is a bigger industry now, producing more income, than fishing from them, and threatens to disrupt their migratory patterns and thus their organized means of survival. In fact, one can imagine Moby-Dick as possibly a prophetic document, if one day a Leviathan rises from the sea in total exasperation of being watched by these alien humans, humans who once at least in hunting them were marginally in the natural world, but now in only observing them are in that realm no longer, and so rightly destined for the huge open jaw, and the mighty crunch, and the triumphant slap of the horizontal flukes.

But whatever the case, I can assure you Ernest Hemingway was wrong when he said American literature begins with Huckleberry Finn. It begins with Moby-Dick, the book that swallowed European civilization whole, and we only are escaped alone on our own shore, to tell our tales.

© 2007 E. L. Doctorow. Used by permission.