Callum Turner as John “Bucky” Egan in Masters of the Air (Apple TV+)

For those of us who’ve found ourselves riveted to Masters of the Air, Apple TV+’s saga of the Eighth Air Forces’ “Bloody Hundredth” Bomb Group during World War II, it can be hard to remember—amid the pyrotechnic aerial battles, frisson-inducing score, and major wattage of stars Austin Butler and Callum Turner—that these harrowing missions actually happened in the skies over war-torn Europe eighty years ago. But nothing immerses us in the nerve-racking reality of these operations more than the firsthand accounts written by men who flew in the B-17s—a number of which have appeared in Library of America volumes.

With the season finale coming up on March 15, let’s rewind to episode three, depicting the monumental Schweinfurt–Regensburg mission in August 1943. A massive endeavor involving 376 bombers from 16 groups, Mission No. 84 (as it was known within the Eighth Air Force) was at once a highly ambitious plan to devastate German war production and a bloodbath that saw 60 B-17s shot down and more than 500 airmen killed or captured.

B-17s of the 100th Bomb Group (National Archives at College Park)

The American plan that day was two-pronged: one wing of bombers, commanded by Brigadier General Robert B. Williams, targeted the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt while another, led by Colonel Curtis E. LeMay, aimed for the Messerschmitt fighter plant in Regensburg. Dividing the force, the thinking went, would confuse German air defense commanders, somewhat compensating for the fact that large portions of the B-17s’ flight path over enemy territory would be beyond the range of Allied fighter escorts.

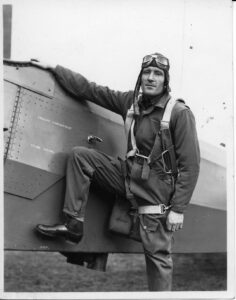

Beirne Lay, Jr. (Public Domain)

Adding to the complexity—and the danger—the Regensburg force wouldn’t return to their bases in England following the attack, but rather turn south, cross the Alps, and land at airstrips in the Algerian desert.

Beirne Lay, Jr., who flew with the 100th on the Regensburg mission, described the surreal and nightmarish world crews encountered on this fateful flight. In “I Saw Regensburg Destroyed,” his arresting article about the raid included in LOA’s Reporting World War II: American Journalism 1938–1944 volume, he recalls:

A shining silver rectangle of metal sailed past over our right wing. I recognized it as a main-exit door. Seconds later, a black lump came hurtling through the formation, barely missing several propellers. It was a man, clasping his knees to his head, revolving like a diver in a triple somersault, shooting by us so close that I saw a piece of paper blow out of his leather jacket. He was evidently making a delayed jump, for I didn’t see his parachute open.

A B-17 turned gradually out of the formation to the right, maintaining altitude. In a split second it completely vanished in a brilliant explosion, from which the only remains were four balls of fire, the fuel tanks, which were quickly consumed as they fell earthward.

I watched two fighters explode not far beneath, disappear in sheets of orange flame; B-17s dropping out in every stage of distress, from engines on fire to controls shot away; friendly and enemy parachutes floating down, and, on the green carpet far below us, funeral pyres of smoke from fallen fighters, marking our trail. Had it not been for the squeezing of my stomach, which was trying to purge, I might easily have been watching an animated cartoon in a movie theater.

Lay would not be the only airman to liken the experience to a fiction film. In The Fall of Fortresses, included in LOA’s forthcoming World War II Memoirs: The European Theater (November 2024), B-17 navigator Elmer Bendiner fills in the Schweinfurt side of the story:

I do not recall seeing a rocket actually hit a B-17. I remember only the fireworks and the gust of wind. The smell and sight of battle are still with me—the acrid gunpowder and the disordered plexiglass cabin—but I cannot recall a sound of battle except the clump and clatter of our own guns. The throb of our engines was so monotonous as to leave an effect of profound quiet as if we were in a soundproof chamber beyond which the enemy whirled as in a silent cinema.

B-17s encountering heavy flak over Germany (Public Domain)

There is a haunting irony that these scenes—uncanny and borderline incomprehensible even to the men who witnessed them—would form the basis for the eyeball-cramming, CGI-enhanced battle sequences of Masters of the Air. For all the vertiginous camerawork and cacophonous combat of the show, Lay’s and Bendiner’s recollections speak to the unspectacular but no less dramatic aspects of being in a Flying Fortress as it weathered a storm of flak bursts and cannon shells: the unbearable tension, the eerie quiet inside the cockpit, the emotional detachment required to stay sane in such hellish conditions.

But even with the Regensburg force suffering heavy losses, the mission pressed on. Lay paints a picture of the remarkable bravery of Gale “Buck” Cleven—the pilot portrayed by Butler in Masters of the Air but left unnamed in his article due to wartime security concerns—in the lead-up to bombs away:

At this hopeless point, a young squadron commander down in the low squadron was living through his finest hour. . . . Now, nearing the target, battle damage was catching up with him fast. A 20-mm. cannon shell penetrated the right side of his airplane and exploded beneath him, damaging the electrical system and cutting the top-turret gunner in the leg. A second 20-mm. entered the radio compartment, killing the radio operator, who bled to death with his legs severed above the knees. A third 20-mm. shell entered the left side of the nose, tearing out a section about two feet square, tore away the right-hand nose-gun installations and injured the bombardier in the head and shoulder. A fourth 20-mm. shell penetrated the right wing into the fuselage and shattered the hydraulic system, releasing fluid all over the cockpit. A fifth 20-mm. shell punctured the cabin roof and severed the rudder cables to one side of the rudder. A sixth 20-mm. shell exploded in the No. 3 engine, destroying all controls to the engine. The engine caught fire and lost its power, but eventually I saw the fire go out.

