Snapshots of the Fitzgerald’s house in Redding, CT, and photograph of Flannery O’Connor in Milledgeville, GA (Britannica)

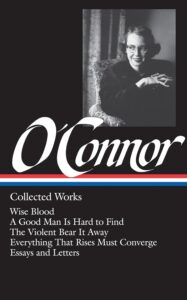

To mark the centennial of Flannery O’Connor’s birth this week, we present this essay from Library of America Editorial Director John Kulka on a trip he took in 2004 with O’Connor scholar William A. Sessions to the Redding, Connecticut, house of the author’s friends Robert and Sally Fitzgerald. In 2013 Sessions published Flannery O’Connor’s A Prayer Journal. He died in 2016.

“That year and a half Flannery lived with Robert and Sally Fitzgerald in Connecticut, from September 1949 to that terrible week before Christmas 1950, when O’Connor first began to show signs of the illness that would eventually kill her, marked the beginning of an important lifelong friendship,” Bill Sessions, the Flannery O’Connor scholar and editor, seated beside me in the passenger seat, explained on a warm summer afternoon in 2004. Thirty minutes earlier I had picked up Sessions and his wife, Jenny, at the New Haven train station. We were on our way to the former Fitzgerald residence in Redding, Connecticut, having received an invitation from the present owners to tour the house.

The former house of Robert and Sally Fitzgerald, with current residents, Bill Sessions, and John Kulka seated outside (courtesy of John Kulka)

It was there, in a drafty room above the Fitzgeralds’ attached garage, that O’Connor wrote the final chapters of, and made significant revisions to, her comic first novel, Wise Blood (1952), about a self-proclaimed backwoods evangelist who preaches the Church of Christ Without Christ “where the blind don’t see and the lame don’t walk and what’s dead stays that way.” In the author’s note to the second edition of Wise Blood, she characterizes the main character, the blasphemous Hazel Motes, as “a Christian malgré lui [a Christian in spite of himself],” unable to rid himself of “the ragged figure” moving “from tree to tree in the back of his mind.”

Sessions was at work on a biography of O’Connor and the section of the manuscript he was then drafting concerned the time his subject had spent in Connecticut when she was revising Wise Blood. He felt he needed to see the house in order to write about it.

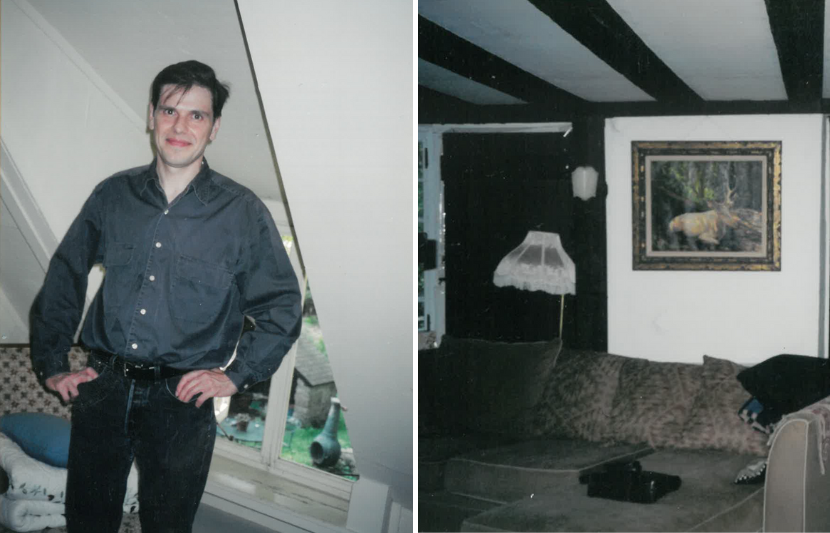

Sessions called our attention to the many small holes in the walls and ceiling, made by O’Connor during her stay. ‘Between beaverboard and timbering the field mice pattered as the nights turned frosty,’ Robert Fitzgerald recorded, ‘and our boarder’s device against them was to push in pins on which they might hurt their feet, as she said.’

