Fantasy / Science Fiction / Horror

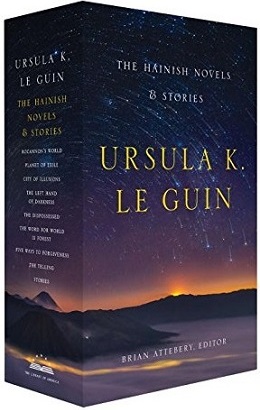

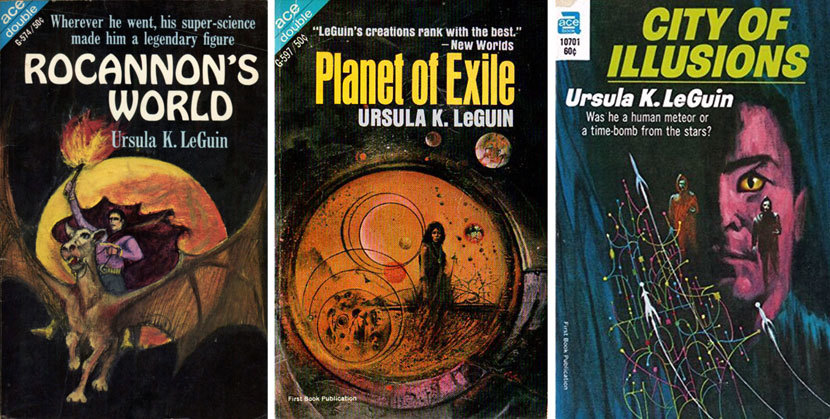

Library of America’s Ursula K. Le Guin edition continues this fall with the release of The Hainish Novels & Stories, a two-volume set of works that radically expanded the possibilities of science fiction from when they first started appearing in the mid–1960s—and that inspire fervent devotion and debate to this day.

Since we don’t often have the opportunity to interview one of our authors about her work, it’s a special privilege to offer the following Q&A. Le Guin responded to our questions via email from her longtime home in Portland, Oregon.

LOA: The Hainish Novels & Stories collects, for the first time, a large body of novels and short stories that appeared separately over more than thirty years. How is the work altered, and what does it gain, from being presented complete?

Le Guin: Putting them all into one (very handsome!) box won’t alter the stories and novels. But seeing them all together, readers inevitably will perceive them differently, and may expect them to form a coherent pattern, to be parts of a single history, all proceeding in the direction of time’s arrow.

But they didn’t all grow from a single root and follow a single story, as my books and tales of Earthsea did, like a big tree slowly growing. This collection is more like a forest than a tree. There are all kinds of of trees in it, and various paths through it, all following different directions, some rejoining other paths, some of them going nowhere but farther in the forest. . .

But there are of course links among the books and stories, and the links grow stronger through the years I wrote them. Seeing them all together may make those links clearer.

LOA: Brian Attebery, editor of the collection, suggests that “readers emerge from these planetary expeditions with vision refreshed and courage reinforced.” Why might that be the case, when straightforward “happy” endings are so rare in these works?

Le Guin: Are there entirely straightforward happy endings outside fairy tales? A story that begins “Once upon a time”—that is, outside time—can end, with absolute honesty and truth, “So they lived happily ever after.” But in reality it seems that the best we can do in a lifetime is to live as well as we can, experiencing much grief, pain, and happiness, till we die. So a story set in the “real world” can’t promise anything forever after. But it can offer hope.

Science fiction imagines other places, other times, other beings and ways of being, by using the tools of realism and working almost entirely within its limits. Its unique quality as fiction lies where it breaks through those limits into pure imagining; but the limitations are part of its strength.

The stories in this collection are science fiction, not fantasy. They take place far from the borders of Elfland, in worlds like ours, where there is no perfect happiness. We need to imagine leading a better, wise, happier life than we do—but we need just as much to know that it will never be easy and never be forever.

LOA: The Left Hand of Darkness is widely celebrated for its exploration of gender themes, of course, but it’s also a thrilling adventure story. What kind of research went into making the protagonists’ long, grueling flight across the ice so believable?

