Last October, the first annual Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film was awarded to Flannery, a new nonfiction film about Flannery O’Connor that Ken Burns called “an extraordinary documentary that allows us to follow the creative process of one of our country’s greatest writers” and Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden greeted as “a beautiful and thoughtful reflection about the power of words and contemplation.”

Flannery covers everything from O’Connor’s Catholicism to her sexuality, her short stories to her cartoons, her experience in the Civil Rights–era South to her life-ending battle with lupus. In addition to its striking animations and visuals, the film also hosts an impressive lineup of celebrity testimonials—from actor Tommy Lee Jones to The Color Purple author Alice Walker—and leaves its audience feeling an urgent need to revisit her fiction.

Flannery was codirected by Elizabeth Coffman, associate professor at Loyola University Chicago, and Mark Bosco, Jesuit priest and Vice President for Mission and Ministry at Georgetown University. Having screened the documentary to wide acclaim at college campuses and film festivals across the country, they are currently in the process of expanding its public availability. They agreed to talk about the film with us via email.

Library of America: Congratulations on winning the first ever Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film. How does it feel to know that your documentary received such praise from Burns, not to mention the Library of Congress?

Elizabeth Coffman: As I exclaimed at the prize ceremony in DC, “This is better than winning an Academy Award!” To have Carla Hayden (the Librarian of Congress) and Ken Burns (the Ken Burns) both celebrating Flannery felt like a dream. My first thought was how pleased O’Connor would have been to be celebrated in the halls of the Library of Congress. Pleased, but maybe not too surprised (O’Connor knew she was a good writer!).

Mark Bosco: When Elizabeth called me to tell me that she just got off the phone with Carla Hayden, I was a bit stunned. I knew we had put the film in for consideration, but I had sort of forgotten about it as we were still trying to raise money for some of the post-production costs. So I was both heartened that we were chosen and glad that the monetary prize could help us finish and promote the film. But on the night of the award ceremony at the Library of Congress, Hayden and Burns both told us that they had not discussed which film was their choice and were excited that they both picked Flannery.

LOA: What documentaries or documentary filmmakers have most influenced you?

Coffman: That’s a tough one. There are so many! Frederick Wiseman, Titicut Follies; Barbara Kopple, Harlan County, USA; George Stoney, All My Babies; Steve James, Hoop Dreams; Pamela Yates, Granito; Ken Burns’s The Civil War—just to name a few!

Bosco: Though I am a big fan of documentaries, I came very late to documentary filmmaking. Indeed, you might say that Flannery is a “passion project” for me, so bringing on Elizabeth as a collaborator has taught me a lot. I had to trust Elizabeth to guide me through the process.

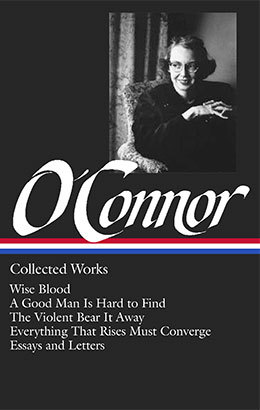

| O’CONNOR in LOA |

|

| Flannery O’Connor: Collected Works |

LOA: Flannery features interviews with an array of contemporary writers and artists—Tommy Lee Jones, Alice Walker, Tobias Wolff, Hilton Als, Mary Karr, Alice McDermott—discussing O’Connor’s fiction. How did you arrive at this lineup? What were the most surprising moments of the interviewing process, and were there any noteworthy segments that didn’t make the final cut?

Coffman: Mark, an O’Connor scholar, did a wonderful job identifying and recruiting most of our new interview subjects. I was a little surprised at how quickly people agreed to be interviewed! Writers really love O’Connor and recognize that she deserves more media attention.

Alice Walker, speaking about her wonderful essay, “Beyond the Peacock: The Reconstruction of Flannery O’Connor,” notes how important it was to discover that a nationally successful writer (a woman!) lived just twenty miles up the road from her in Georgia, and she could take her mother to lunch across the street from O’Connor’s home.

