Fantasy / Science Fiction / Horror

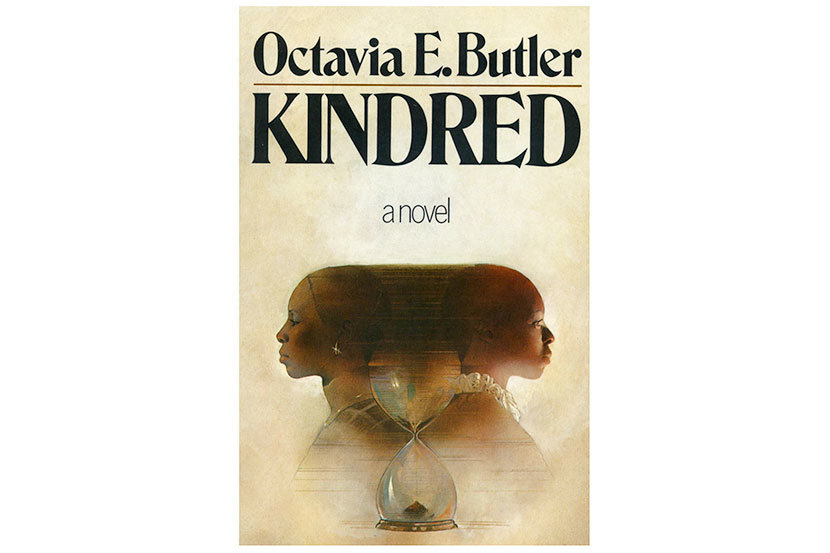

Library of America extends its commitment to the best, most groundbreaking works of American science fiction with the release of Octavia E. Butler: Kindred, Fledgling, Collected Stories—the first volume in the projected complete works of a writer whose impact and influence on the genre can rightly be called transformative.

Edited by two authorities on Butler’s writing, Nisi Shawl and Gerry Canavan, the book has already attracted attention from the New Yorker, the London Review of Books and Bookforum, where Gabrielle Bellot writes that LOA’s inaugural Butler volume allows “both fans of Butler and those unfamiliar with her work to gain an impressively broad view of her oeuvre.”

Nisi Shawl is the author of the story collection Filter House, winner of the 2009 Tiptree/Otherwise Award, and the novel Everfair, a 2016 Nebula finalist. She edited Bloodchildren: Stories by the Octavia E. Butler Scholars (2013) and coedited Strange Matings: Science Fiction, Feminism, African American Voices, and Octavia E. Butler (2013). Shawl is also a founder of the diversity-in-speculative-fiction nonprofit the Carl Brandon Society and serves on the Board of Directors of the Clarion West Writers’ Workshop.

Gerry Canavan is an associate professor in the English Department at Marquette University, specializing in twentieth- and twenty-first-century literature. An editor at Extrapolation and Science Fiction Film and Television, he has also coedited Green Planets: Ecology and Science Fiction (2014), The Cambridge Companion to American Science Fiction (2015), and The Cambridge History of Science Fiction (2019). His monograph on Octavia E. Butler appeared in 2016 in the Modern Masters of Science Fiction series at University of Illinois Press.

Via email, Shawl and Canavan discussed the writings collected in the new LOA volume and what makes Butler’s work so distinctive overall.

Library of America: Beginning with her debut, Patternmaster, in 1976, Octavia E. Butler (1947–2006) published twelve novels and one short story collection that were marketed as science fiction. In the wake of this large body of work, how does the genre look different from how it did before her arrival?

Nisi Shawl: It looks bolder. It looks both more nuanced and less compromising, because Octavia’s take on the genre’s concerns—what makes us human, how we survive into the future, what we’re living for—was always nuanced at its heart and yet unflinching in its examination of unpleasant truths.

I also believe that much of the genre’s increasing inclusivity is due to Octavia’s presence. By modeling the creation of imaginary worlds in which she and those like her—and those unlike her yet also unlike the dominant definition of “normal”—took part, Octavia influenced a myriad of other creators. Some of us belong to non-dominant demographic groups; all of us are interested in portraying non-dominant groups and group members in our work, as she did.

