Mystery & Crime

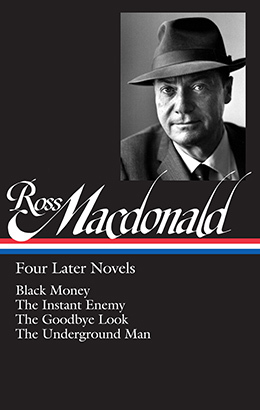

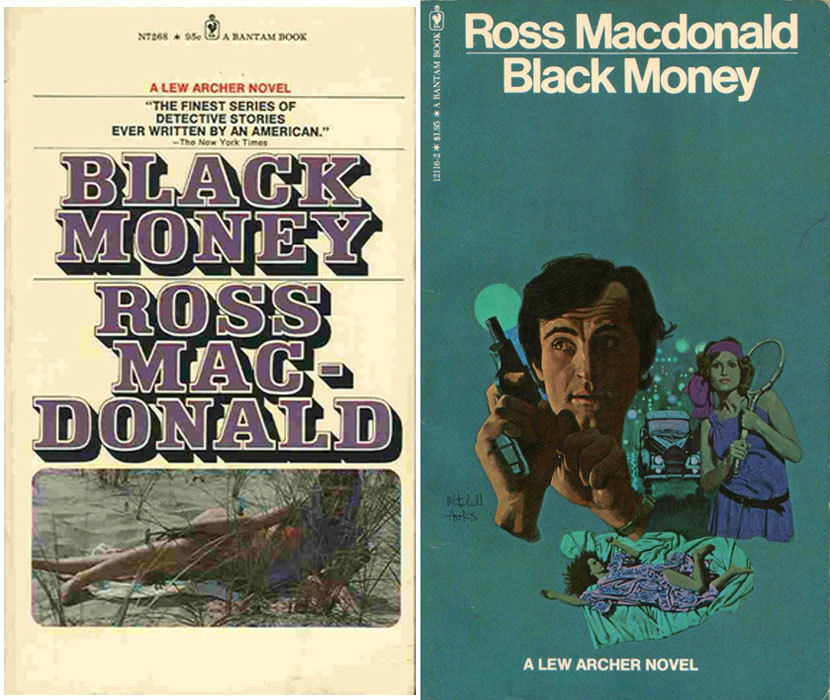

Released this week, Ross Macdonald: Four Later Novels is the third and final volume in LOA’s Ross Macdonald edition, bringing together four Lew Archer mysteries from the years 1966 to 1971. Below, editor Tom Nolan describes the welter of influences and unusually long gestation period behind the first novel in the collection, Black Money (1966).

Spoiler alert: Nolan’s essay reveals several critical details of the book’s plot. So if you haven’t already read Black Money, we recommend you do so right away and then come back and enjoy Nolan’s illuminating commentary on one of Macdonald’s most multilayered narratives.

By Tom Nolan

Silence, exile, and cunning: Irishman James Joyce’s motto would have made a plausible watch-phrase for Canadian-Californian author Ross Macdonald, too—a man so comfortable in the absence of speech that he often unsettled more compulsive talkers; a native of two countries who never felt quite at home in either; and a pseudonymous novelist who mulled and pondered each of his plots for years before committing one to paper.

Macdonald—real name, Kenneth Millar—had reached the summit of his art, if not of his career, when he wrote the consecutive quartet of books included in the Library of America’s new volume Four Later Novels, the first of which, Black Money, was the example par excellence of this writer’s patience and persistence in devising and refining an intricate and compelling plot over as long a period of time as he felt necessary.

“I think I had the central idea for Black Money in my mind for close to twenty years,” Macdonald later recalled. “It took me all that time to figure out how I could write it and to decide where the central character came from, who he was and what the source of the black money was. Year after year I would return to these ideas, make more notes and a cross-reference to [that old] notebook and put it away until I was ready. . . .” It was, he would guess in 1971, “the longest I have held a book in mind before I wrote it.”

