Wendell Berry in Henry County, KY, in the 1970s (James Baker Hall)

Across genre, whether in novels depicting the sweep of history in small-town Kentucky or nonfiction perorating on behalf of a renewed human relationship with the earth, Wendell Berry remains one of America’s most profound interpreters of place and people. A farmer-writer of uncommon moral clarity, he mixes a contrarian independence of mind with a rare capability to perceive the innumerable ties—environmental, familial, philosophical—that bind us to one another and to the planet. The author of more than fifty books, he is the namesake of the nonprofit Berry Center in New Castle, KY, and, in 2010, was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Obama.

To mark his ninetieth birthday this week, we reached out to a handful of his friends, fans, and collaborators—a mini-Membership of those touched by Berry’s wisdom and influence. The response was overwhelming: an outpouring of tributes and toasts testifying to his brilliance, heart, and artistry.

Read on for comments from star chefs, musicians, fellow authors, and others enriched by the legacy of this self-proclaimed Mad Farmer who, for more than half a century, has done so much to bring the American landscape—in all its dimensions—into focus.

Click the links below to jump to a specific contributor. A reflection from LOA associate editor Stefanie Peters on her work with Berry can be found on the Rabbit Room website.

Dr. Leah Bayens | Michele Guthrie | Jeff King | Bill McKibben | Dr. Russell Moore | Andrew Peterson | Luci Shaw | Jack Shoemaker | Jane Vandenburgh | Alice Waters | Dorothy Wickenden

When I first sat with Wendell to talk about educating farmers as farmers, he started by turning to the idea of love—in the fullness of the term, not sentimentalized but fully rounded, with the joyful and the difficult joined through membership in a place and with its people.

He then asked a question that I try to answer every day: what works does this love propose? An agrarian life of learning and teaching, of friendship and work, that grows from love is radical. It gets to the roots. It is a worthy starting point for all manner of concerns about culture and agriculture and for humbly abiding nature’s standard.

I’ll be spending the rest of my life responding to this question, in and out of class. I’m proud to do that with people drawn together at the Berry Center to do the next right thing in front of us every day.

Dr. Leah Bayens is Director of the Berry Center Farm and Forest Institute.

Wendell Berry continues to work, writing and speaking about agriculture, family farms and farmers, the importance of nature, precious small rural communities and peaceability. He believes that properly scaled farming is essential to healthy local economies and that healthy local economies are essential to the wellbeing of the country and the earth. He guides our work at the Berry Center often by his presence with us and always with his words.

Michele Guthrie is Archivist at the Archive of the Berry Center.

Berry in Henry County, KY, 1970s (James Baker Hall)

I come from a long line of city slickers, so my first encounter with Wendell Berry’s agrarian vision was a revelation. Could we farm too? Would we starve? There was a tantalizing impossibility to his thought that was nevertheless productive. In the end, we didn’t get the farm, but we did add some backyard chickens and several rabbits to our household. They’ve taught us about the rhythms of creation and place in many of the ways Berry told us they would. We probably should have called one of them Jayber.

My closest brush with Berry himself was a response I received after I wrote him a fan letter. I’d been reading his essays to procrastinate from my graduate studies. My penmanship wasn’t great, but I wanted Berry to know that his message was landing, so I wrote the letter by hand. In it, I shared some of the more esoteric concepts I’d come across that I thought resonated with his writing. Some time later, a letter from Berry arrived. He told me that, although he didn’t quite “get” the idea I’d been raving about, he’d taken encouragement from the letter. The response was short but, to my mind, epitomized Berry’s ethos: honest, gracious, and, especially, grounded.

Jeff King is a writer and humorist who lives in Canada with his family. His work has appeared in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Johnny America, and elsewhere.

In the time-honored American tradition of self-absorption, I’m going to use Wendell Berry’s ninetieth birthday to talk about me. When I was twenty-five, my soon-to-be-wife gave me a copy of Home Economics, and it retuned my head and my heart—it’s on the very short list of books that changed my life (and that list also contains Berry novels and Berry poetry).

Within a year I’d left my very urban job—writing the Talk of the Town for The New Yorker—and indeed I’d left the city, never to return; the rest of my life has been spent in dirt-road America. And it’s been spent trying to protect the planet that Berry helped me see, and the community he helped me yearn for. I can’t quite explain the power of his prose, except that certain things I’d perhaps unknowingly suspected about myself and the world fell into place as I read him.