Gerry Canavan: As she herself said, “she wrote herself in.” She was part of a moment in the genre that made an earlier era of science fiction that was clustered around white men seem not only old-fashioned but ridiculous—and many of the writers that have come after her, like Nisi herself, have looked to her as a forerunner and as inspiration, even as they’ve taken the genre down their own new paths.

LOA: Nisi, in your introduction to the new LOA volume you write, “The disquiet Octavia’s stories elicit is far from gratuitous. It is intrinsic to her work.” That assertion might seem self-evident in a novel centered on slavery, like Kindred, but how does it play out in one like Fledgling, which she called her “fun” novel and is ostensibly a fantasy thriller about vampires?

Shawl: I have friends who refuse to read Fledgling. Yes, it’s a disquieting book—initially because of sexually active protagonist Shori’s pre-pubescent appearance, then because of the power dynamics at play between the vampires and their human “families.” And the novel’s disquiet doesn’t stop there—but I will, for fear of spoiling the experience for new readers.

Octavia’s writing is fun. But it’s not the kind of fun that makes you feel all cozy and comfortable when you read it. It’s not like eating meatloaf. It’s more like skydiving: exhilarating, risky, life-changing. Liberating. You can be quiet or you can be thrilled, satisfied with the status quo or questioning it.

Canavan: When I’ve taught Fledgling, I’ve had students adore it and had students find it so disturbing they almost couldn’t go on with the reading. Even though it is couched in the fantastic, and silly stuff about space vampires, what Fledgling does with and to sex has roots in real-world relations of pleasure and domination. Part of the joy of Butler’s work, especially for people who didn’t always see themselves in that older-style science fiction, is in letting her female characters and her characters of color inhabit those morally grey areas that are often reserved for white male anti-heroes—that seems to be part of what she found so stirring about her own work—but all the same these stories go to some dark places where behavior can’t easily be classified as “good” or “bad.” There’s real danger in these stories.

LOA: It’s eye-opening to learn, from a 1998 interview, that in Kindred Butler actually exercised some restraint in her depiction of slavery because, as she put it, “You don’t really want to know the intimate details of what people had to go through, because they’re so ugly and awful.” What do we know about the research that went into Kindred, which is both a work of speculative fantasy and a kind of historical novel?

Shawl: Octavia approached her research on multiple fronts. She read: books, newspaper articles, letters, bills of sale. She theorized, she studied maps, she pored over floor plans. She visited a plantation in person, a visit which involved a long and (for her, at that time) horrendously expensive cross-country bus trip and hotel stay.

Afterwards, she was able to turn her memories of the research she did for Kindred into a series of semi-humorous anecdotes about dusty cigarette butts in her hotel room and so on, but I believe that journey was an enormous stretch for her, both financially and in terms of the numerous potential encounters with complete strangers. It must have taken great determination, and great dedication, and a firm belief in herself to go so far out of her comfort zone in pursuit of the goal of writing the best Kindred she could write.

Canavan: She would say later that as grim as Kindred is, it still doesn’t approach the real brutality of slavery, and that in some basic way it still let the reader off the hook of really confronting the nightmare. She believed a book that truly captured the full horror of slavery wouldn’t sell (she was always acutely aware that her books had to sell); there’s an inevitable softening that has to happen when the book has to be something people willingly buy, experience, and tell their friends about.

I think this is a pretty remarkable thing to think about, considering just how much violence and horror Kindred already contains.

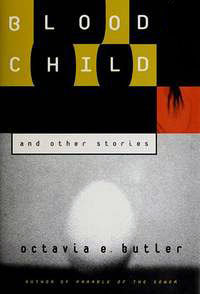

LOA: In an introduction to a collection of her short fiction included here, Butler confesses: “The truth is, I hate short story writing.” Yet in a thoughtful survey of Butler’s career in a recent London Review of Books, Jenny Turner argues that “it’s the tales that show her at her best.” What did the short story form allow Butler to do that she didn’t do in her longer works?

