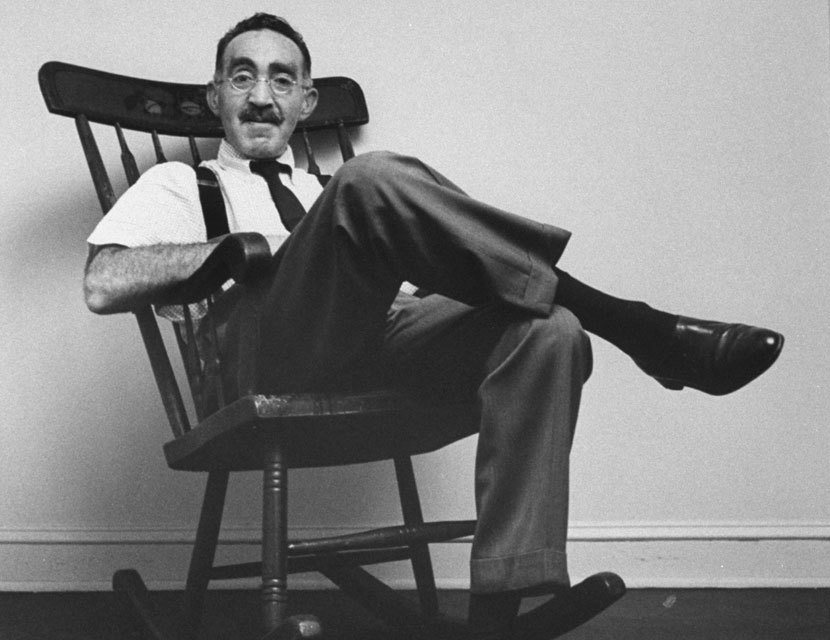

Another classic humorist enters the Library of America series with the arrival this fall of S. J. Perelman: Writings. Although Sidney Joseph Perelman (1904–1979) co-wrote two Marx Brothers movies and won an Academy Award for his screenwriting on the 1956 Hollywood extravaganza Around the World in Eighty Days, he remains best known for the short comic pieces—Perelman called them feuilletons—he contributed to The New Yorker during its golden age of humor, in which his penchant for wordplay, witticism, spoofery, self-deprecation, and plain zaniness are on full display.

Editor Adam Gopnik has collected the best of these pieces, including Perelman’s parodies of books and films, his biting social satire, autobiographical pieces, and a selection from the celebrated “Cloudland Revisited” series, in which Perelman reminisces about books and movies encountered in youth before describing the rude shock of revisiting them as an adult. Also included in this volume are Perelman’s acclaimed play The Beauty Part (1962); profiles of the Marx Brothers, Dorothy Parker, and Perelman’s brother-in-law Nathanael West; and a selection of letters written to correspondents such as Groucho Marx and Paul Theroux.

Adam Gopnik is a staff writer at The New Yorker, for which he has written since 1986. He has three National Magazine awards for essays and for criticism and a George Polk Award for Magazine Reporting. In 2013, Gopnik was awarded the medal of Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters, and in 2021 was made an Officer of the Légion d’Honneur. The author of numerous best-selling books, including Paris to the Moon, he lives in New York City. In the following Q & A, he offers some insights into Perelman’s singular prose style and some of the editorial choices behind the new collection.

Library of America: By his own account S. J. Perelman was a practitioner of a literary form, the feuilleton, that may not be familiar to a lot of readers in the twenty-first century. Can you discuss the genre of the feuilleton and describe what Perelman brings to it that’s so unique?

