Journalism

Published this month to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of American women winning the right to vote in August 1920, Library of America’s new anthology American Women’s Suffrage: Voices from the Long Struggle for the Vote 1776–1965 presents the definitive story of the campaign for women’s suffrage in this country.

Through one hundred selections curated and introduced by the collection’s editor, historian Susan Ware, the book relates the full history of the movement in all its diversity, with more familiar figures like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony joined by the African American, Chinese, and American Indian women who were not only essential to the movement but expanded its scope and ambitions.

Susan Ware is the author of Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote, American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction, and Letter to the World: Seven Women Who Shaped the American Century, among other books. She is Honorary Women’s Suffrage Centennial Historian at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, and General Editor of American National Biography. Her commentary is featured in The Vote, this year’s multipart PBS _American Experience documentary on the suffrage movement.

Via email, Ware explained the thinking that went into her selections and why this history is so germane to our current moment.

Library of America: This year we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, but in your introduction you’re careful to note, “the 1920 milestone had very little meaning for various groups of prospective female voters.” Who were those groups, and are they the reason why your anthology extends to 1965?

Susan Ware: Whenever we say “women won the right to vote in 1920” there should always be a mental asterisk next to that statement. Even though the Nineteenth Amendment said that the right to vote “shall not be denied on account of sex,” certain groups of women still found themselves unable to exercise that right. The largest group was African American women living in the South, who were subjected to the same Jim Crow restrictions like literacy tests and poll taxes that had been used to disenfranchise African American men since the late nineteenth century. It was the Voting Rights Act of 1965, rather than the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Nineteenth Amendments, that finally paved the way for Blacks to vote in the South, which is why the anthology uses that date as its end point.

Native American women also were initially left outside the Nineteenth Amendment until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 recognized their rights as U.S. citizens alongside tribal sovereignty. Puerto Rican women did not receive the right to vote until 1935, and Chinese American women not until 1943, when barriers to citizenship that dated to the 1880s were lifted as a wartime measure. In addition, numbers of women, especially Mexican American and Native American, bumped up against state restrictions that made it difficult for them to vote until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 removed those barriers.

LOA: In your introduction you write: “Fully telling the history of women’s suffrage means putting race at the center of the story.” How do the well-documented bigotry of certain prominent suffragists and the neglect of African American women’s contributions to the movement affect its legacy today?

Ware: Let’s start with the racism of prominent white suffrage leaders, who were often more than willing to pander to fears about Black women to advance their cause. Add to that their general unwillingness to welcome African American suffragists into predominantly white mainstream suffrage organizations, and you have a record of racism and bigotry that has to be recognized as part of the movement’s legacy. Not to excuse this behavior, but similar attitudes were likely found in almost any white-led movement back then. In other words, suffragists shared the attitudes of many white Americans at the time, rather than being unusually racist and intolerant.

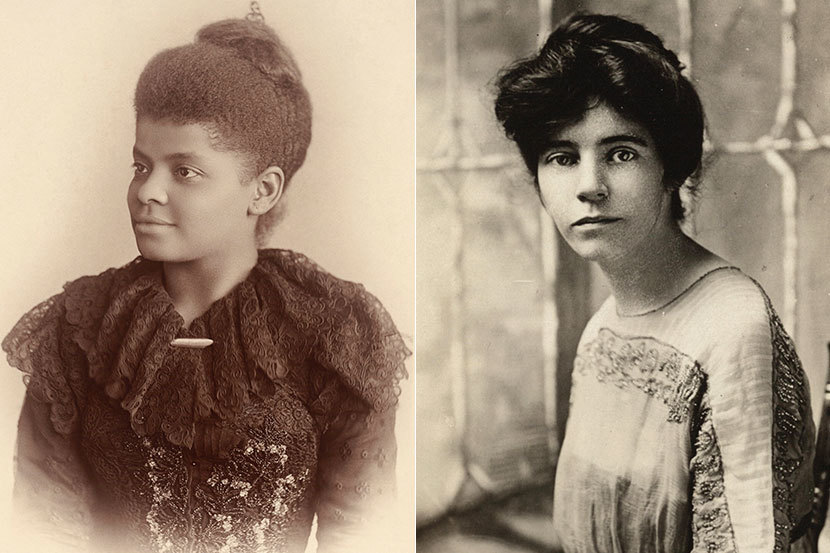

Because of this undeniable strand of racism, there is a tendency to dismiss women’s suffrage as a movement solely for the benefit of white, middle-class women, but this is shortsighted. Among other things, it continues the historical erasure of African American women’s vibrant contributions to the suffrage cause, which often occurred not within white organizations but in Black women’s clubs, churches, and community organizations. Because of what had happened to African American men’s voting rights after Reconstruction, African American women didn’t need to be schooled in the importance of the vote and they made its extension to women an important priority of their political activism. This story, which is well represented in the anthology, definitely deserves to be recognized as part of the larger suffrage history.

LOA: Your collection is also noteworthy for its regional emphases, highlighting the significance of events that took place in the West, Midwest, and even South. Why is it important to make sure these areas are included in the broader panorama?

Ware: For the simple reason that it is impossible to understand the suffrage battle, especially in its final decade, without paying attention to geography. The earliest victories were all in Western states; in contrast, many of the strongest suffrage holdouts were in the industrial Northeast and the South.

