In February 2009 Little Brown & Company published Flannery: A Life of Flannery O’Connor by Brad Gooch, the first major biography of the writer since her death. In connection with The Library of America’s 1988 definitive edition of Flannery O’Connor: Collected Works, Rich Kelley conducted this exclusive interview for The Library of America.

LOA: In a recent review in The New York Review of Books of a number of works by or about Flannery O’Connor, including your biography, Joyce Carol Oates notes that “in 2008, the Modern Language Association catalogued 1,340 entries under ‘Flannery O’Connor,’ including 195 doctoral dissertations and several book-length studies.” She also remarks that “no postwar and posthumous literary reputation of the twentieth century, with the notable exception of Sylvia Plath, has grown more rapidly and dramatically than that of O’Connor, whose work has acquired a canonical status since her death in 1964.” What is it about her work that today’s readers and scholars find so appealing?

Gooch: Flannery O’Connor truly does seem to have found her moment with us in the twenty-first century. I am always struck by how many of her stories read as if they were written just last week. Those short, abrupt sentences, which appeared preternaturally “plain” when she wrote them, now seem pitch-perfect in their blunt directness. They give us the news that we need to hear. Their content is fresh and current, too. We are no strangers to tales of extreme violence told by news commentators; sound bites from religious fundamentalists lost in the byways of theology are familiar enough. O’Connor’s apocalyptic tall tales tell us much about our own end times. Mixing faith and grace with violence and dark comedy, her shell-shocked attitude is neither sentimental nor dated.

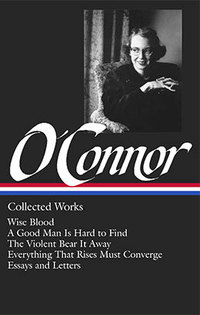

As Oates indicates, though, she took us a bit by surprise. At the time of her death in 1964, with a second volume of short stories, Everything That Rises Must Converge, still unpublished, she was viewed more as a “minor” writer, a sidebar to Faulkner. Yet unlike many authors celebrated in their lifetimes who fade once the lights generated by the publicity machine are turned off, O’Connor only endured and flourished. Her Complete Stories was awarded a posthumous 1972 National Book Award. A collection of her letters, The Habit of Being, appearing in 1979, edited by her Library of America editor Sally Fitzgerald, was a revelation. However commercially challenging her favored genre of short fiction, her stories have fit handily into anthologies read now by a few generations of college students. To some surprise, Collected Works, her 1988 Library of America edition—the first inclusion of a postwar woman writer—widely outsold Faulkner’s, published three years earlier. Fast-forwarding to 2009, my “Google Alert” for “O’Connor” brings daily evidence that the phrase “like something out of Flannery O’Connor” is now accepted shorthand, like “Kafkaesque” before it, for nailing many a funny, dark, or askew moment.

LOA: O’Connor took six years to write Wise Blood and another seven years to write her second novel, The Violent Bear It Away. How did what she wanted to achieve in her novels differ from what she wanted to do in her stories?

Gooch: O’Connor treated novels as arduous homework assignments. She probably deserves an “A” for her two novels, Wise Blood and The Violent Bear It Away, but they gave her (and lots of critics, too) trouble. Wise Blood grew out of a story she was writing at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop—“The Train.” She was partly inspired to make the attempt, too, by a Rinehart prize to fund a student novel, with an option to publish. Her “first reader” Caroline Gordon warned her before she began The Violent Bear It Away not to let her publishers “bully you into writing a novel if you don’t feel like it.” Originally titled You Can’t Be Any Poorer than Dead, O’Connor joked of this second “Opus Nauseous” to a friend, “Which is the way I feel every time I get to work on it.” Her models for both were short lyric novels—black diamonds such as Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym or Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts—quite unlike those macho Great American Novels published the same year as Wise Blood (1952): Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, Steinbeck’s East of Eden, Ellison’s Invisible Man. Conversely, her stories are single-shot masterworks that she often conceived as holidays from the longer haul of novel-writing. “I get so sick of my novel that I have to have some diversion” she wrote, taking a break to knock off the zesty “Greenleaf,” in which Mrs. May is gored by an amorous bull.

LOA: Collected Works includes her two published collections of stories: A Good Man Is Hard to Find, published in 1955, and the collection published posthumously, Everything That Rises Must Converge (1965), and nine stories not included in these collections. How would you characterize the ways in which the two collections, published ten years apart, differ? Do you have a favorite story?

Gooch: O’Connor worked with a limited set of elements that she arranged and rearranged in altered combinations and patterns. In that sense, her work never changed, only deepened and grew more complex, so that the second collection might not be seen as all that different from the first. Certainly the title story, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”—one of the first she wrote in her maturity—contains all of her signature ingredients: a small-minded matriarch gets her come-uppance; a demon of an escaped convict murders an entire family in the woods while spouting nihilist philosophy; grace glimmers, if dimly.

