Nature & Environmental Writing

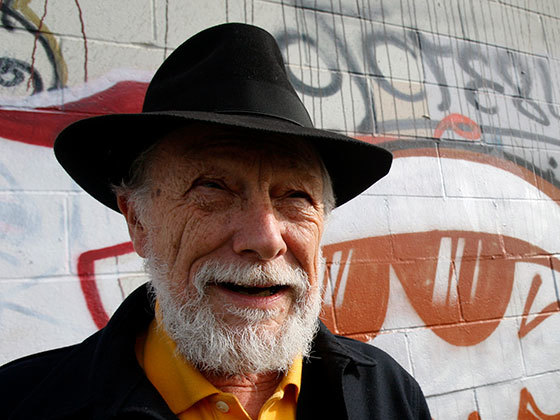

To read Loren Eiseley (1907–1977) is to renew a sense of wonder at the miracles and paradoxes of evolution and the ever-changing diversity of life. At the height of a distinguished career as a “bone-hunter” and paleontologist, Eiseley turned from fieldwork and scientific publication to the personal essay in six remarkable books that are masterpieces of prose style. Weaving together anecdote, philosophical reflection, and keen observation with the soul and skill of a poet, Eiseley offers a brilliant, companionable introduction to the sciences, paving the way for writers like Carl Sagan, Stephen Jay Gould, and Neil deGrasse Tyson. Now for the first time, the Library of America presents his landmark essay collections in a definitive two-volume set.

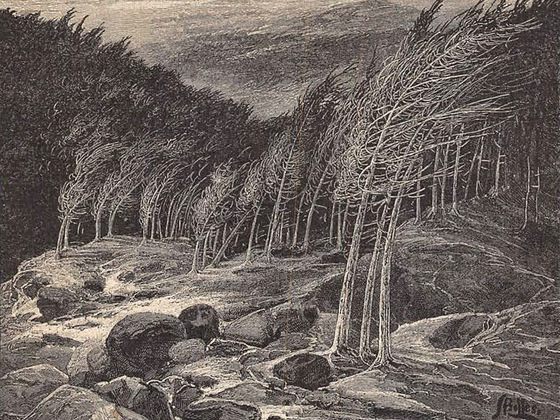

Beginning with the surprise million-copy seller The Immense Journey (1957), Eiseley produced an astonishing succession of books that won acclaim both as science and as art. Here, for the first time in a single collector’s edition, are all of Eiseley’s beloved, thought-provoking, sometimes darkly lyrical essay collections, from The Immense Journey to the posthumous The Star Thrower (1978). Eiseley’s subjects are wide-ranging, curious, and meticulously realized: the role of flowering plants in evolution; a disturbing insect, seen in childhood; the questions raised by a new fossil; a forgotten episode in the history of science. Beginning with close observation and vivid detail, Eiseley is fearless and imaginative in pursuit of the cosmological dimensions of the phenomena he describes.

William Cronon, editor, is America’s leading environmental historian. A winner of a MacArthur Fellowship, he is the author of Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (1983) and Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (1991), and he currently serves as Frederick Jackson Turner and Vilas Research Professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Each Library of America series volume is printed on acid-free paper and features Smyth-sewn binding, a full cloth cover, and a ribbon marker.

Project support for this volume was provided by The Gould Family Foundation.