On the cutting room floor is a moment when Walker discusses O’Connor’s Catholicism and its invisibility in the South, along with the “purity” and safety that people of color felt with their churches, many hidden in the woods. Segregated spaces, yes, but crucial for community survival.

Bosco: Early on, when Elizabeth and I decided to move forward with the film, we began putting together a list of artists, critics, performers, and directors who had written or spoken about O’Connor’s significance for them: Tommy Lee Jones and Conan O’Brien did their Harvard senior theses on Flannery O’Connor and came to appreciate her satire and her often violent aesthetic turns. Alice Walker and Hilton Als each wrote superb essays on the importance of O’Connor’s work in their own critical development and have articulated why her work is important for American arts and letters today.

One thing I am sad didn’t make it was Tobias Wolff’s comment—made when we had stopped filming him—that when he was director of Stanford’s MFA program, he always had students grapple with O’Connor, because he knew of few better authors when it came to the craft of writing short stories. He said something to the effect that one needs to go through Flannery O’Connor’s work, not around it.

LOA: The film includes archival footage of an interview with O’Connor in which she says that “A serious fiction writer describes an action only in order to reveal a mystery.” What mysteries do you think O’Connor’s fiction reveals?

Coffman: O’Connor’s fiction touches on the crazy, obsessive desire to tell stories, even when, or especially when, the whole world is laughing at you. Mysteries are revealed when the mother you’ve made fun of for so long dies in front of you; when the Bible salesman steals the wooden leg you need to walk; when an ”accidental” death that you could have prevented happens. When that violent moment of narrative redemption hits—when that “know it all” character gets humiliated, or that Polish refugee gets run over—O’Connor leaves her readers wondering why they suddenly care so much about the murderers.

Bosco: Novelist Mary Gordon says in the film that “Flannery O’Connor is one of the few writers who is not afraid to look into the darkness.” And I think that darkness haunts us today. Her stories are redemptive acts, sending us, the readers, to look inside ourselves, to that mysterious place that suggests that what falls can also be restored.

LOA: What is it that makes O’Connor’s Gothic stories set in the American South so appealing to generations of readers from all walks of life?

Coffman: O’Connor’s twisted sense of humor makes her a favorite in my opinion. Besides being a wonderfully cinematic writer, you can hear O’Connor’s stories. Her unsentimental view of bad behavior combined with her ability to capture Southern voices and colloquial expressions will leave the reader laughing and then choking on that laughter.

Bosco: Well, she is funny. Her observations about the manners of Southern life are terrific satire. And her stories feel almost contemporary, as we see parallels between her time during the dismantling of the Jim Crow South, and our times with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, or the white supremacist movements looking for legitimacy.

LOA: Many readers may be familiar with O’Connor’s frequently anthologized short story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” but your documentary considers a range of her work. Other than “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” what one story would you recommend to new O’Connor readers, and why?

Coffman: It depends on the day of the week! I always love reading “Good Country People.” A great place to start! O’Connor named “The Artificial Nigger” as one of her favorite stories, and it’s both powerful and painful to read. O’Connor’s careful deconstruction of the “n-word” in this story—its repetition as a racist tool passed down from grandfather to grandson—keeps it sadly relevant. And I’m a fan of “The Late Encounter with the Enemy,” about a girl-crazy Civil War veteran at the 1939 Gone with the Wind premiere in Atlanta.

Bosco: I think the stories that most resonate with our contemporary moment are also her greatest works. If I had to pick three, they would be the following: “Parker’s Back,” because of our modern fascination with tattoo culture; “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” because the racial tension in the story mirrors the racial tensions in our country; and “Revelation,” because it is just the most perfect American short story there is. I know I am biased, but every time I read and teach these stories, I am amazed at the way they touch those mysterious places in my head and heart.

View the official trailer for Flannery (1:29)

Visit the official Flannery website for information on upcoming screenings and more.