Fantasy / Science Fiction / Horror

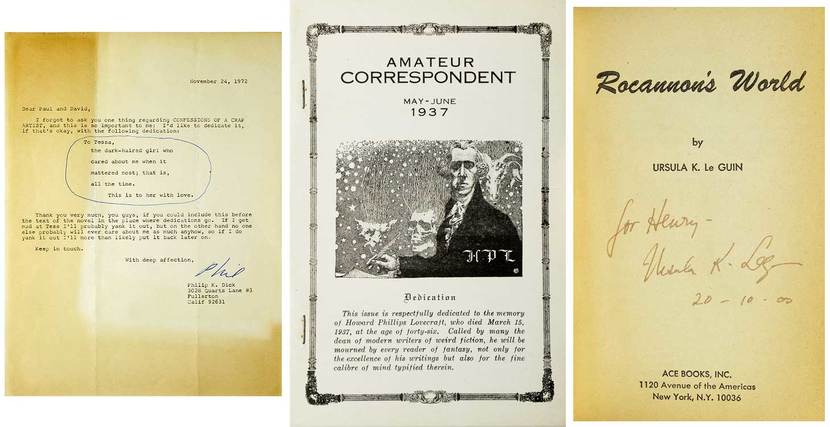

The fascinating exhibition A Conversation Larger than the Universe (currently in New York at the Grolier Club) showcases seventy books, magazines, manuscripts and typescripts, letters, and works of art from the collection of writer and antiquarian book dealer Henry Wessells. Stretching from the 1700s to 2017, the exhibition is a personal, idiosyncratic survey of the “fantastic” field from its origins in eighteenth-century Gothic all the way up to late-twentieth-century cyberpunk and the dystopian fictions of our present moment. Acknowledged masters like Ursula K. Le Guin, Samuel R. Delany, and Lord Dunsany appear alongside a host of lesser-known names, and fine-press limited editions are presented next to vintage paperbacks and pulps, like the August 1948 issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine that featured the first appearance of a Jorge Luis Borges story in English.

Below, Wessells continues his Conversation in an email interview with Library of America.

(All titles pictured below from the collection of Henry Wessells.)

Library of America: From the exhibition and its catalogue, we have the impression that for you science fiction is all but inseparable from a larger category, “the fantastic,” which can include not only fantasy and horror but such seeming outliers as Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys. How did you arrive at such an inclusive understanding of the genre?

Henry Wessells: I use the terms “science fiction” and “the literature of the fantastic” more or less interchangeably to refer to a mode of writing (and reading). Science fiction, fantasy, and horror are often viewed as distinct forms (largely for marketing purposes), but all three have their roots in the Gothic and share a common approach: to make the reader experience realities other than our ordinary reality. Science fiction, like rock ’n’ roll, is a form capable of integrating all influences while still remaining unmistakably itself. Rock ’n’ roll, like science fiction, is open to newcomers. The vocabulary can be learned and is an endlessly resilient process of discovery. Both forms are very slippery of definition but are instantly recognizable. Science fiction is notably resistant: the moment you try to pin it down, you can easily find work that violates or resists specific criteria.