I’m lucky that I was reading Ed Abbey at the same charged moment, because that helped me love the wild as fully as the pastoral, and the irreverent as fully as the good. The two of them were my introduction to the wider world of “nature writing” with its many heroes. This is a world Wendell has helped shape and nurture, just as he has shaped and nurtured the world of the farmers market. For a man who has mostly stuck at home, his influence on the nation, the planet, and the civilization has been deep, and will grow. He has set in motion forces (some small, such as myself; some much larger) that will for decades to come flavor our sense of what should be, what can be, and what must be.

Bill McKibben is the author of many books, including The End of Nature and Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future, and edited the LOA volume American Earth. He is scholar in residence at Middlebury College.

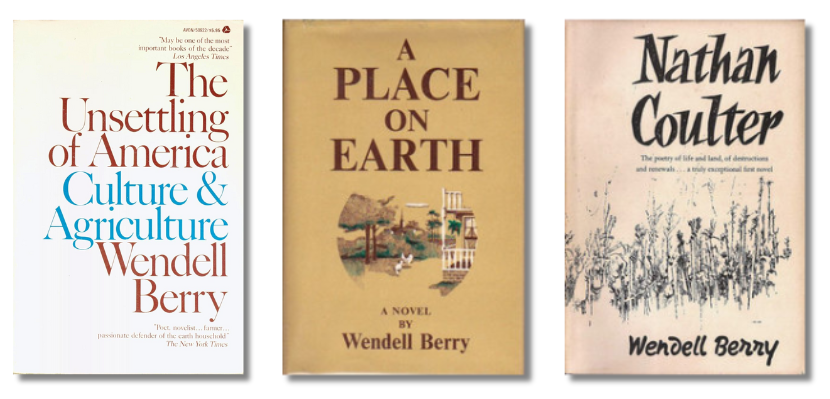

Jackets of three books by Berry: The Unsettling of America (Avon, 1977), A Place on Earth (Harcourt, Brace & World, 1967), and Nathan Coulter (Riverside Press, 1960)

Many people have had moments of humiliation, but I can testify that I had a smartphone alarm go off while sitting at the kitchen table with Wendell Berry. I was already nervous to be there on that Henry County farm with the man who, perhaps more than any living person, had shaped and reshaped my view of the world, with his poems and novels and essays, since I was a teenager. I suppose it could have been worse, but only if I had pulled up on a tractor. Since my ringtone was the sound of crickets chirping, I momentarily considered pleading my case that it was the sound of the peace of wild things, but I stopped, looking at the floor, blushing. “Well,” Mr. Berry said, with a shrug and a smile. “We’re all sinners.”

I’m a Baptist preacher and was, at the time, the dean of the Southern Baptist seminary down the highway from Port Royal in Louisville. Berry is a Baptist too, but, he would confess, not a very good one. He, like Jayber Crow, could describe himself as “maybe the ultimate Protestant, the man at the end of the Protestant road,” for as I have read the Gospels over the years, the belief has grown in me that Christ did not come to found an organized religion but came instead to found an unorganized one. I guess a Berryite with a smartphone could be called an “unorganized” one too.

As I left the house, I realized that Berry had just reinforced up close what he had taught me from afar. My problem, though, was not so much that I got caught with a machine as that too often I think I am one.

He showed us what it means to be not points of data but members of one another. And he did it by leading us to love a people in a town that exists only in Berry’s imagination, and now ours.

“The most radical influence of reductive science has been the virtually universal adoption of the idea that the world, its creatures, and all the parts of its creatures are machines—that is, that there is no difference between creature and artifice, birth and manufacture, thought and computation,” Berry wrote in his book Life Is a Miracle.

He wrote: “Our language, wherever it is used, is now almost invariably conditioned by the assumption that fleshly bodies are machines full of mechanisms, fully compatible with the mechanisms of medicine, industry, and commerce; and that minds are computers fully compatible with electronic technology.”

That way of thinking, Berry argued, leads us to exploit what we value, but not to defend it. For that, he argued, we needed to start with affection, and with a sense of reverence before the mystery that is not just “humanity” but each particular human life.

Berry did more than tell us this, though, he embodied that way of seeing in the lives of characters we came to love: Andy and Nathan and Hannah and Jayber, even Marcus who could have stayed out of trouble “if he’d had been tireder at night.”

To write those people took more than what Berry called “statistical knowledge,” but imagination which Berry defined for us in the words of Hannah Coulter as “knowledge and love.” He showed us what it means to be not points of data but members of one another. And he did it by leading us to love a people in a town that exists only in Berry’s imagination, and now ours.