. . . . His crew, some of them comparatively inexperienced youngsters, were preparing to bail out. The copilot pleaded repeatedly with him to bail out. His reply at this critical juncture was blunt. His words were heard over the interphone and had a magical effect on the crew. They stuck to their guns.

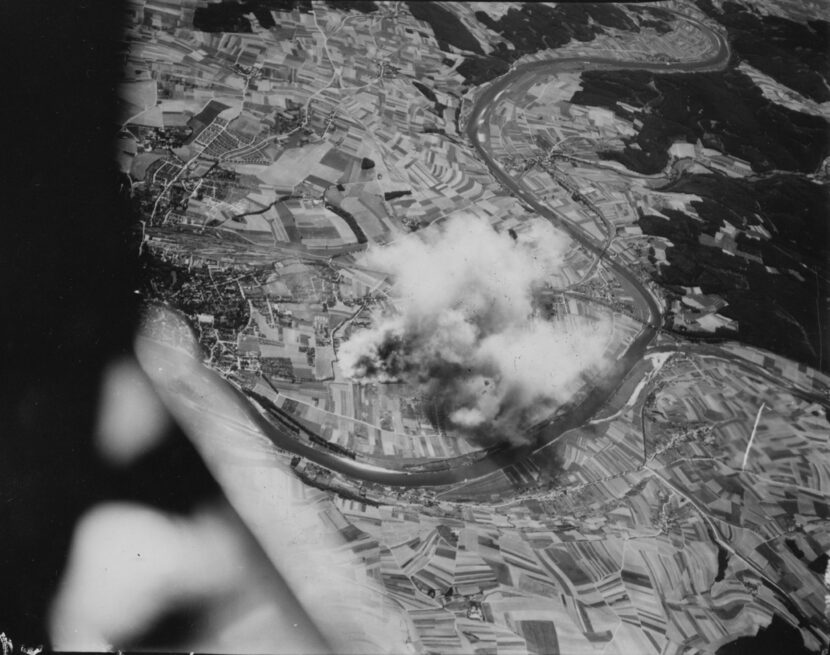

At long last, Lay’s wing reached Regensburg and dropped its bombs. “I looked back and saw a beautiful sight,” he writes, “—a rectangular pillar of smoke rising from the Me-109 plant. . . . Even from this great height I could see that we had smeared the objective. The price? Cheap. 200 airmen.”

Regensburg after being bombed by B-17s on August 17, 1943 (Public Domain)

The “Bloody Hundredth” ultimately lost nine of the twenty-one B-17s it sent on the mission, the most of any group in the operation. Battle-damaged and trailing smoke, with some crews bailing out into the Mediterranean en route, the surviving planes set down in Algeria. Lay writes:

With red lights showing on all our fuel tanks, we landed at our designated base in the desert, after eleven hours in the air. I slept on the ground near the wing and, waking occasionally, stared up at the stars. My radio headset was back in the ship. And yet I could hear the deep chords of great music.

B-17s flying over the Alps en route to North Africa after bombing Regensburg (Public Domain)

Was this music akin to the swelling score that plays during Masters of the Air’s opening credits? Stirring as it is, we’d do well to consider another potential soundtrack to this moment of exhausted relief: the still silence that is perhaps the only adequate response to the unspeakable. Bendiner writes of his own safe return to base following the Schweinfurt mission:

We had been in the air for eight hours and forty minutes. We had been in incessant combat for close to six hours. It had been fourteen hours since we had risen in the predawn. In that time sixty B-17s had been shot down, six hundred men were missing. The first major strategic air battle of the war had been fought. Did we win? Did we lose? Did we really see those planes burning on the ground? Did we see this one fall and that one fart black smoke from his engine? Whose chute opened? Whose did not? Questions turned in the hollow mind bereft of thought, like an awl in wormwood, biting into nothingness, the nothingness of spent men at last asleep.

In the final analysis, the results of Mission No. 84 were mixed. The Messerschmidt plant at Regensburg was mostly destroyed; damage at Schweinfurt was more modest but nonetheless extensive. Still, the strike failed to significantly curtail German aircraft production, and when a follow-up raid on Schweinfurt in October 1943 resulted in the loss of another sixty B-17s, the entire strategy of conducting bomber attacks deep in enemy territory came under scrutiny. It would be several months before B-17s were dispatched on a comparable mission inside the Third Reich.

A heavily flak-damaged B-17 (U.S. Air Force)

This zoomed-out view, tallying the extent of the destruction, the number of casualties, the postmortem decisions of the strategists, is one way to take the measure of the Schweinfurt–Regensburg mission. But another is to put ourselves in the position of the men who flew that day—the bracing and terrifying perspective afforded by Lay and Bendiner’s narratives and brought vividly to life in Masters of the Air. As Bendiner explains, the dizzying complexity of battle at the command level is often obscure to those whose lives are on the line. “Such facts,” he notes, “are computed after the event and do not affect the morale of those who are mercifully limited to their own tiny circle of war.”

Watch the official trailer for Masters of the Air

The season finale of Masters of the Air will debut on Apple TV+ on March 15.

Discover more firsthand accounts from the Eighth Air Force in LOA:

• “Young Man Behind Plexiglass (An American Bombardier: August 1944)” by Brendan Gill in Reporting World War II: American Journalism 1944–1946

• “First Mission” by Bert Stiles in Into the Blue: American Writing on Aviation and Spaceflight (eBook)

• Excerpt from I’ve Had It by Beirne Lay, Jr., in Into the Blue: American Writing on Aviation and Spaceflight (eBook)