My favorite story of the second collection, “Revelation,” features classic O’Connor routines, as well: the bumptious farm lady has a textbook thrown at her by a college girl in a doctor’s waiting room. But by its end, mysterious new changes are worked: Mrs. Turpin is granted a celestial vision while hosing down her pigs. I think this gift to the matriarch—replacing the more usual matricide—marks a mellowing in O’Connor’s fiction. One critic accused me of “wishful thinking” in this regard. But I detect significant modulation in O’Connor’s last stories—“Parker’s Back,” where O. E. Parker bawls like a baby into a tree trunk, or “Judgment Day,” when a black worker peers at his white boss through spectacle frames he carved from wood and sees only “a man,” not a white man. I intuit her as having some success at finding a way through an impasse she described to a friend near the end of her life—“I can’t do again what I know I can do well”—breaking through toward “the larger things that I need to do now,” which she worried over her “capacity for doing.”

LOA: In her twenties O’Connor seems to have been desperate to escape from the confines of small-town life in Georgia, but once it became clear the kind of care her lupus would require she seems to have resigned herself to living at Andalusia with her mother, which she did with intermittent trips from 1953 until her death. Your book cites numerous instances in which she draws on conversations, incidents, friends, and acquaintances as inspirations for her work. How critical to her work was staying and living in Milledgeville?

Gooch: O’Connor understandably wished to make a run for it when she graduated from Georgia State College for Women in 1945. Her father died of lupus when she was 15; the prospect of life with her mother and maiden aunts in the Cline mansion in Milledgeville was stultifying. She had achieved some local fame as class cartoonist and budding writer and much attention from her professors. When she went north to the University of Iowa her original plan was to make a living as a political cartoonist. She soon discovered Paul Engle’s Writers’ Workshop—the first M.F.A. program in the country—and her vocation as a writer. Going on to Yaddo, living briefly in Manhattan, and then with her friends the Fitzgeralds in Connecticut, working on her first novel, she was intent on being a writer on her own. She seemed headed for a life in the greater cosmopolitan New York City area, in the style of such displaced Southern authors as Allen Tate or Truman Capote.

Forced home when she developed lupus herself at age 25, O’Connor tried to make sense of her life. Gradually she came to spin hers as a prodigal daughter story. Having left for the alluring literary life up North and then forced to return to a confining dairy farm in middle Georgia with her “beloved tyrant” of a mother, she discovered this great gift—if not her “voice,” her material in the land, folks, and talk in her own backyard. When another young Southern writer, Cecil Dawkins, later wrote her of a similar choice between sticking to her small town or moving to the bright lights, big city, O’Connor replied, “I stayed away from the time I was 20 until I was 25 with the notion that the life of my writing depended on my staying away. I would certainly have persisted in that delusion had I not got very ill and had to come home. The best of my writing has been done here.”

LOA: Harold Bloom has written about O’Connor: “It is not her incessant violence that is troublesome but rather her passionate endorsement of that violence as the only way to startle her secular readers into a spiritual awareness.” This echoes the line O’Connor writes in her essay “The Grotesque in Southern Fiction”: “There are ages when it is possible to woo the reader; there are others when something more drastic is necessary.” From her first writings O’Connor seems drawn to violence. Where does this come from?

Gooch: As a biographer, I do find some explanation for these violent tactics in her life. While still a teenager trying to make sense of the death of the father she dearly loved, O’Connor wrote a journal entry astonishing for its combination of profundity and innocence: “The reality of death has come upon us and a consciousness of the power of God has broken our complacency like a bullet in the side.” This early linking of God’s grace with violence is telling. She began writing “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” with The Misfit gunning down an entire family in the woods, after returning from Connecticut, where Sally Fitzgerald clued her in that the nature of her own illness was lupus, a diagnosis that her mother had kept from her. Fitzgerald remembered thinking, when mailed a draft in the spring of 1953, “It was no coincidence that Flannery wrote that story within months of, metaphorically, having a gun aimed at her.” O’Connor used violence to startle. She treated fiction writing as an extreme sport. But in her maturity she thought the matter through theologically, as well, coming up with a viable, if edgy, understanding of grace working through demons such as The Misfit or the pederast of The Violent Bear It Away.