Adam Gopnik: Well, feuilleton was Perelman’s own word, seemingly borrowed from the French—well, duh, as the kids say. He was reaching for a self-description that would seem a little crunchier than the New Yorker “casual,” which sounds . . . too casual for the sheer length of his pieces, yet a word that didn’t pretend to the academic weight of “satire” and certainly wasn’t anything like a short story. Longer, more rococo, and more complexly comic than the charming quick hits of a Benchley or a Will Cuppy, it usually began with a lengthy epigraph, an introduction to set the situation, evolving often into a playlet, only to return to the original set-up in the end. It was a form that Perelman perfected and was then brought to something like abstract art in the hands of Veronica Geng. Now, it seems, as I remark in the introduction, finished though not exhausted; the new humorists, whether Andy Borowitz or Patricia Marx, are again quick hitters, from force of space, perhaps, as much as necessity of art.

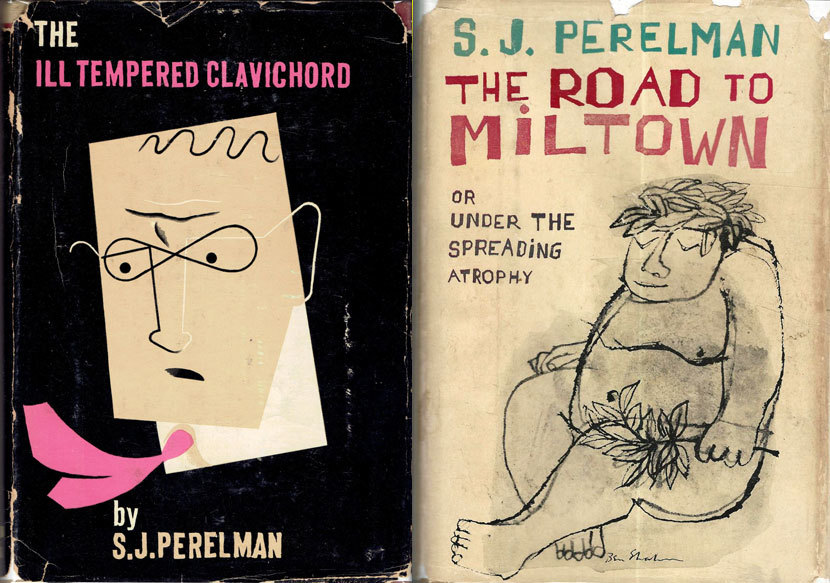

LOA: For years the classic Perelman collection was a book called Crazy Like a Fox, which first appeared in 1944 and was regularly reissued after that. But in your introduction to the LOA volume, you argue that Perelman’s great phase really begins post-1945. Is this selection, then, a new “definitive Perelman?” And what distinguishes the later work from the period covered in Crazy Like a Fox?

Gopnik: Perelman never wrote badly, of course. But, yes, in reading through the work, for all the joys and gems of Crazy Like a Fox—including the great, genuinely Joycean “Scenario,” a stream of consciousness representation of a movie-pitch meeting that, extended to novel length, might have changed Perelman’s life, and American letters—I sensed a definite coming-into-greatness in the postwar writing. Two reasons for this, surely: one, that he was settled into the magazine [The New Yorker], with a sympathetic editor in William Shawn, and felt confident that his wildest chains of connection and the most recherché allusions, his craziest foxiness, if you like, would be relished and permitted and printed, which is all a writer cares about.

The other reason, more profound, was that the circumstances of postwar America—the sheer overcharge of advertising, accelerated by shared prosperity and the rise of television—gave his great subject, American vulgarity, a kind of omnipresence that it didn’t quite have through the more parched Depression years. If your work in life was satirizing the desperate pretensions of American commercial culture, the fifties was the time to do it.

And then he was sufficiently far removed from his own youth to be able to retrospect it comically, even kindly, without nostalgia, an emotion that produced the wonderful “Cloudland Revisited” series, in which he looked again at the trashy but endearing movies and books that had shaped his consciousness. Meanwhile, he was just beginning the series of travel pieces that I find funny but not quite as essential, and which came to dominate his work later on. So yes, Perelman in the fifties was Perelman at his best.

