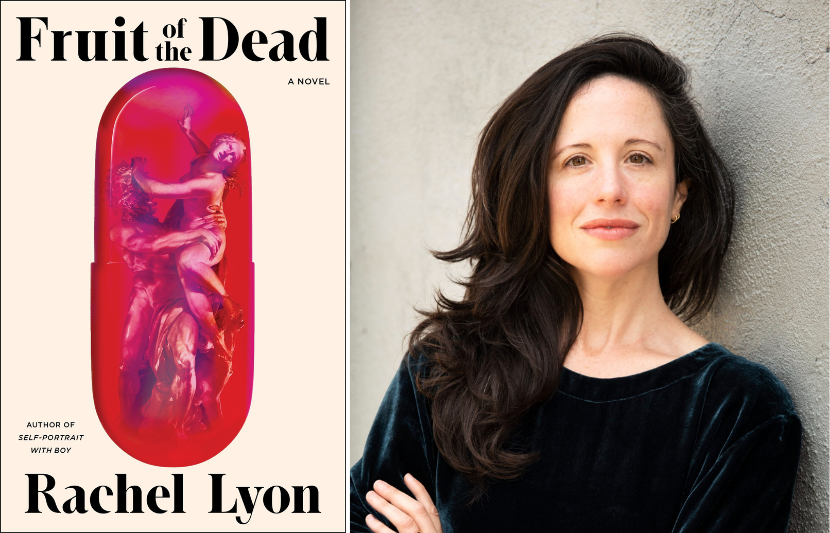

Fruit of the Dead by Rachel Lyon (Scribner, 2024; photo by Pieter M. van Hattem)

A myth is never fixed in time and place. Almost by definition, it evolves and adapts, breaks apart and reconfigures, retaining its familiar lineaments and explanatory power no matter when, where, and with whom it plays out. In Rachel Lyon’s sophomore novel, Fruit of the Dead, published this week by Scribner, the ancient story of Persephone’s abduction by Hades serves as the frame for an ultramodern tale of capture, consent, addiction, and complicated desire, set amid the roil of a twenty-first century capitalism gone off the rails.

When eighteen-year-old Cory is swept away to a charismatic but ethically compromised billionaire’s private island, she finds herself stuck in the fraught gulf between the independent adulthood she hopes to claim and an impulsive, aimless immaturity she can’t quite shake. As her feelings for her Luciferian host—a pharmaceutical magnate whose company’s painkiller business has landed him in legal hot water—toggle between attraction and revulsion, her mother abandons her high-powered career to track her wayward daughter down. But will Cory, newly queen of her captor’s hedonistic underworld, even want to be rescued?

“A novel as irresistible and devastating as its namesake; I devoured it in a single day,” writes author Melissa Febos. “Lyon has spun an utterly absorbing, lush, and terror-laced retelling of an ancient archetypal tale—a young woman tempted and taken, a mother’s feral grief—that is both timeless and crisply contemporary.”

Below, Lyon shares a number of works—including one coffee-stained, hand-photocopied tome—that shaped her writing and gave her hope in the midst of calamity.

Every book asks its own questions and suggests its own particular paths of inquiry. This past year, as I’ve worked (sporadically at best) on my third novel, I’ve been reading books told in reverse chronological order, from the end of a story to its beginning.

How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents by Julia Alvarez (Algonquin, 1991)

Of the American novels that have played with this form, perhaps the best known is Julia Alvarez’s beloved 1991 best seller, How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents, a buoyant and virtuosic story of emigration, assimilation, identity, and sisterhood, told in fifteen chapters that span thirty years.

First Light by Charles Baxter (Viking, 1987)

Then there is Charles Baxter’s exquisite 1987 novel, First Light, which happens also to be a story about siblinghood. It follows Hugh and Dorsey from middle age, which finds Hugh a car salesman who still lives in his hometown, and Dorsey a brilliant physicist (her research subject is, of course, time) with a blind son and an over-the-top actor husband. As the novel moves backward through Hugh and Dorsey’s thirties, twenties, and teens, the reader learns more about the siblings, particularly Dorsey’s complicated love life and fragile motherhood. By the time it ends, they are very young children, all of life awaiting them.

I embarked on this research for obvious reasons: I am trying to write a novel that unfolds in reverse chronological order. I’m interested both in the opportunities such a structure might present (a particularly writerly excavation of character, the element of baked-in mystery) and in its pitfalls (forced nostalgia). In my experience, however, it isn’t often that novel research is guided by such a clear and specific principle. Research for my second book was more intuitive, more elusive.

My son grew inside me, colonizing my body, altering my life and self in ways foreign, unknowable, and irrevocable; the virus spread around me, into other bodies, taking lives, altering everything.

Fruit of the Dead is a retelling of the Persephone myth, an addiction narrative, a coming-of-age story, a love story, a seduction. I began it the summer before my debut novel was published, a year when I was reading with hunger, maybe even desperation.

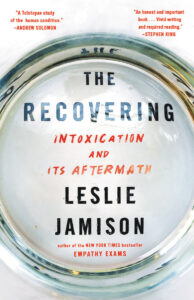

The Recovering by Leslie Jamison (Little, Brown, 2018)

For one thing, I didn’t know what to do with my evenings anymore. I’d quit drinking a month before the book came out. For another, I could think again, more clearly than I had in years. As it happened, my debut shared a publication year with two books that would closely inform my second novel. The first was Leslie Jamison’s humbly expansive, profoundly intelligent, deeply moving memoir The Recovering. That book helped me analyze—and, eventually, fictionalize—a process that had been going on in me, largely unexamined, for fifteen years or longer.