He spoke of “Flannery” because Sessions was a close friend of O’Connor. He met her in May 1956, at Andalusia, the O’Connor farm in Milledgeville, Georgia, after one of his book reviews appeared in the Bulletin, the weekly newspaper of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Atlanta. O’Connor admired the review and extended an invitation to Sessions to visit. They remained friends and correspondents (typically “Billy” or “Mr. Billy” in O’Connor’s letters) until her death in 1964 at the age of thirty-nine. Doing the math in my head, I calculated that Sessions—born in 1928—must have been about twenty-seven or so when he met O’Connor, only a few years older than O’Connor was when she was a paying guest at the Fitzgeralds’ house.

O’Connor feeding birds in Milledgeville, GA (PBS)

Sessions and I had met a few times before for lunch or coffee, always in New York City, to discuss his work-in-progress, “‘Stalking Joy’: Flannery O’Connor, Her Life and Her Times.” I was then an editor for Yale University Press and hoped to publish the book when it was completed. Jenny, whom I’d not met before, sat in the back seat, wearing a pair of large sunglasses, her short gray hair combed straight back. Much quieter than her husband, she gazed out the window at the countryside.

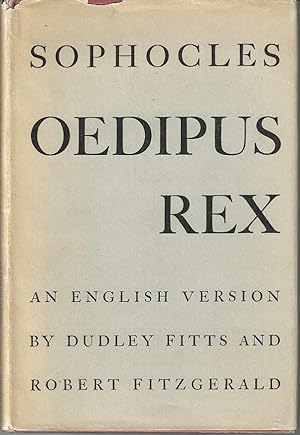

“Robert and Sally were each important to Flannery in different ways,” Sessions continued, in a lilting southern accent that made me picture diacritical marks above stressed and unstressed syllables. “Robert, then teaching at Sarah Lawrence, introduced her to new writers, new books, and new ideas—his and Dudley Fitts’s translation of Oedipus Rex, which had just been published, showed Flannery how Wise Blood needed to end after she had reached an impasse with Hazel Motes. Of course he had to blind himself with quicklime. It made perfect sense. Flannery had never read Sophocles before. In return, she foisted on him West’s Miss Lonelyhearts and Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying.” Sessions chuckled.

“I’d call that a fair exchange,” I said.

“Now Sally was a different matter,” he said, ignoring the comment. “Sally wasn’t an intellectual or even then a literary person, like Robert was. She was a kind of older sister to Flannery, a confidant, and her most important friend except for Betty Hester [the anonymous “A.” in O’Connor’s correspondence], to whom Flannery wrote some of her most remarkable letters. And later, of course, after Flannery’s death, Sally did so much to champion Flannery’s work.”

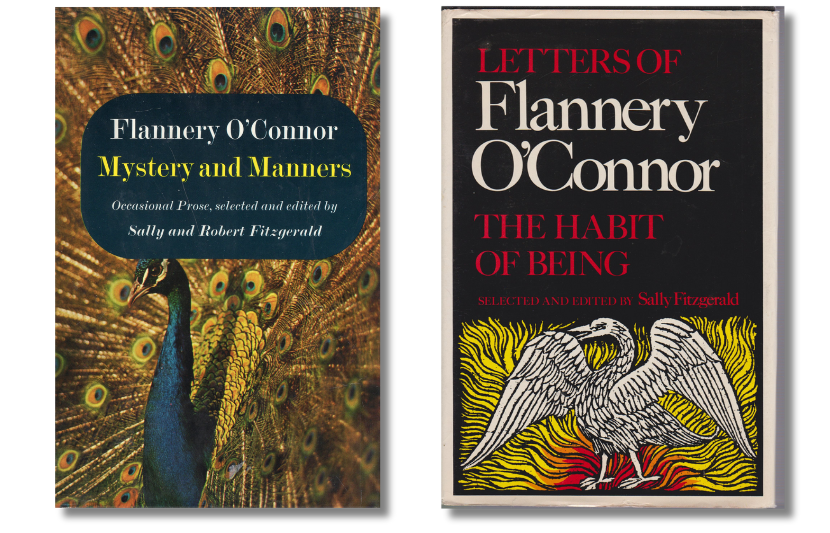

Sessions referred to the posthumous books of O’Connor’s writings that Sally Fitzgerald had been instrumental in publishing. With Robert, she co-edited Mystery and Manners (1969), a selection of O’Connor’s occasional prose, and then, by herself, she brought out The Habit of Being (1979), a selection of O’Connor’s letters, which was given an unprecedented special award by the National Book Critics Circle in 1980. She also edited for Library of America Flannery O’Connor: Collected Works (1988).