“Better than any argument is to rise at dawn and pick dew-wet red berries in a cup,” Berry the poet told us. He let us pick those berries with him, at least in our minds. He was a Jeremiah, to be sure, standing alone in an era in which cultural and agricultural decisions might soon all be made by artificial intelligence. But Jeremiah always knew that after all the jeremiads were over, we could practice resurrection anyhow.

We’re all sinners; that’s true. But we’re not one of us a machine. We have more than we know, and we know more than we can say. Ninety years of Wendell Berry, standing by his words, taught me that.

Dr. Russell Moore is editor in chief of Christianity Today and the host of The Russell Moore Show.

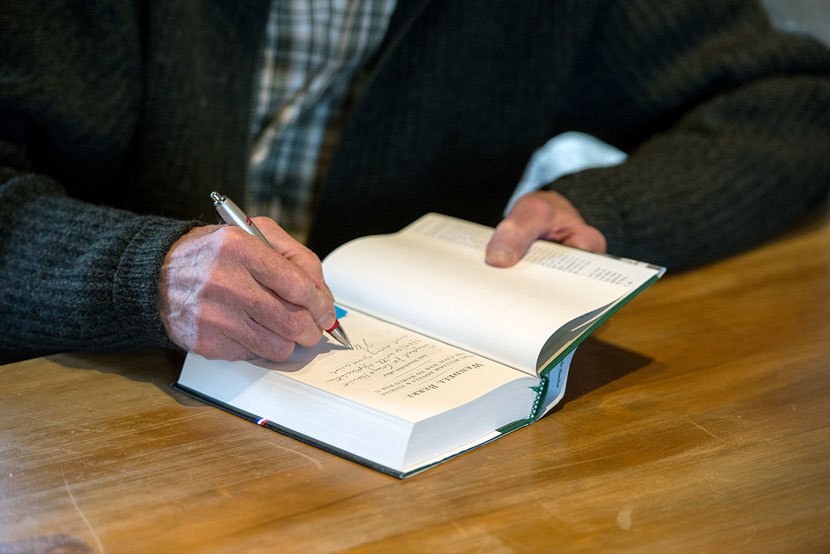

Berry signs a copy of Port William Novels & Stories (The Civil War to World War II) at the Berry Center (Virginia Berry Aguilar / The Berry Center)

“The Cheerful Farmer”

“Mr. Berry, my name’s Andrew. We met about three years ago at your house.” He smiled down at me (I’m always struck by how tall he is), showing no hint of recollection of the two hours we spent in his living room. “Was I nice?” he asked, eyes twinkling. “Yes sir, you were.” “Well, good!” he said with a clap on my back and a jolly grin as he turned away to the rest of the crowd. And that was that. I’ve had the pleasure of meeting Wendell Berry a few times, and at no point have I gotten the sense that he remembered me—nor has it bothered me one bit. His kindness is genuine and he meets a lot of people, so it strikes me as refreshingly honest that he doesn’t pretend.

If all you knew of Wendell Berry was his writing, you might miss the fact that he’s so cheerful. When I finished my first Berry novel, Jayber Crow, I wept. The aching beauty of the prose, the depictions of the ravaging of creation, the orphaned narrator’s loneliness, the doomed love story—they all give the book, for me, an aura of exquisite sadness, which in a Tolkienesque way is the jewel in the book’s crown. That same sadness is quietly present in all the Port William stories, which isn’t to say that the stories are all sad. There’s comedy aplenty in Burley Coulter’s antics and Ptolemy Proudfoot’s befuddled love for Miss Minnie, not to mention the colorful vernacular that abounds in nearly every conversation. But hovering over it all is a grief brought on by loss. The world of Port William is beautiful, but we know it’s passing away, and his characters seem to know it too.

When we turn to his poetry and essays, we’re met with other aspects of Wendell’s passions. With poetry it’s his deep waters: his love for his wife, his moral outrage as the Mad Farmer, his wonder at the beauty of the given world as well as his fear of its destruction. The essays, on the other hand, are mostly an exercise in conviction. Don’t read them unless you’re prepared to reckon with your responsibility to love your neighbor, and also creation, as yourself. It’s in the essays where we encounter most starkly Berry’s great intellect, speaking with authority about Milton or complex social issues or even science, right along with his knowledge of ploughing with a team of horses. It’s the essays, too, where his tone is least apologetic and most urgent, jarring us into action before it’s too late. But in neither the poetry nor the essays do we encounter much of his cheerfulness, if any.

Wendell’s writing is a house with three entrances: fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Whichever door you choose you’ll end up in the same place, hearing the same sermon.

