Major works:

“The Spinoza of Market Street” • “Gimpel the Fool” • The Magician of Lublin • A Crown of Feathers and Other Stories • A Day of Pleasure: Stories of a Boy Growing Up in Warsaw

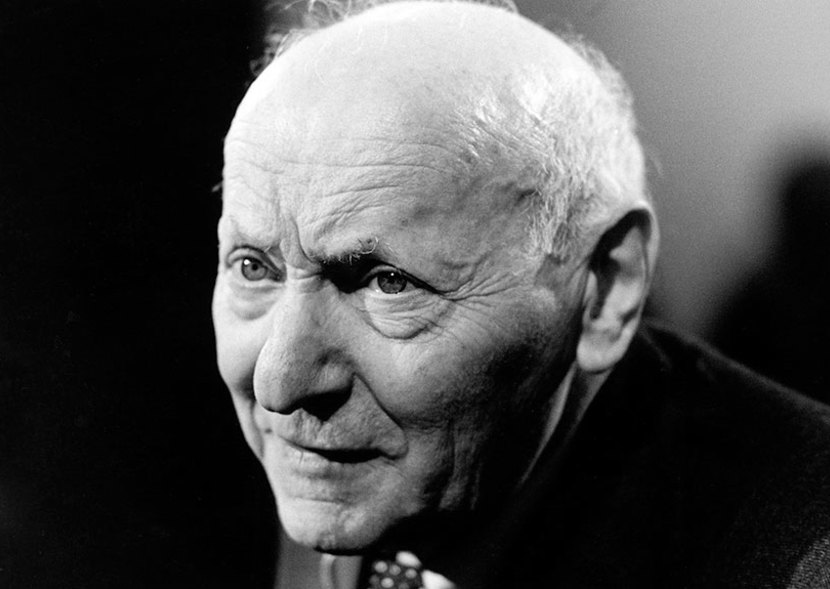

What makes a writer an American writer? The accident of his birth or perhaps the circumstances of his exile? His language? His themes? His audience? The works of Isaac Bashevis Singer, the seventh American citizen to be awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, raise these questions in fascinating ways. He was born in Poland and wrote virtually all his work in Yiddish, even after he immigrated to the United States in 1935 at the age of 30—yet he lived in New York City for more than 50 years and set many of his stories there. His writing drew on East European Jewish folk memory and mystical traditions, and on a shtetl culture that was worlds away from the glare and blare of postwar America. Yet the fictional world he created spoke movingly to the fears, longings, and ambivalence about assimilation of modern Americans. In his apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Singer conjured parables of Old World demons and holy fools. And his parables seemed, to his newfound American audience, startlingly apposite to the morally ambiguous world ushered in by World War II, even as they evoked, as in a dream, a time and a place the war had brutally obliterated.

“Singer’s stories have plots that unravel not because they are old-fashioned—they are mostly originals and have few recognizable modes other than their own—but because they contain the whole human world of affliction, error, quagmire, pain, calamity, catastrophe, woe: things happen; life is an ambush, a snare; one’s fate can never be predicted. His driven, mercurial processions of predicaments and transmogrifications are limitless, a cornucopia of invention.”

—Cynthia Ozick

A Day in Coney Island

Isaac Bashevis SingerI had been in America for eighteen months, but Coney Island still surprised me. The sun poured down like fire. From the beach came a roar even louder than the ocean. On the boardwalk, an Italian watermelon vender pounded on a sheet of tin with his knife and called for customers in a wild voice. Everyone bellowed in his own way: sellers of popcorn and hot dogs, ice cream and peanuts, cotton candy and corn on the cob. I passed a sideshow displaying a creature that was half woman, half fish; a wax museum with figures of Marie Antoinette, Buffalo Bill, and John Wilkes Booth; a store where a turbanned astrologer sat in the dark surrounded by maps and globes of the heavenly constellations, casting horoscopes. Pygmies danced in front of a little circus, their black faces painted white, all of them loosely bound with a long rope. A mechanical ape puffed its belly like a bellows and laughed with raucous laughter. Negro boys aimed guns at metal ducklings. A half-naked man with a black beard and hair to his shoulders hawked potions that strengthened the muscles, beautified the skin, and brought back lost potency. He tore heavy chains with his hands and bent coins between his fingers. A little farther along, a medium advertised that she was calling back spirits from the dead, prophesying the future, and giving advice on love and marriage. I had taken with me a copy of Payot’s The Education of the Will in Polish. This book, which taught how to overcome laziness and do systematic spiritual work, had become my second Bible. But I did the opposite of what the book preached. I wasted my days with dreams, worries, empty fantasies, and locked myself in affairs that had no future.