First-edition covers of Mystery and Manners, edited by Sally and Robert Fitzgerald, and The Habit of Being, edited by Sally Fitzgerald

“It’s unfortunate that Sally couldn’t finish her book,” Sessions said, shaking his head. He meant the biography of O’Connor she had been working on for decades, leaving behind at the time of her death in 2000 a congeries of notes and ideas that had never coalesced into a whole. Her failure to finish the book troubled Sessions, I knew, because he worried that, having taken the reins from Fitzgerald as the official biographer, he in turn might not complete the task.

Sessions’s fears proved at least partly justified. He would eventually complete a manuscript draft but did not live to see it into publication. An invaluable resource for future biographers, it remains, to my knowledge, without a publisher.

After getting us lost for a few minutes, I found Seventy Acre Road, the steep rural road the former Fitzgerald house was located on. Fifty years earlier, when the road was unpaved, it would have been a much rougher ride up the incline. Here and there lichen-covered stone walls were visible in the sun-dappled second-growth timber and laurel on either side of the narrow two-lane road. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries those stones were impediments to the farmers who had worked the land.

“Flannery would have walked down and back up this road, to and from the mailbox,” Sessions said. “It used to sit at the bottom of the hill.”

“We passed number sixty,” Jenny said from the back seat.

After backing up and turning around, I angled the car into the driveway of number sixty.

The stone-and-timber cottage that came into view in the clearing at the end of the driveway wasn’t what I expected. It looked like something from a Merchant Ivory film. “The local stone of the house, heavy and variegated, would have impressed a Georgian from the fall line [characterized by red clay and sandy soil],” Sessions later wrote in his manuscript. “The steep roof emphasized the effect of a squeezed down Tudor-cottage built to hold heat, with small windows that had white decorative shutters on either side of them. . . . The walkway from the parking space by the garage to this main door went by a large extending lawn marked by two massive ancient oaks.”

Robert Fitzgerald and Dudley Fitts’s translation of Oedipus Rex (Harcourt, Brace & World, 1949), a major influence on O’Connor’s revisions to Wise Blood

Seated in lawn chairs on a grassy area in front of the house, our hosts, Janet August and Amy Atamian, got up and greeted us warmly. They had prepared refreshments and hors d’oeuvres that were already invitingly laid out on a patio table, but we were eager to see the inside of the house. The main entranceway led into the living room, which had a massive fireplace, a rough stone floor, and a low ceiling that together suggested a cloister or monastery, to speak of the poetics of the house. It was easy to imagine the multiple ways the interior space would have delighted the devout young Catholic writer.

“Me and Enoch [Hazel Motes’s disciple] are living in the woods in Connecticut with the Robert Fitzgeralds,” O’Connor wrote to Robie Macauley several months after arriving in Redding. “Enoch didn’t care so much for New York. He said there wasn’t no privetcy there. Every time he went to sit in the bushes there was already somebody sitting there ahead of him.”

Before coming to live with the Fitzgeralds, O’Connor had been renting a furnished room in an apartment at 255 West 108th Street, between Broadway and Amsterdam. (Prior to that there were other, briefer stops in Manhattan, including the couch in Elizabeth Hardwick’s one-bedroom apartment.) “Flannery desperately wanted to live in New York,” Sessions said. “But she also needed to finish Wise Blood. Maybe living here was a kind of compromise, giving her enough solitude to write while keeping her within the ambit of literary New York and her publishers.

“It was Robert Lowell who introduced Flannery to Robert and Sally, and his influence on her decision to move in with them can’t be discounted. But Regina [O’Connor’s mother] was none too happy with Flannery’s decision to live in New York. That was a source of real friction between them.”

O’Connor with Arthur Koestler (left) and Robie Macauley in Iowa, 1947 (CC BY-SA 4.0)

As Sessions talked about O’Connor in the years after Iowa—Yaddo, Manhattan, and then Connecticut—the picture that emerged was one I couldn’t quite square with photographs of her hobbling about on crutches, dependent on the care of her mother, surrounded by peafowl pecking at the dust in front of the screened-in porch at Andalusia: O’Connor before any signs of her illness had manifested themselves, vibrant and full of energy, determined, like so many young American writers before and after her, to make a go of it in the literary Northeast.