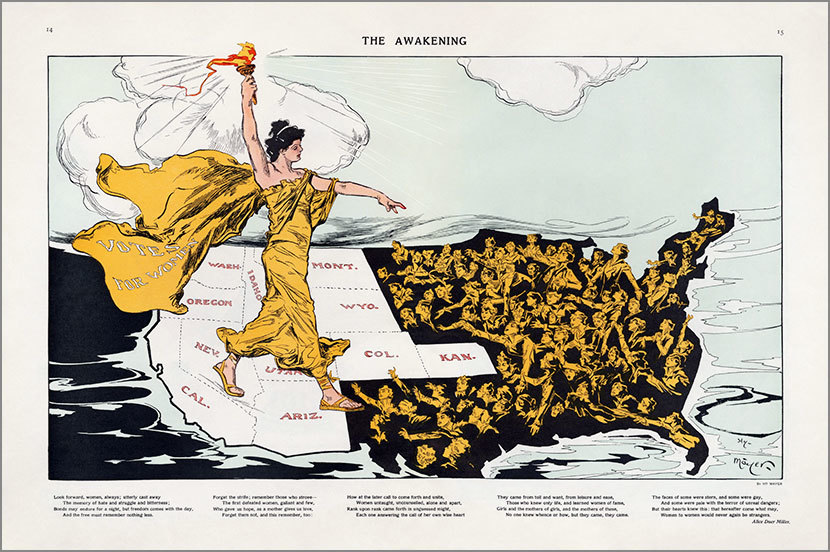

Geography matters: whether and when a woman first voted was very much shaped by where she lived. In particular the victories in the West, especially the successful California referendum in 1911, brought flocks of women voters to the polls years before the Nineteenth Amendment passed. Politicians took note of the increasing numbers of women voters; even if their states hadn’t yet granted women the vote, if and when they did, women voters might retaliate against politicians who had stood in the way. The successful 1917 women’s suffrage referendum in New York State was another regional victory with national implications, providing critical momentum in the final years of the struggle. And don’t forget that it was Tennessee, a Southern state, that put the Nineteenth Amendment over the top.

LOA: The Ida B. Wells piece included here, “Seeking the Negro Vote” (1914–1915), is a hardheaded account of the compromises, disillusionment, and disappointment attendant on real-world politicking. Was one of your aims to portray what can happen after a disenfranchised community gets the vote?

Ware: Advocating for the right to vote also meant advocating for larger roles in party politics, and party politics can be messy and complicated, as Ida Wells-Barnett found out in Chicago in 1914 and 1915. That was one reason for including the excerpt from her autobiography. The other was to reinforce the point that while the vast majority of African Americans still lived in the South, there were significant African American communities in Northern cities like New York, Pittsburgh, and Chicago, and those residents were deeply involved in politics on the local, state, and national levels, almost exclusively within the Republican Party. Not until the New Deal in the 1930s did African American voters switch their allegiance to the Democratic Party.

LOA: The barbed, witty poems of Alice Duer Miller are one of the most enjoyable discoveries in the book. Can you talk about some of the other more “literary” pieces—excerpts from novels and plays, for instance—readers will find in the collection?

Ware: Women’s suffrage was a political movement for a political goal, but suffragists also had a healthy sense of humor and a willingness to find creative ways to plead their cause. In their campaigns suffragists often resorted to humor and satire to make their points. Finley Peter Dunne’s clever dialogue with a millworker and Marie Jenney Howe’s monologue of rhyming couplets which punched holes in antisuffragist arguments are two examples. Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Hazel MacKaye realized that plays and pageants were a creative way to reach new audiences, and writers such as Mary Johnston and Oreola Williams Haskell also got into the act by writing suffrage-themed novels. And finally a personal favorite of mine: “How It Feels to be the Husband of a Suffragette,” published anonymously in Everybody’s Magazine in 1914 but now attributed to Arthur Raymond Brown, who was indeed married to a suffragist and wrote about their marriage with humor and panache.

LOA: The decade leading up to 1920 was marked by two rival approaches—that of the established “second-generation” suffragists and a younger, more militant group exemplified by figures like Alice Paul. You argue that it was the combination of both approaches that led to the Nineteenth Amendment’s passage. While we all know that history doesn’t repeat itself, is there a lesson here for activists in the twenty-first century?

Ware: Actually, in the case of suffrage, history was repeating itself, because the movement split after the Civil War over the question of whether newly freed African American men had priority over women, white and Black, in the provision of voting rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Like the split in the movement between Carrie Chapman Catt’s mainstream suffrage organization and Alice Paul’s upstart National Woman’s Party in the 1910s, the earlier split was over tactics and priorities, with personalities also playing a role.

The lessons from the suffrage movement for contemporary activists go beyond just accommodating rival approaches. They include a focus on electoral politics, lobbying and grassroots organizing to go along with mass marches and public demonstrations; the creative use of popular culture and new forms of media to get the word out; and the creation of coalitions and alliances that cross race, class, and other identities while drawing on the energies of multiple, overlapping generations. All of these themes are well represented in this anthology and are just as relevant today as they were at the height of suffrage mobilization.