LOA: In your introduction you note: “Perelman is a writers’ writer in the literal sense that his rhetoric—his style—always emerges from his reading. Every sentence written references some earlier, once-read sentence…. he is always a Kipling adventurer, a Conan Doyle detective, a Maupassant boulevardier, dressed British and thinking in Yiddish.” That suggests a certain chameleonic quality, and yet Perelman sounds unmistakably like himself in any paragraph you read of him. How do we account for this seeming paradox?

Gopnik: Well, it’s in the stitch-work, surely? It was his ability to make these styles collide, not his ability to pastiche them alone, that gave his work its inimitable tone. Hold on, while I put this doxy—no, it’s a dog—off my lap long enough to go hunt up a paragraph (as he would have said). The opening stanza, say, of “Hello, Central, Give Me That Jolly Old Pelf”:

I was teetering on my heels the other evening before our fireplace, quaffing a tankard of mulled ale, puffing on a churchwarden, and waving both in unison to a rousing stave—altogether a frightfully good simulacrum of one of Surtees’ English sporting squires—when a wayward spark from the hearth suddenly ignited the skirts of my shooting coat. My whipcords stood out like veins, and in consequence I was obliged to remain hors de combat the next couple of days, propped up on my elbows and reading the most mealy prose.

There we have a parody not just of Victorian style (“frightfully good”) but of Victorian imagery—that Surtees print—suddenly colliding with a Groucho-style reversal of genius (“My whipcords stood out like veins”) pushing forward to a narrative point; we know that whatever he is reading will become the subject of the piece. It is the rush from one manner to the next that makes the Perelman style.

LOA: An appreciation in the Forward prompted by LOA’s new edition argues for Perelman as “one of the greatest avant-garde writers in the history of American literature.” Comment? Some people may not believe that a writer who makes us laugh out loud can also be a great avant-gardist.

Gopnik: “Avant-garde,” like “radical,” is one of those empty words that make critics feel avant-garde and radical themselves more than they point to any actual literary accomplishment. (There’s plenty of bad “avant-garde” writing and lots of foolish radicalism.) Perelman was indeed a more audacious and original stylist than many writers of greater pretension to prizes in his time. But, like all great satirists, he was essentially conservative, with a clear set of values—lucidity, elegance in personal style, British suits, for God’s sake—that seemed to him under perpetual assault. (And he was, like all satirists, secretly grateful for the assault, as it gave him a subject.) But his instinct is always preservative, and the extravagance of his prose is the extravagance of a dandy seeking perfect form, not the extravagance of a bomb-thrower making fires.

LOA: This collection includes in full Perelman’s 1962 play The Beauty Part, widely considered the most successful of the five Broadway plays he wrote or co-wrote. Do his distinctive traits—the allusiveness, for instance, and the Yiddishisms—translate to the stage, or was he working in a different register altogether?

Gopnik: Indeed, yes, Perelman writing for the stage or screen is what professors call “problematic.” Though he made his living writing scenarios and longed to write a successful play (or musical), his work, exactly because of its elegant extensions, its formal length, always feels a bit . . . stiff when spoken. His writing arm, so to speak, had become so twisted throwing his inimitable changeups and curves that when he had to stand up and throw fastballs at an audience it failed him. Movies and plays benefit from compression and forward movement, neither of which interested him. Around The World in Eighty Days now seems remarkably stilted. However, I’ve seen The Beauty Part on stage several times, and it can work in the same way his great Marx Brothers films work—the performers throw enough anarchic energy into the text to allow us to delight in the writing while the story gets pushed ahead by the actors.

And One Touch of Venus, his collaboration with Ogden Nash and Kurt Weill, still works on stage; the musical theater, intrinsically stylized, should have been his natural home, though the crazy short-circuitings of Broadway kept that from happening. (How sad that a collaboration with Cole Porter, on an “Aladdin” story, was cut short by Porter’s death, depriving us of their joint work and also, perhaps, killing off in the cradle that other, later Disney version.)