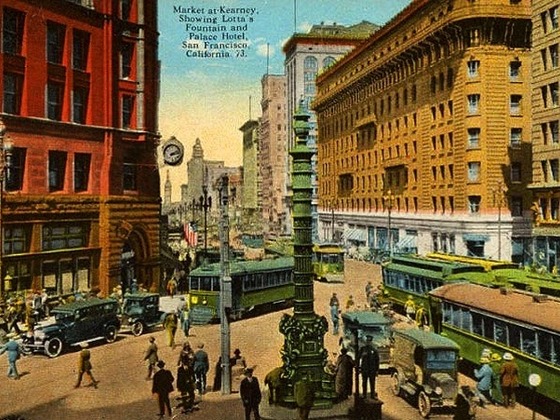

One of the things out of which Black Money grew was Macdonald’s sense of life in Panama, a country he visited in 1946 as an American Navy lieutenant j.g. en route to Boston through the Panama Canal. The fiction idea he started with, he’d say, was “the coming of a young Central American to the U.S. and his getting into severe trouble which ended in his death.” That notion haunted the author through a couple of decades, in-between the writing of several other books.

Also haunting Macdonald, through the gestation of Black Money and all his other works, was the memory of his own problematic childhood and adolescence in Canada. “I don’t write from life,” he insisted, “I don’t write about any actual person. . . . But when I write about Francis Martel in Black Money, a Panamanian boy who would seem at first glance to have nothing to do with me, I’m actually writing out of the shape of my own life. I’m writing about a boy who came up from nothing and had quite a career before his early death; this is the main difference from me: I haven’t died young!”

Elsewhere, he made the parallel more explicit: “Francis Martel in Black Money, like John Brown in The Galton Case, was suggested by my own experiences. Both Francis and John crossed a border, as I had, into the U.S., and attempted to start radically new lives in California. During this entire period, California has been the magnet among the States. . . . California was movie-land, where anything could happen.”

Back in the anti-magnet of his early hometown, Kitchener, Ontario, young Ken Millar’s maternal Mennonite grandmother had predicted this impoverished and virtually fatherless boy would come to a bad end. The grownup Macdonald spent the rest of his personal and professional life looking back over his shoulder at his vexed beginnings, seeking ways to alter or reinterpret his grandmother’s curse. “I always start with an idea . . . [which] contains in it the possibility of a strong reversal . . . ,” he said of his novels. “In Black Money, for example, Francis Martel appears as a . . . threat at first, but . . . turns out to be a victim. . . . The reversal is actually an illumination of what has gone before. . . .”

Another key element in the composition of Black Money was the 1925 F. Scott Fitzgerald work The Great Gatsby, which serves as a sort of phantom template for this and a few other Macdonald novels, especially The Galton Case.

“Yes, Gatsby hangs over my work,” Macdonald acknowledged to literary scholar Peter Wolfe, “its blessing and its curse, particularly over Black Money. But [that book is] saved for originality by embracing the Latin cultures, the U[niversity] culture, etc.”

Much of Black Money takes place among the residents of a college community—a mere two books after Macdonald’s masterly The Chill (1964), another novel with an academic setting. As informed a view of university life as that work had given, Macdonald’s English-poet friend Donald Davie had faulted The Chill for what he perceived as its somewhat dated feel: he thought the book drew on Millar’s recollections of his alma mater the University of Michigan in the 1940s and ’50s rather than detective Lew Archer’s present-day perceptions of a 1960s Southern California school.

Macdonald took such comments to heart. When his critic-friend Hugh Kenner suggested in the ’50s that first-person narrator Lew Archer was a bit too good a character to be true-to-life, the disgruntled author in time presented Kenner with the manuscript of a Macdonald novel which included a visit to a private detective (not Archer) much less forthright and compelling than his series hero: this, Macdonald claimed, was Archer seen from the outside. It’s possible Black Money’s contemporary campus setting was in part a response to Davie’s critique. Macdonald took pains this time to portray an up-to-date institution: he did research at another poet-friend Henri Coulette’s place of employment, L.A. State College.

