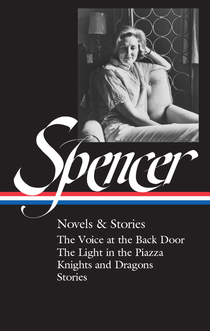

Major works:

The Voice at the Back Door • The Light in the Piazza • Knights and Dragons • “A Southern Landscape” • “On the Hill” • “The Wedding Visitor”

“On the page, Spencer makes what’s technically difficult seem unusually clear, then psychologically inevitable. From the start, her voice was praised for its tonal nuance, its stratospheric empathy. Spencer had the gift for infusing social situations with a bullfight’s fatality. . . . Spencer’s fiction reveals a trenchant eye for what’s questing and ludicrous and therefore fully human. She has the keenest ear for all that people try to say but rarely speak aloud. She proved herself an indispensable witness to the difficulties of having a home and then leaving it, to the struggles of smart, sexually alive young women trying to find their way in the world.”

—Allan Gurganus, The Paris Review

A Southern Landscape

Elizabeth SpencerWindsor is this big colonial mansion built back before the Civil War. It burned down during the eighteen-nineties sometime, but there were still twenty-five or more Corinthian columns, standing on a big open space of ground that is a pasture now, with cows and mules and calves grazing in it. The columns are enormously high and you can see some of the iron-grillwork railing for the second-story gallery clinging halfway up. Vines cling to the fluted white plaster surfaces, and in some places the plaster has crumbled away, showing the brick underneath. Little trees grow up out of the tops of columns, and chickens have their dust holes among the rubble. Just down the fall of the ground beyond the ruin, there are some Negro houses. A path goes down to them.

It is this ignorant way that the hand of Nature creeps back over Windsor that makes me afraid. I’d rather there’d be ghosts there, but there aren’t. Just some old story about lost jewelry that every once in a while sends somebody poking around in all the trash. Still, it is magnificent, and people have compared it to the Parthenon and so on and so on, and even if it makes me feel this undertone of horror, I’m always ready to go and look at it again. When all of it was standing, back in the old days, it was higher even than the columns, and had a cupola, too. You could see the cupola from the river, they say, and the story went that Mark Twain used it to steer by. I’ve read that book since, Life on the Mississippi, and it seems he used everything else to steer by, too—crawfish mounds, old rowboats stuck in the mud, the tassels on somebody’s corn patch, and every stump and stob from New Orleans to Cairo, Illinois. But it does kind of connect you up with something to know that Windsor was there, too, like seeing the Presbyterian hand in the newspaper. Some people would say at this point, “Small world,” but it isn’t a small world. It’s an enormous world, bigger than you can imagine, but it’s all connected up. What Nature does to Windsor it does to everything, including you and me—there’s the horror.