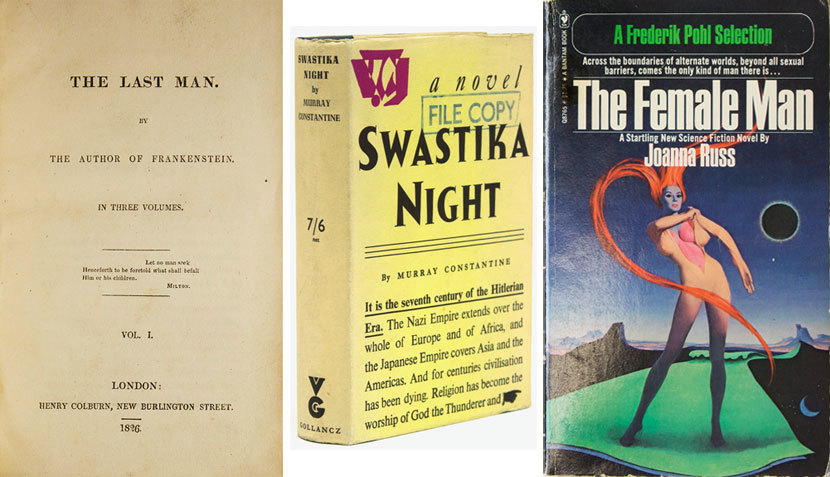

To retrace my path to Wide Sargasso Sea, consider how science fiction makes use of history (past and future) as the raw material of story—the brilliant critic John Clute describes how in the late eighteenth century, reality “became suddenly malleable”—and by the 1930s, when Winston S. Churchill can write “If Lee Had Not Won the Battle of Gettysburg,” history begins to seem equally plastic. And with Borges—whom science fiction can claim as “one of us” as forcefully as more mainstream literature—literature itself is an entire universe to be shaped. Something else is at work in Borges and Rhys than mere pastiche: the work of art as a critical commentary on an earlier work.

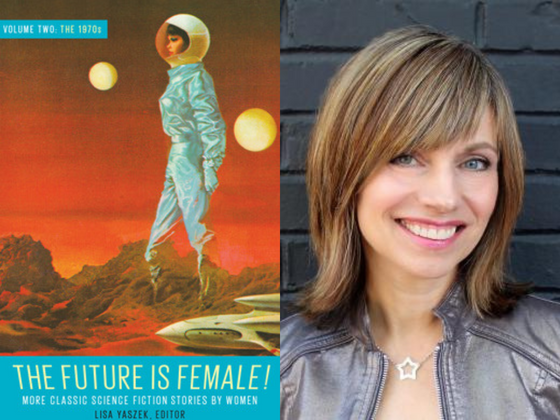

LOA: This year we celebrate the 200th anniversary of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. From Shelley through Ursula K. Le Guin and Joanna Russ to Karen Joy Fowler and Kelly Link, women writers are a notable through-line of the exhibition. Have women’s contributions traditionally been overlooked in considerations of science fiction and the fantastic?

Wessells: Women writers have been central to the fantastic, from the beginning, but their work has sometimes been greeted with hostility—this did not happen only in the fantastic. Science fiction may once have been a boy’s club, and certainly author and anthologist Judy Merril encountered deep resentment in the 1940s and 1950s. Things have changed, and contemporary science fiction includes remarkable work by women.

I credit Wendy Walker, author of The Secret Service (1992), the great underrated book of the 1990s, with making me more attentive to writing by women authors and to related political issues. The Gothic novels of the late eighteenth century dramatized real terrors of sexual and racial exploitation, and science fiction has explored these themes. Katharine Burdekin’s novel Swastika Night (1937), published under a male pseudonym, is a nightmare vision of a world where Hitler triumphed. Burdekin observed the realities of Nazi rhetoric, behavior, and politics to describe that world. Joanna Russ was a great critic and author whose women protagonists had interplanetary adventures like the men of the pulp years. Russ subjected science fiction to a clear-eyed literary scrutiny (she hailed G. B. Shaw and Virginia Woolf as her models).

LOA: A Conversation larger than the Universe is as noteworthy for some of the writers it leaves out—Ray Bradbury, Robert Heinlein, and J.R.R. Tolkien, for instance—as for the ones it includes. Is the canon due for a reassessment?

Wessells: This exhibition is drawn entirely from my own personal collection. The simplest reason for the omissions you observe is that I had neither the inclination nor the means to collect some of the authors whom I read in my early years. As a teenager, I read Jules Verne in French paperbacks of the 1970s, and those are scattered to the winds.