Shawl: I’m a bit unorthodox in my stance on the differences between short stories and novels. For one thing, I think that novels are much simpler in structure than short stories. There are these big, essential novel plots, and then novels’ subplots sort of dangle off of them like ornaments off a Christmas tree, but they’re not the basic thing itself. They’re dependent, but not really necessary. Whereas the plot threads of short stories are all tightly wound together, all related, and, when you lay them out separately, quite complex in how they connect with one another.

Anyway, here are a couple of things I believe Octavia got out of writing short stories: the opportunity, first, to experiment with an idea without lavishing months of time on it. And the prodding effect of a constraint, second, because often it helps to have boundaries to push against. In this instance the constraint is that of length.

Canavan: That’s so interesting. I’m not sure I’d agree that Butler is better in one form or another; I agree with Nisi that the different forms make different things possible for her. Her short stories, like most short stories, are intensely focused on particular moments in time; the novels get to tell stories that take place over months, years, or decades, and get to meander a bit more. I think what I would say is that the stories are much more specifically focused on particular sorts of problems, thought experiments, and play out to a solution; the novels are much more complex and ambiguous both in the narrative situation they describe and in the ultimate “solution” the text poses. That might make it easier for her short stories to circulate in anthologies; there’s a way in which they’re more digestible intellectually, and (frankly) upset the reader less.

I wouldn’t know how to choose between one or the other, though! Anything she wrote is worth reading.

LOA: In the absence of a full-scale Butler biography, did you feel a special sense of responsibility in preparing the chronology for the LOA edition? What were some noteworthy discoveries you made while researching it?

Shawl: This is definitely one for Gerry. I did get to review what he did, and that certainly evoked a special sense of responsibility in me. It gave me the courage to suggest a couple of changes, even.

Canavan: There is a good Butler biography we didn’t have access to when we were working on the chronology; Lynell George’s A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia Butler. I’d recommend it! We did work hard on the chronology, and while I was forbidden from thanking her in the text of book itself [LOA Associate Editor] Stefanie Peters did an amazing job guiding this process and helping me to make the chronology as terrific a testament to Butler’s life as it is. I was so glad to have her help in shaping it, as well as in encouraging me to dig deeper where we needed to.

I think some of the quotes we have in there from Butler’s unpublished autobiographies will be new to readers. We also wrestled with some of the details of her childhood that she talked about in different ways in different contexts and at different moments, regarding such things as the death of her father; we wanted as best as we could to recount accurately both what happened and how she felt about it later.

LOA: Butler’s engaging essays reveal her to be a practical, disciplined, highly professional working writer at the same time that she was a boundary-breaking pioneer. How open was she about her status as a vanguard Black writer—either in print or anywhere else?

Shawl: By the time I knew her—I’d met her earlier, but we really got to be friends in 1999, when she moved here to Seattle—Octavia had accepted her role as a pioneer. She knew she was a big deal. But she still behaved graciously, politely, and modestly, and she always seemed genuinely surprised to learn that someone she met had read her work. She understood what a difference she was making as a Black woman author, and she loved it. She wanted it. Shortly before her death, Octavia and I were discussing the Carl Brandon Society—that’s a nonprofit I helped found that supports the presence of People of Color in the genre. Not only was Octavia an early member and 100 percent behind the CBS mission, she was actively engaged in coming up with ways her status could assist the organization in fulfilling that mission. “Use me!” she told me, rather urgently. A year later we were administering a scholarship in her name.

The scholarship is great, and it has been a boon to a whole new generation of writers from marginalized communities—Indrapramit Das, Dennis Staples, Mimi Mondal, and many more. But how I wish we could have them and her too, still alive.

Canavan: I think that was a process for her; there was a time when she bristled at the idea of foregrounding her racial identity, especially early on, but as Nisi says she was acutely aware of just how much of a pioneer she was and what her work meant to the people who came later. Some of her best writing about this are the autobiographical essays in Bloodchild; she understood very well that what was unique about her story was not the obstacles that had been placed in her way but the combination of talent, hard work, luck, grit, and pure stubbornness that allowed her to break through despite them. And she was so generous in her efforts to lift up people in similar situations; it still floors me that she would let people she’d never met call her at her home to get writing advice or send detailed feedback to the unsolicited manuscripts she received in the mail. She was so giving. There’s a reason everyone who knew her loved her.