Mystery & Crime

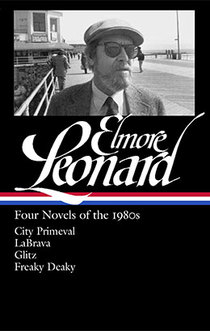

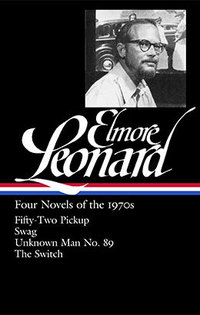

The latest Library of America volume, Elmore Leonard: Four Novels of the 1970s, recently arrived from the printer and will go on sale in bookstores everywhere this week.

We recently interviewed Gregg Sutter, who edited the volume. Sutter first met Leonard in 1979 and began working for him in 1981. He is currently at work on a biography of Leonard, from the unique perspective as his full-time researcher for more than thirty years.

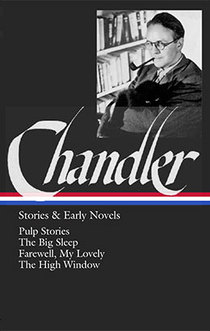

LOA: What was Elmore Leonard’s greatest contribution to the post-Chandler tradition of American crime fiction?

Sutter: Elmore did not come out of the Chandler tradition, which broadly includes the subgenres of detective, mystery, suspense, thriller, and crime fiction. Elmore’s writing school was Hemingway for the Westerns and George V. Higgins for the crime stories. He wrote dialogue-driven crime novels with an emphasis on character, from the point of view of both the good guys and the bad guys. Characters “auditioned” for their roles. If they couldn’t talk, they were in danger of getting bumped off. He frequently described the freedom he felt as a writer. “I make it up as I go along,” he said.

LOA: Who were the writers who influenced him?

Sutter: Ernest Hemingway had the most profound influence on Elmore. He studied Hemingway intensely when learning to write and well beyond, saying he always could pick up a Hemingway story and be inspired. But Hemingway lacked a sense of humor, according to Elmore. He found the natural humor he sought in the work of Richard Bissell. Finally, in the early 1970s, he read the work of Higgins, which had a liberating effect on his writing, especially showing Elmore how to tell a story with dialogue alone.

LOA: What did Leonard accomplish in his Detroit novels from the 1970s—and where did he go from there?

Sutter: With his body of work in the 1970s, especially the four novels included in the Library of America volume, Elmore began to be noticed in publishing and crime fiction circles as a rising star, even though he had been writing for thirty years. He also developed and refined a style that has been often imitated. Starting in 1981, Elmore set novels in South Florida, where his characters—often with a Detroit connection—migrated and found new opportunities, mainly criminal. These works did not go unnoticed. By mid-decade, he was recognized as one of the greats of contemporary American fiction.

LOA: As a Detroit native yourself, do you feel a special connection to these books?

Sutter: Absolutely. Detroit in the 60s into the 70s was known nationally for the auto industry, its sports teams, and Motown—and that was about it. I looked to New York and Los Angeles for cultural direction. By the mid-70s, it was Raymond Chandler’s Hollywood and Martin Scorsese’s New York that had my attention. Then in 1975, I read Fifty-Two Pickup by Elmore Leonard and that same devotion to place was bestowed on my hometown of Detroit, in novels, by an author who captured its sound and atmosphere.

LOA: You didn’t start working with him until the 1980s, but do you know of any anecdotes connected with the composition or reception of the four novels in the LOA collection?

Sutter: Before Fifty-Two Pickup, Elmore was best known for his westerns and his film work. Five of his previous six novels had been in paperback, which didn’t exactly raise his profile. But he was back in hardcover with Fifty-Two Pickup and soon discovered by The New York Times, which sang his praises, especially for Unknown Man No. 89. They said, “he can write circles around almost anybody active in the crime novel today.” The Switch, released in paperback, failed to receive the same critical attention as the others, but it was every bit as significant.

LOA: What were the high points and low points of working with Elmore Leonard?

Sutter: I’ll give an example of each. The low was when Elmore’s wife, Joan, died in 1993. She was his loving wife, smart friend and great editor. She was greatly missed, but Elmore quickly remarried and produced a string of great novels during the rest of the 1990s. The high points were the road trips with Dutch to exotic places like Cape Girardeau, Missouri, and Tishomingo, Mississippi. Hanging out with Dutch was always fun, and it brought me even closer to his work.

LOA: Do you see links between Leonard’s personal life and any of these four novels?

Sutter: Plenty. He weaves into all four novels elements of his personal life, such as alcoholism in Unknown Man No. 89, his background in advertising and the auto industry in Fifty-Two Pickup and Swag. Then, in The Switch, the contrast of the world of the country club party crowd in Detroit’s northern suburbs, with the bleak landscape of the city and its marginal inhabitants.

LOA: There was a scene deleted from Swag. Who cut it and why do you think it was cut?

Sutter: My feeling is that the scene, while entertaining to read, slowed down the fast-moving Swag a little, so the editor cut it. I’m not exactly sure who would have made the decision to cut it or Elmore’s reaction. In any event, it’s great that the deleted scene is included in the Notes for Elmore Leonard: Four Novels of the 1970s, so readers can enjoy this fun scene with Stick and Frank.

LOA: Did you make any personal discoveries or reassessments while preparing the LOA volume?

Sutter: My discoveries are just rediscoveries. Fifty-Two Pickup was the first Elmore Leonard novel I read. For me, it was the start a lifelong interest in his work as a fan and scholar. For Elmore, it was the beginning of a new phase in his career that would have glorious results. These Detroit novels have the same effect on me now as when I first read them in the 1970s, bringing forth a deep understanding of the landscape of Detroit, its sound and certainly its characters.

LOA: Do you have a favorite in the collection?

Sutter: That’s tough but if I had to pick one from the collection, it would be Unknown Man No. 89. This novel established Elmore as “a new and important writer,” as The New York Times put it in 1977. Its plot featured a shootout on Main St. in Rochester, Michigan, near where I had lived as a student. The unreality of Elmore’s fiction combined with the reality of my life, created a feeling of attachment with Elmore’s work that never left me.