I believe the lasting power of Wendell Berry’s work won’t be the novels, the poetry, or the essays in isolation, but in the combination of the three, braided together into a lovely knot that speaks of the preciousness of creation—a creation that includes stories and communities and land and also the people called to work it and keep it. I once heard it said that every preacher has just one sermon. Every Sunday is a variation on a theme. As a songwriter and novelist I feel the same: the older I get the more my own songs and stories reveal themselves to be cut from the same cloth, grown from the same garden. We can’t help but repeat ourselves. Wendell’s writing is a house with three entrances: fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Whichever door you choose you’ll end up in the same place, hearing the same sermon.

Still, I’m grateful that I’ve spent some time with Wendell (whether he remembers it or not) because it’s reminded me of the difference between a person and a persona. If you’re going to love the world enough to care for it, if you’re going to spend your life in community (the communities of marriage and family, as well as the broader communities of friendship and citizenship), pouring yourself into book after book, there needs to be more to you than lament, outrage, protest, and activism, however grounded those things are in love. Love, as the best shaper of our souls, ought to be conforming us to the image we imperfectly bear, and if all of Wendell Berry’s work had turned him into a contrarian grump, despairing of the world and retreating into the hell of himself, I don’t think I’d put much stock in that one sermon he’s been preaching for fifty years.

But as it is, the Wendell Berry I’ve encountered in person has been one with a glimmer in his eye, with a quick smile and a boisterous laugh, one who has borne the cost of true hospitality by opening his home every Sunday to perfect strangers whom he hopes to be nice to. That’s the kind of person I want to grow into. I’m inclined to take Wendell’s written words seriously because he doesn’t seem to take himself seriously. That’s the kind of neighbor I’d like to have. It’s the kind I’d like to be. The serious business of being human means being “joyful, though you’ve considered all of the facts.” Cheerful too, I’d argue.

At that first apparently forgettable meeting with Wendell and Tanya and a few of my friends, he told a story about a neighbor kid who bumped into a journalist at their fence line. The reporter said to the boy, “What do you think of the fact that Mr. Berry is a famous author?” The boy replied indignantly, “He is not! He’s my neighbor.” Wendell grinned and said he’d never been paid a finer compliment.

Andrew Peterson is a singer, songwriter, author, and founder of the Rabbit Room. He and his wife, Jamie, live in Nashville, where they do their best to tend a property called the Warren.

Watch: Wendell Berry at the Agriculture for a Small Planet Symposium, July 1, 1974

For many years, I’ve been an avid reader and admirer of Wendell Berry and his writing, and his holistic emphasis on stewardship of natural and human resources.

I’m a well-published poet, and when my ideas for new poems seem to falter and dry up, my frequent resource for renewal is to bury myself in Berry’s poems and essays and find refreshment there. I have a son who is not himself a poet, but a successful businessman who also finds beauty and meaning in nature poetry. Every week he and I read together from a poet such as Berry or Mary Oliver to give us a fresh start and a cause for creative fervor!

ORCHARD

The strong air of winter, my old friend

of many years, sighed against the house

all last night, a cold music—that icy wind,

blowing like regret through the neighbor’s

old apple orchard, a reminder of mortality.

With sharp memories of Fall, long ago,

when those over-burdened branches, obeisant,

bent low to the ground, like tired gymnasts,

as if awaiting our applause. Years,

now, since the trees bore any edible apples,

but this Fall, as always, the rosy fruit are falling,

each with a soft thunk—one, and one, and another,

with a slow leak of juices, a rich fermentation

sinking into the soil, turns the deer tipsy

as they root and nibble. Each apple so splendid

to look at, so full of worms at the heart.

Luci Shaw is the author of fourteen volumes of poetry and is a charter member of the Chrysostom Society of Writers.

Portrait of Berry (Guy Mendes) against a backdrop of the Berry Center and a 1784 map of Kentucky

The inspired work of Wendell Berry is a gift. It offers us a sense of the past, a hope for the present, and a path to our future. If we would only listen.

Jack Shoemaker was the cofounder and editor-in-chief of North Point Press, and later cofounded Counterpoint Press. He has worked with Wendell Berry for more than fifty years.

One of the luckiest accidents of my life is getting to know Wendell Berry, who is that most rare thing: an honest-to-God genius. He is so American, one of those original thinkers endowed with not only his deep sense of both literature and history but the prophetic vision and the gift of language to say those things the rest of us would be, simply, lost without.