Trust Exercise by Susan Choi (Holt, 2019)

I knew I was writing a book about a very young woman and a middle-aged man, so I read several books concerning such relationships, notably Susan Choi’s absorbing and disturbing Trust Exercise, which came out in 2019.

It was still 2018 and the project was still quite fresh, however, when I read Lisa Halliday’s slim and poignant novel Asymmetry. The tenderness with which Halliday handled her characters moved me. When I began to understand that I was retelling the story of Persephone, Halliday’s radical structure freed me.

Asymmetry by Lisa Halliday (Simon & Schuster, 2018)

My problem was this: I had been writing my protagonist’s mother in a tense, tightly wound first-person voice, totally different from the lush and rambling third person I used for her teenaged girl. Asymmetry suggested a solution: write one book as if it were two.

For years thereafter I retained a structure for Fruit of the Dead very similar to Halliday’s: a three-part book whose final section was more like a “slim, revelatory coda,” to quote Katy Waldman’s review of Asymmetry for The New Yorker. Eventually, when Fruit was accepted for publication, my wise editor recommended that we shuffle together the first two sections, like a deck of cards. I tried it; the book was better, so we kept it that way. The mark Asymmetry left on my book is invisible today.

Averno by Louise Glück (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006)

There were other breakthroughs. In my latest stage of work on Fruit I returned often to Louise Glück’s Averno, as one might turn to the tarot. During so-called “lockdown” in early 2020, when I was in the second trimester of my first pregnancy, I read The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson’s rigorous, elliptical memoir. My son grew inside me, colonizing my body, altering my life and self in ways foreign, unknowable, and irrevocable; the virus spread around me, into other bodies, taking lives, altering everything.

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson (Graywolf, 2015)

In the midst of all this, Nelson’s radical optimism gave me hope. In her pregnancy I found a mirror for my own. In her preoccupations—with the Argo and radical processes of remaking, with claiming the body as a site for discourse—I found dialogue even in my isolation. Some of that stuff ended up—in that upside-down and sideways way in which the real becomes the fictional—in the voice of my protagonist’s mother.

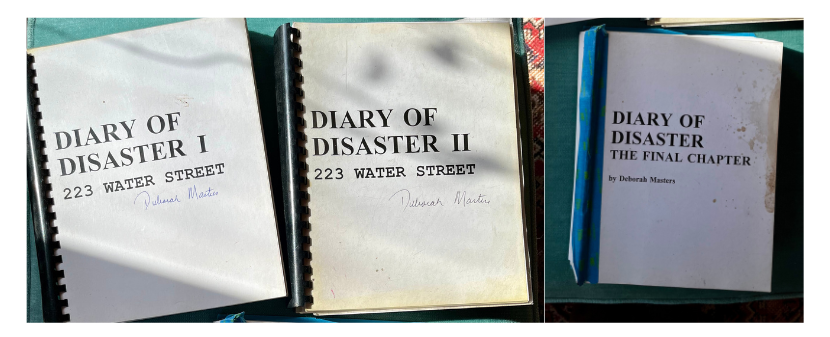

I began work on my first book, Self-Portrait with Boy, ten years ago, so my memory of that time is vague. The main text I recall reading for research was a three-volume, hand-photocopied tome entitled “Diary of a Disaster,” compiled by the sculptor Deborah Masters and given to me by the painter Lance Rutledge. Masters and Rutlege were two of the dozen or so artists who lived and worked in the same Brooklyn warehouse that my family did during the formative years of my early childhood.

“Diary of Disaster,” compiled by Deborah Masters (photo courtesy of Rachel Lyon)

This building closely informed the setting for my book, and the struggles of its tenants to keep their homes and studios—against intense pressure from their landlord, who eventually sold to a developer that transformed the place into criminally small luxury apartments—informed its subplot. At any rate, “Diary of a Disaster” was a novelist’s dream come true. It contained more sordid real estate drama than I ever could have invented, in the form of receipts, legal papers, snapshots, and notes written by hand.

I studied other media for that book, too—photographs especially, for example the work of Diane Arbus and Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency—but I don’t remember experiencing the great pleasure of being influenced by a preexisting book, intentionally or otherwise.

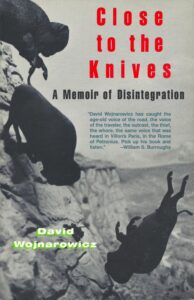

Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration by David Wojnarowicz (Vintage, 1991)

If I could give myself-as-I-was any book at all, in the interest of influence, it would be Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, David Wojnarowicz’s raw, iconoclastic 1991 memoir-in-fragments, which evokes the desperation, fearless rage, and fierce commitment to art in AIDS-plagued early ’90s New York City better than anything else I have read.

I would give myself that book, but I don’t know that I-as-I-was would have read it. I was so anxious in those days. I had trouble focusing well enough to read at all. I was still very young, I think now, and Self-Portrait was my first novel. I was still hung up on some abstract principle of sui generis originality.

Rachel Lyon is the author of Self-Portrait with Boy, which was a finalist for the Center for Fiction’s 2018 First Novel Prize, and Fruit of the Dead, which has received starred prepublication reviews from Kirkus, Publishers Weekly, and Booklist, and been named a most anticipated book of 2024 by Elle, LitHub, and other publications. Rachel’s short work has appeared in One Story, The Rumpus, Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, and elsewhere. She has taught creative writing at various institutions, most recently Bennington College, and lives with her husband and two young children in Western Massachusetts.