Journalism

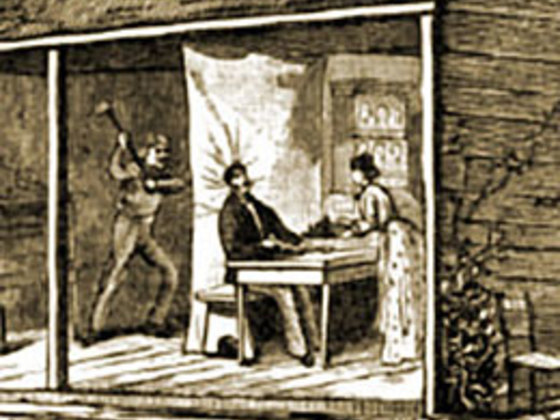

Here for the first time is the definitive story of the movement for women’s right to vote in all its diversity, told by the women and men who lived it. The voices of legendary figures in the suffrage struggle like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucy Stone join those of black, Chinese, and American Indian women and men who expanded its directions and aims, as well as anti-suffragists worried about where universal suffrage might lead the country.

Expertly curated and introduced by scholar Susan Ware, 90 pieces by over 70 writers tell the full history of the movement—from Abigail Adams in 1776, urging that the Continental Congress attend to women’s political and economic rights, to the Declaration of Sentiments in 1848 that took up that call again; from the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 to passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, which finally ended the Jim Crow era disenfranchisement of black women and men in the South. Here are Maria W. Stewart, Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, Mabel Lee, Constance Baker Motley, and many more arguing for suffrage for women and men of all races; presidents Grover Cleveland writing an anti-suffrage editorial and Woodrow Wilson urging passage of the Nineteenth Amendment as a wartime measure; Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s groundbreaking suffragist play; and stinging satire by Marie Jenney Howe and Alice Duer Miller. Here too are the women who campaigned against suffrage, as well as the women who picketed, marched, and were arrested for their belief that the right to vote is the heart of citizenship. Braided together into one coherent narrative, the writings gathered in this collection chart as never before the tumultuous course of early feminist activism in America.

American Women’s Suffrage includes an introduction, headnotes, explanatory endnotes, and an index, as well as sixteen pages of full-color illustrations and photographs.

Susan Ware is a celebrated feminist historian and biographer, the author of Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote, American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction, and Letter to the World: Seven Women Who Shaped the American Century, among other books. She is Honorary Women’s Suffrage Centennial Historian at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, and General Editor of American National Biography. Her commentary is featured in The Vote, the multipart PBS American Experience documentary on the suffrage movement.

This Library of America series edition is printed on acid-free paper and features Smyth-sewn binding, a full cloth cover, and a ribbon marker.

This volume is available for adoption in the Guardian of American Letters Fund.