His campus characters became crucial to the novel’s plot and mood. “[F]or the first time,” Macdonald told journalist Paul Nelson, “I was able to get a peculiar semi-tragic atmosphere about a kind of contemporary love affair which was fated—not really tragic; I mean the love affair between the professor and the girl. I was the witness of a love affair which resembled it in some ways, had been privy to what went on, and while I’m not writing about actual people, I tried to get the feeling of a fated and ultimately tragic contemporary love affair into my book. . . .

“[Black Money] seems to me to be the broadest expression of whatever sensibility I have, that I’ve written in a single book. . . . Sensibility is something I value, and I’m not always good at conveying it. But I felt the book came off, in a kind of original way, and had quite an original plot, in spite of its broad comparability to Gatsby.”

The novel’s working title was The Demon Lover, a name which made it all the way to the cover-page on the finished manuscript sent to Macdonald’s publisher. The text was full of the author’s characteristic dazzling imagery and astute insights into human behavior, all in service of the simultaneous unraveling of a present-day puzzle and tangled intrigues of the recent past. Despite his habitual protestations of never writing from real life, Macdonald was not averse to drawing emotional energy from events around him.

During a 1976 visit Paul Nelson made with singer-songwriter Warren Zevon and his wife Crystal to the Coral Casino beach club of which Millar and his author-wife Margaret were members, and which served as a fictional setting in many of their books, Macdonald told his guests, off the record, “that the love affair which took place in Black Money was actually happening at this club when he wrote the book,” Crystal Zevon said. “After he’d finished the book, there was a . . . death. . . . [One of the lovers] was found dead at the bottom of the steps along the beach.” “With his neck broken . . . ,” Warren Zevon added. “[T]here’s conjecture as to whether he might have fallen and broken his neck, but the implications are—”

The author found a more personal way to enliven his writing of Black Money. “That’s the one where he wrote in a black room,” Eudora Welty told an interviewer in 1990. “He showed me the house they’d lived in then, and he said he’d had everything made black: pulled the shades down . . . I don’t know why he did it, just for a lark, I guess—get him in the mood. . . . He liked to make a game of things. Sort of tease himself.”

Macdonald was pleased with the results of his months of writing and decades of planning. In February 1966, a month after the novel’s release, he wrote his publisher Alfred Knopf that Bennett Cerf (head of Random House, Margaret Millar’s publisher) had called recently “and said many people have told him Black Money’s my best book. This is my opinion, too.”

His opinion held firm. Three years later, regarding the contents of Knopf’s second proposed Archer anthology, Macdonald told editor Ash Green “I feel quite sure that Black Money is the book to go with Galton Case and Chill. They complement without repeating each other, go together like pieces of a puzzle, and constitute perhaps my most morally (and poetically) explosive books.”

In 1976, he told an interviewer from Gallery magazine: “Probably my strongest book is The Chill; it’s the one with the strongest plot. But personally I like the more recent ones better. I like Black Money.” He referred in a 1977 letter to Black Money as “my best style.”

But Macdonald was never one to rest on his laurels. As a professional writer, of course, producing a novel roughly every year, he could ill afford to. And with Black Money, his professional momentum had quickened: the book came out in coincidental tandem with the hit Paul Newman movie Harper, based on Macdonald’s 1949 novel The Moving Target; despite having the name of his private-eye hero changed (for contractual reasons), Macdonald’s public profile (and sales) had risen. In May of ’66, in a letter thanking publisher Knopf for a splashy Black Money advertisement in the New York Times, he wrote: “I think your ad is perfect, beautifully done and timed. Its effect on me was to make me want to get started on another book.”