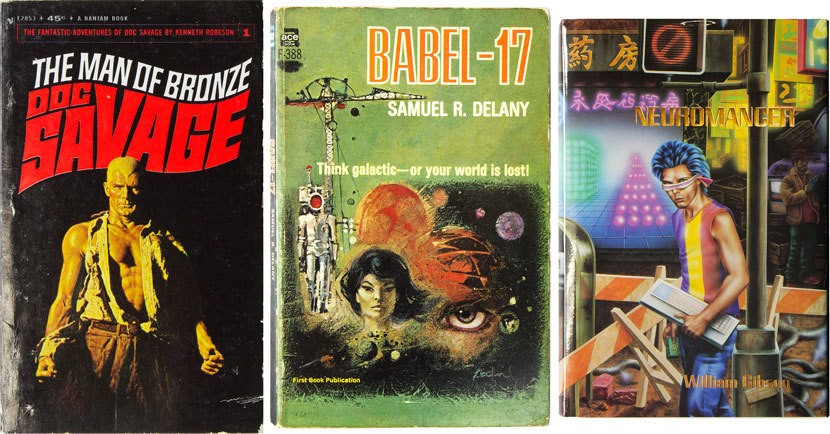

The canon is always due for a reassessment. Nothing is so remarkable as the changes that have occurred in science fiction from the early 1960s on, when the Anglo-American New Wave actively reshaped the science fiction field in terms of literary concerns, feminism, and the quality of writing. This accelerated after the retirement of “golden age” editor John W. Campbell and the rise of new generations of editors, such as Terry Carr, Gardner Dozois, Ellen Datlow, and David G. Hartwell. William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) took the world of science fiction by storm.

My interests as a reader have often led me away from the canonical texts of science fiction to the edges where something happens, where distinctions are sharpest, where the fantastic is not so much a place you get to as it is the way you went.

LOA: The Grolier Club exhibition is a fascinating assemblage of literary materials—antiquarian books, pulps and paperbacks from the mid-twentieth century, typescripts and personal correspondence, even a photocopy of a 1996 fax from William Gibson. How did you begin collecting, and what criteria do you use in evaluating a potential new acquisition?

Wessells: I started reading the Bantam paperback reissues of the Doc Savage pulp novels when I was seven years old, and read widely in science fiction and fantasy into my mid-teens. But it was the simultaneous discovery of Brian Eno’s album Another Green World and the sharp satire of Robert Sheckley that kept me into a reader of science fiction as an adult. I bought the Eno/Sheckley multimedia album In a Land of Clear Colors when it appeared, and the signed edition of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home not long after publication. Years later, encountering the work of Avram Davidson (another writer who defies categories) led me to look for more of his writings. I became his posthumous bibliographer and editor, and began to write and publish essays, poetry, and fiction. This collection grew from that activity.

The books on my shelves are often books I write about, or intend to write about, or are books written by friends. I am interested in understanding the original context in which a book was published, and in the connections between books and their authors and their lives. As a collector and as a writer, I am interested in association copies, books that document ties of friendship. As Robert Irwin writes of scholars in a different field, in Dangerous Knowledge: “In their minds, they walked and talked with dead men.”

We live in a small house, so as a collector I am constrained by space. A single book is sometimes enough to represent an author or aspect of science fiction—that is as a collector, only, for as a reader one must not neglect the lesser-known books and authors.

***

Anyone in the greater New York area with even a passing interest in science fiction and fantasy is urged to visit the Grolier Club for the final days of A Conversation Larger than the Universe, on view through Saturday, March 10. The lavishly illustrated catalogue accompanying the exhibition, also published by the Grolier Club, is equally recommended. Much more than a checklist of the items on view, the book is a series of informative and gracefully written essays in which Wessells delves into the history of these works and argues for their significance.

Henry Wessells will moderate a panel discussion on science fiction at the Grolier Club on Tuesday March 6, 2018, from 6:00 to 7:30 pm. Panelists slated to appear include Christopher Brown, Siobhan Carroll, John Crowley, Ellen Datlow, Samuel R. Delany, and Maria Headley.