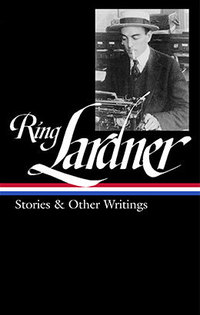

Writer and humorist Ian Frazier, a frequent contributor to The New Yorker and the author of many books (including the best-selling Travels in Siberia) spoke with us recently about the newly published Ring Lardner: Stories & Other Writings, which he edited for The Library of America.

LOA: Why should people read this book? Why should they care about Ring Lardner?

Frazier: Ring Lardner wrote like nobody else, caught the feel of his era like nobody else, and knew how to make people laugh with a voice or a plot change-up or a small misspelling. He was a major figure in twentieth-century American letters.

LOA: Contemporaries called the language of Lardner’s stories “Lardnerese.” What is Lardnerese? What were his special gifts or contributions as a stylist?

Frazier: As this anthology shows, Lardner heard his own voice with perfect clarity from the time he was a teenager. Just as clearly, he registered the way people around him talked in the Midwestern places where he lived and where he worked as a young man. He had a genius’s ear for living speech, and he went beyond the range of ordinary orthography to capture that speech in writing. His typewriter was like a John Cage prepared piano—it made sounds, and produced corresponding narratives, that were all its own.

LOA: How did your sense of Lardner as person or writer change while working on this book?

Frazier: He was an amazing man—passionate and ice-cold simultaneously. As I learned more about him I saw him as an enigmatic, cold American—like a Clint Eastwood character in a Western, or like D. H. Lawrence’s definition of an American: “isolate, and a killer.” Those qualities come out especially, I think, in Lardner’s brilliant, often hilarious, and always merciless stories. But Lardner was a good friend and a gentle family man, too. That is apparent in his letters and in his biography. He had outstanding, remarkable children.

LOA: If Lardner were around today, what do you think he’d be doing for a living?

Frazier: He would be writing—no one with a gift as great as his would be able to ignore it. But I’m not sure what. If he were around today, or if Fitzgerald or Hemingway or Harold Ross were around today, today would be something other than it is.

LOA: Do you detect his influence on other writers?

Frazier: Definitely. On Thurber, for one. He laid out a Midwestern scene for Thurber to populate with Thurber characters. Lardner’s middle-class settings and small-town plots presage O’Hara, Updike, and Cheever. And Lardner’s view of the psychic obtuseness and frailty and in-spite-of-themselves lovability of baseball players has influenced the way generations of writers have portrayed athletes.

LOA: Best discovery while working on book?

Frazier: I loved rereading pieces, well-known and not, that I hadn’t looked at for a long time. I had never seen his World War I writings, and I really enjoyed those. I hadn’t known how much the war had been a part of his early career and life. I admired Ellis Abbott, whom he courted in Lardnerian prose and who married him—luckily for him. She was a Midwestern aristocrat of the first rank, and a really cool person.

LOA: What do you think readers will find most surprising?

Frazier: Maybe the extreme, ahead-of-its-time modernism of his short plays.

LOA: Favorite piece in collection?

Frazier: The Young Immigrunts! This is a magic piece of humor writing. “ ‘Shut up,’ he explained,” is as funny as it is possible to be in only four words. But every line in this story is a magic trick. The only difference between this story and what actual magicians do is that their tricks can be explained. I’ve looked at The Young Immigrunts dozens of times, always with the same mystified delight, and I still couldn’t tell you how it was done.