LOA: Your biography closely chronicles what a devout Catholic O’Connor was: a daily communicant who enjoyed reading and discussing scholarly theological treatises. Yet she didn’t entirely discourage writers who took contrarian readings of her works. For instance, you recount her telling John Hawkes that she “liked very very much” his essay “Flannery O’Connor’s Devil” in which he finds her “authorial attitude in itself in some measure diabolical . . . that is, ‘the disbelief that we breathe in with the air of the times’ emerges fully as two-sided or complex as the ‘attraction for the Holy.’” Was it her aim, do you think, to create works that could be interpreted in antithetical ways?

Gooch: O’Connor forever crossed wires in her life and work. Conan O’Brien wrote his senior thesis at Harvard on O’Connor. One night on The Charlie Rose Show he put the riddle succinctly: “You’d think it was this bitter old alcoholic who’s writing these really funny, dark stories. Then you find out that she’s a woman and that she’s devoutly religious. It’s the opposite of what you would expect.” She definitely designed her stories to be read in a world not as given as she to literal belief in God or the devil. Such a trick was not easy and took a while to develop. While at Iowa, she sought guidance from a local priest: how could a Catholic girl be writing about snarly types like Haze Motes, who calls on a town prostitute. The priest told her she didn’t need to write for 15-year-old girls. She slowly parlayed this advice into a more sophisticated apology, borrowed from Thomas Aquinas by way of Jacques Maritain: art is a habit of the practical rather than the moral intellect. As she put it: “You don’t have to be good to write well. Much to be thankful for.”

But the issue of contrary readings of O’Connor’s fiction is compelling, and has never been raised more provocatively than by her friend John Hawkes during her lifetime. Borrowing a line of reasoning from Dr. Johnson when he claimed that Milton was “of the Devil’s party” because Paradise Lost loses its zing when Satan is offstage, Hawkes finds the “diabolical” to be the guilty pleasure in O’Connor’s work. Privately—not to Hawkes—she judged the theory “off center.” But Hawkes was not alone in the camp that felt O’Connor was not the best reader of her own work, and her theological gloss perhaps spin, whether conscious or not. Firmly planted in this opinion was her progressive friend Maryat Lee, who found dissonance between O’Connor the story writer and O’Connor the theologian. “The writing is one thing and the thinking and speeches are another,” she wrote to a mutual friend. “Jekyll and Hyde if you will. Perhaps.”

LOA: O’Connor seemed willing to respond to anyone who wrote to her, which is what led to the hundreds of letters she exchanged over nine years with the correspondent identified only as “A” in The Habit of Being and in the letters to her in Collected Works. In your book you identify “A” as Betty Hester, a young aspiring writer living in Atlanta. How close did O’Connor become with Betty Hester and why all the mystery surrounding their relationship?

O’Connor did find the daily mail “very eventful” as she spent so much time sequestered. Perhaps the most “eventful” of all was a fan letter she received from a young woman in Atlanta, Betty Hester, soon after the publication of A Good Man Is Hard to Find. Her great frustration was the incomprehension of her stories by many critics. When Hester wrote with the hunch that these stories were truly “about God,” O’Connor seized at the chance to correspond. Though only 87 miles apart, the two did not meet for over a year. Indeed the letters written before they met are often the most profound, as O’Connor chose to release to this well-read single woman her pent-up thoughts on art and religion, as well as piquant and often hilarious gossip about daily farm life.

Hester was assured of becoming a figure of fascination by Fitzgerald’s decision to protect her identity by giving her the moniker “A” in the published letters. She felt her mental state to be fragile and feared that journalists and scholars might descend. The mystery deepened when O’Connor’s 250 letters to Hester were sealed at Emory until 2007, and word leaked that Hester, who killed herself in 1999, had been bisexual and dishonorably discharged from the military. The letters opened up on my watch and rumors of an affair between the two appear unfounded. When Hester “came out” to her by mail, O’Connor was supportive but nearly blasé. More fraught was Hester’s decision to leave the church—having converted to Catholicism under her sway. O’Connor blamed the lapse on Hester’s new letter-writing crush, Iris Murdoch. “This conversion was achieved by Miss Iris Murdoch,” seethed O’Connor, as a weird epistolary battle ensued for Hester’s soul.

LOA: In her twenties O’Connor spent time at two writers’ havens: The Iowa Writers’ Workshop and Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, New York. What impact did the friendships she formed at these places have on her work? Who were her strongest influences?

Gooch: Tending to confuse O’Connor with the provincial characters in her stories, many are startled to find that she spent nearly six years living up North among the “interleckchuls.” Arguably the first great American writer to emerge from an M.F.A. program, O’Connor’s time at Iowa was transformative. The director Paul Engle encouraged her talent and helped her to get published in Accent and to receive a Rinehart fellowship to write Wise Blood, and he recommended her to Yaddo. While many fellow student writers—World War II vets on G.I. bills writing Hemingway-esque war stories—didn’t fathom her work, and gave her a hard time, Southern fiction was hot at the time. John Crowe Ransom, Robert Penn Warren—other Southern luminaries with three names—would come through the Workshop to speak and critique student work, and inevitably pick hers for special praise.