Who aside from Wendell Berry writes what we recognize as being vital to our coherent existences? And writes too with the same brilliance as a poet that he does as an essayist, as a novelist, and so perfectly in that most difficult of narrative forms, the short story?

The world is a different place because Wendell Berry was born in Henry County, KY, ninety years ago. And we as a people are changed because this man has spent his entire working life telling us some of the hard truths of who we are as Americans. Wendell’s long-form storytelling feels inspired, by which I mean, God-given. The title story of Wendell’s masterful Watch With Me is that rare thing, a perfectly realized entertainment retelling verses from Matthew as the gospel according to Ptolemy Proudfoot.

How lucky we are to have had him and to have him still.

Jane Vandenburgh is the award–winning author of two novels, Failure to Zigzag and The Physics of Sunset, as well as Architecture of the Novel, A Writer’s Handbook and The Pocket History of Sex in the Twentieth Century, A Memoir. She has taught writing and literature at U.C. Davis, the George Washington University, and, most recently, at Saint Mary’s College in Moraga, CA.

“Eating is an agricultural act.”

Wendell Berry wrote this simple statement in his 1989 essay “The Pleasures of Eating.” It was the first thing of Wendell’s that I ever read, and was the moment when I first fell in love with his profound, provocative philosophy. In one elegant phrase, he articulated a fundamental truth that has defined how I think about food. We are not divorced from the land we live on, Wendell is saying; we are not merely passive consumers, as industrial food suppliers would so love for us to believe. Wendell is telling us that we have agency: to choose what to eat, to know where our food comes from, to find the deep pleasure that comes from growing and harvesting and preparing our own food. Every time we eat, we participate in something bigger than ourselves—and in that simple act of eating, we have the power to reconnect with nature, and each other.

Here we are, nearly forty years after Wendell first wrote those words, and we are just beginning to understand how true they are. Wendell has a philosopher’s way of distilling truths long before the rest of the world has arrived at them—and I have no doubt that ninety years from now the world will be marveling at the power, beauty, and prescience of Wendell Berry’s ideas.

Alice Waters opened the first farm-to-table restaurant in the United States, Chez Panisse, in 1971. A restaurateur, chef, and food activist, she was a leading proponent of the Slow Food movement.

Mary Berry with her father in Louisville, KY, in 2019 (J. Tyler Franklin)

One night in 1964, my father came home from his editorial office at Harcourt Brace and animatedly described his new writer: a lanky young man in an open-necked shirt and scuffed shoes who sat with his elbows on his knees, telling amusing stories in a slow Kentucky cadence. They worked together for thirteen years: two technophobes who loved classical literature and sometimes preferred the company of birds to that of humans. Wendell, as we all called him in our house, was astoundingly prolific: his poetry, essays, and novels eventually filled a bookshelf in our living room. My brothers and I particularly liked his pastoral poems and his scolding maxims. “Rats and roaches live by competition under the law of supply and demand; it is the privilege of human beings to live under the laws of justice and mercy.” Critics called him a crank. Admirers considered him a prophet. Berry’s most influential teacher, Wallace Stegner, once wrote to him, “Your books seem conservative. They are actually profoundly revolutionary.”

When my parents died, I inherited a number of Wendell Berry first editions and a heavy Jiffy Bag containing the Berry/Wickenden correspondence, 1964 to ’67. It was a delightful exchange of views on everything from the use of horse manure as compost to the Vietnam War. Like any self-respecting writer, Wendell sometimes bristled at editorial suggestions, but he was funny and acutely self-aware. In 1969, he wrote to my dad about the underwhelming response to The Long-Legged House: “I’m glad you told me the book hasn’t yet sold 2,000 copies. The particularity of that saves me a lot of trouble trying to imagine how poorly it must be doing.”

The letters inspired me to write to Wendell—by hand, of course. He has never owned a TV, sent an e-mail, or used a computer. A week or so later, I got a long, warm response, in pencil on sheets from a yellow legal pad. We began our own ongoing conversation by mail. I look forward to his gentle admonitions about my views on conservation and politics—and to his disclosures about what he is writing, as he approaches ninety, at his worktable in the long-legged house in the woods of rural Kentucky. He kindly signs his letters, “Your friend, Wendell.”

Dorothy Wickenden is a staff writer at The New Yorker and author of The Agitators: Three Friends Who Fought for Abolition and Women’s Rights and Nothing Daunted: The Unexpected Education of Two Society Girls in the West. Executive editor of The New Yorker for twenty-six years and host of its podcast The Political Scene from 2007 to 2022, she wrote a profile of Berry that appeared in the magazine in 2022.