O’Connor’s room and small bathroom were reached by means of narrow stairs accessed through the Fitzgeralds’ kitchen. Our hosts cautioned us to be careful going up the stairs and encouraged us to take our time. They would remain downstairs. Janet and Amy, who had purchased the house in 2001, had plans to remodel the garret but hadn’t yet gotten around to doing so, leaving it for the time being looking much as it had when O’Connor inhabited it.

The garret was brighter than the downstairs rooms, with three casement windows overlooking the grounds, the walls and ceiling covered by beaverboard. In his journal during this period, Robert Fitzgerald recorded that he and Sally had prepared the “austere” space for their boarder by purchasing a Sears, Roebuck dresser and putting a fresh coat of paint on the beaverboard. Sessions called our attention to the many small holes in the walls and ceiling, made by O’Connor during her stay. “Between beaverboard and timbering the field mice pattered as the nights turned frosty,” Robert Fitzgerald recorded, “and our boarder’s device against them was to push in pins on which they might hurt their feet, as she said.”

Kulka standing in the garret where O’Connor worked, and a snapshot of the house’s interior (courtesy of John Kulka)

Joining our hosts back in the yard, we relaxed in chairs gathered in a circle as Sessions described for us the daily routine O’Connor established for herself in the Fitzgerald house. After attending mass each morning with one of the Fitzgeralds (the other had to remain behind with their young children), O’Connor ate breakfast with the family in the dining room. Then she would “disappear” back upstairs to work on Wise Blood, writing for four hours before stopping for the day. She found she could not be productive for longer than that. Afternoons were for letter writing and helping Sally Fitzgerald with the children, by watching Hugh or Benedict, especially later, after Sally had given birth to the Fitzgeralds’ third child, Maria, while Robert was away at Sarah Lawrence. Little Benedict Fitzgerald would come to play his own part in O’Connor’s posthumous career, writing the screenplay for John Huston’s 1979 adaptation of Wise Blood. (More impressive to our hosts was his co-writing credit with Mel Gibson for the screenplay for the 2004 film The Passion of the Christ, then in theaters).

“Here, perhaps in this very spot, the Fitzgeralds and Flannery would gather outside in the warm summer months with a pitcher of martinis after the children had been put to bed,” Sessions said, looking about. “Yes, the year and a half she spent here was the happiest time of her life.”

In December 1950 after O’Connor had complained, only half-jokingly, of heaviness in her “typing-arms” and then genuine pain, the Fitzgeralds took O’Connor to a local doctor who diagnosed her with rheumatoid arthritis. In a note in The Habit of Being, Sally Fitzgerald recalls putting O’Connor on a train bound for Georgia, where O’Connor was returning for Christmas with her mother: “she was smiling perhaps a little wanly but wearing her beret at a jaunty angle. She looked much as usual, except that I remember a kind of stiffness in her gait as she left me on the platform to get aboard. By the time she arrived she looked, her uncle later said, ‘like a shriveled old woman.’ . . . A few nights later her mother called to tell us that Flannery was dying of lupus.”

Andalusia Farm, where O’Connor lived from 1952 until her death in 1964 (CC BY-SA 3.0)

During the drive back to the train station with Sessions and his wife, the mood in the car had changed subtly with the light in the sky, and the conversation turned to more mundane things—dinner plans and summer vacations. After our goodbyes at the train station, Sessions turned to me and added: “Well, you know, when Flannery was forced to live with Regina, she was really just getting started as a writer.”

Back in Georgia, O’Connor would complete the final revisions to Wise Blood. All four of her extraordinary books, including Everything That Rises Must Converge, her second, posthumously published collection, were completed during those fourteen years of declining health in Milledgeville, under the care of her mother. (Revisions to “Judgment Day,” the final story in Everything That Rises Must Converge, were made in July 1964, shortly before her death on August 3.) But to the enduring popular image of the sickly artist on her mother’s farm, surrounded by peafowl, I was glad to add another, contrasting snapshot: of the young O’Connor at the outset of her literary legacy, under the roof of friends, independent and in her prime, in the woods of New England.