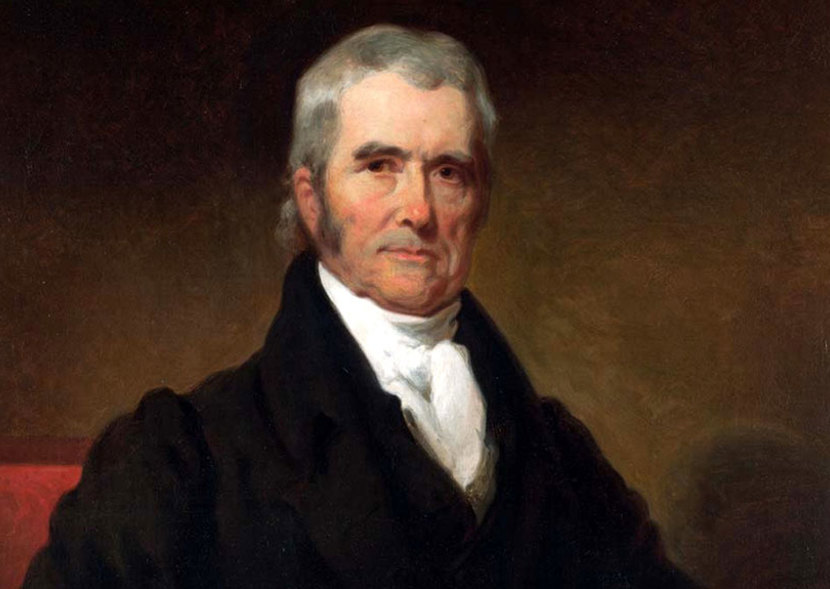

Marbury v. Madison (1803) • McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) • Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)

“[T]he most urbane and subtle mind of that era of remarkable statecraft. . . . Because of his shaping effect on the soft wax of the young republic, his historic importance is greater than that of all but two presidents—Washington and Lincoln. Without Marshall’s landmark opinions defining the national government’s powers, the government Washington founded might not have acquired competencies — and society might not have developed the economic sinews—sufficient to enable Lincoln to preserve the Union. “

—George F. Will

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

John MarshallIf any one proposition could command the universal assent of mankind, we might expect it would be this—that the government of the Union, though limited in its powers, is supreme within its sphere of action. This would seem to result necessarily from its nature. It is the government of all; its powers are delegated by all; it represents all, and acts for all. Though any one state may be willing to control its operations, no state is willing to allow others to control them. The nation, on those subjects on which it can act, must necessarily bind its component parts. But this question is not left to mere reason: the people have, in express terms, decided it, by saying, “this constitution, and the laws of the United States, which shall be made in pursuance thereof,” “shall be the supreme law of the land,” and by requiring that the members of the state legislatures, and the officers of the executive and judicial departments of the states shall take the oath of fidelity to it.