Le Guin: I’d be ashamed to call it most of it research. I got fascinated by the history of early Antarctic exploration and the writings of Scott, Shackleton, Cherry-Garrard, and all the men who headed for the South Pole on foot, hauling their supplies, because they had no other way to do it. I read these grueling adventures for the sheer pleasure of it, because I loved them—the best possible way to acquire knowledge about anything.

When the novel began to take shape in my head, the world Gethen—a world in an Ice Age—needed a lot of planning. I did go the library and read up on how the Northern Finns get through the winter, and so on. And I had to plan out the trek across the Gobrin Ice just as carefully as Estraven did, ounce by ounce and day by day.

But once I had all that in notes or in my head, I could just turn the two of them loose and find out what happened.

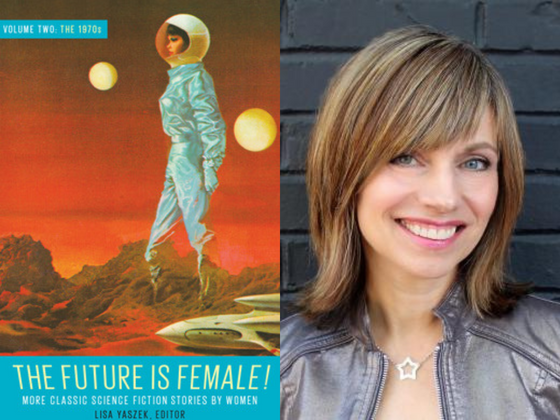

LOA: In your introduction to Volume Two, you mention a period of “hard study” between the earlier Hainish works (from the 1960s–70s) and the later ones (from the 90s), during which you rethought your understanding of sexuality and gender. What did that study consist of—and when did you know you were ready to revisit the Hainish universe?

Le Guin: Well, that study took a lot of reading the literature of modern feminism, which was in full flood by then, and discovering earlier writing by women that I’d neglected or not known because literature had been purified of it by the academic and critical filters (“standards of excellence”) established by male supremacism. It took hard thinking about myself and who I was, what it meant to write as a woman, and why it was so scary to try. It took hard work to free my work from the dominance of male experience, interests, values so that it could make better sense about human experience, interests, and values.

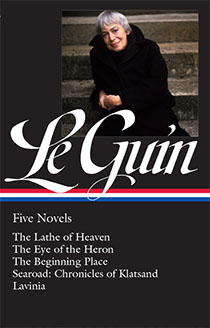

Because SF had been so very male-dominated, I thought for a while that I might not be able to write it any more; but that was just cowardice. I began to find my way with the short novel The Eye of the Heron, and from there back to the Hainish worlds.

LOA: When the Times Literary Supplement reviewed The Telling just weeks after 9/11, the reviewer called it “shockingly prescient” and singled out this sentence: “Secular terrorists or holy terrorists, what difference?” Would you care to comment, from the perspective of 2017?

Le Guin: Was I prescient? Or was I just looking at what Mao had done in the “Great Leap Forward,” and at what sects and governments were doing all over the world in 2000 and 2001? Because it was so terrifying, I wanted to try and say Let’s not go on this way!

Sixteen years later, looking at Guantánamo, Islamic terrorism, Myanmar, what can I say?

LOA: A notable through line in the Hainish stories is your lifelong interest in traditional Asian creeds and cultures (Taoism most famously). Can you describe how that interest inspires you imaginatively, and how you work with it in writing fiction?

Le Guin: I’ve tried many times to answer this question, but my answers always feel evasive and superficial to me.

Maybe the answer to the question “why and how do the Taoist and Buddhist views of the world inspire you with thoughts and imaginations?” lies not in anything I can say about these ancient, complex, profound ideas and beliefs, but in the works they have inspired me to write.

Better yet, I’ll just leave it to Lao Tzu:

_The way you can go isn’t the real way.

The name you can say isn’t the real name._