The surprise hero of my biography turned out to be Robert Lowell, palpably intense and brilliant in his sayings and doings. O’Connor first saw him speak at Iowa, and attended a dinner in his honor, but at her next stop, Yaddo, they became truly close. “He is one of the people I love,” she confided to Betty Hester. Lowell influenced her fiction, encouraging her to resist the commercial tailoring suggested by her Rinehart editors and instead to take the high road of art, exploring her dark religious vision. I can’t help but detect traces of Lowell—then in the midst of one of his antic episodes, and circling back into the church—in Haze Motes. Writing about a Christ-haunted character by day, she encountered one in Lowell nightly at dinner. Upon disrupting Yaddo by accusing its director of harboring communists, Lowell fled to Manhattan, with O’Connor and Elizabeth Hardwick trailing. But he made up for their exile by introducing O’Connor to friends crucial for her life and work: publisher Robert Giroux; and Robert and Sally Fitzgerald.

LOA: How did you first become involved with Flannery O’Connor’s work? Writing her biography must have immersed you deeply in her world. Did you discover anything about her during your research and writing that surprised you?

Gooch: I first became involved with O’Connor’s work by reading her stories in the late 1970s. She was my favorite fiction writer. The timing of this literary infatuation was lucky, as the first collection of her letters appeared in 1979. The connection between the fierce, funny stories with a strong spiritual undertow and the more humane and intellectually polymath woman of the letters fascinated me. I was seized with the bright idea that I like no one else should write her biography, even though I was a mere grad student at Columbia and had only published a chapbook of poems. Sally Fitzgerald responded to a letter I wrote pitching the idea by saying that she had been appointed authorized biographer. I waited for two decades for hers to appear. After she passed away in 2000, without completing a manuscript, I decided to become proactive and try my hand at it.

The great surprise was how much of a life O’Connor actually had and how much of that life was detectable in her work. She was not the Emily Dickinson of Milledgeville. O’Connor would write several letters daily to correspondents around the world. Most afternoons she received guests on her porch. As she had become something of a cult figure, cars would drive up, and sometimes they would contain the poet James Dickey, or the novelist John Hawkes, or Katherine Anne Porter, or Faulkner’s (and her) French translator Maurice-Edgar Coindreau. Likewise her work was full of inside jokes. She stole characters’ names, such as Tom T. Shiftlet, from the Milledgeville phonebook. Her mother, Regina, is a recurring caricature—often meeting a violent end. She took on topical headlines of the day: race relations in “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” religious themes inspired by Vatican II in “Parker’s Back.” I wrote another biography, City Poet, about Frank O’Hara, who described his poems as “deep gossip.” I was surprised at how much “deep gossip” occurs in O’Connor’s Grandma Moses acid visions, as well.

LOA: The sense I have from your book is that while O’Connor had strong feelings for several people in her life––John Sullivan, Robert Lowell, Robie Macauley, Erik Langkjaer, Maryat Lee, and Betty Hester––they were all platonic and none ever became what we would call “consummated.” Is that a fair reading?

I think “platonic” is a fair reading. The men with whom she was involved were generally intellectual big-brother types. They were also usually quite handsome, verging on “movie star” in the cases of Lowell and Lankgkjaer. And unavailable and safe: Sullivan was on his way to war; Macauley was engaged; Lowell involved with Elizabeth Hardwick; and Langkjaer, though unawares to her, heading off to become engaged to a Danish actress. Not to get too Freudian, but her relationships with these men were reminiscent of her father, who was likewise handsome and unconditionally supportive of her creative gifts. Hester and Lee were actively bisexual, and wound up “the more loving” ones. O’Connor tried to spin their love as spiritual, a maneuver that caused the more forward Maryat Lee to briefly pull back and accuse her of being full of pious clichés, not flesh and blood.

Funnily enough, when I wrote a biography of the flamboyantly gay poet Frank O’Hara, I got some flack for concentrating too much on his sex life and drinking. The argument, at least in 1993, was that he should be presented more as the “universal” poet he was, rather than so overtly “gay.” With O’Connor, I experienced almost the opposite: disappointment that salacious indiscretion was lacking. She did live with a fatal disease for most of her adult life. But I also think we might just need to accept that sexuality was not a driving force in her life, as perhaps it isn’t in many people’s lives. She also was not kidding when she said that Wise Blood was written by an author for whom belief in Christ was “a matter of life and death.” The spiritual orientation in O’Connor’s romantic life has turned out to be even more cutting-edge than sexuality—the next frontier, perhaps.