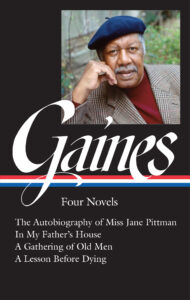

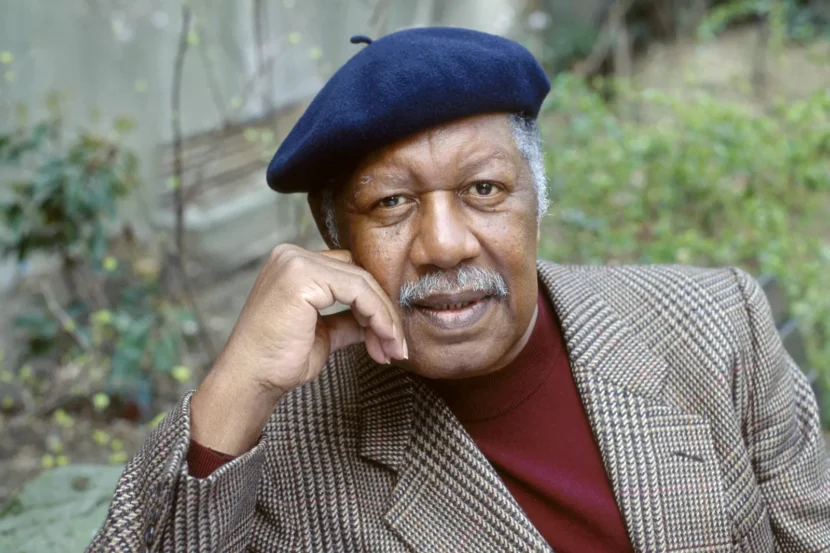

Ernest J. Gaines at the Riverlake Plantation in Louisiana (Adine Sagalyn)

Library of America is proud to present excerpts from John Wharton Lowe’s as-yet unpublished biography of Ernest J. Gaines, The Man Who Came Home: The Life and Fiction of Ernest Gaines. It includes commentary from Veronica Makowsky, Professor of English Emeritus at the University of Connecticut, who is preparing the biography for publication following Lowe’s death in August 2023.

When Ernest Gaines passed away on November 5, 2019, the world took notice of its loss. Appreciative and lengthy obituaries appeared in The New York Times and other major newspapers across the world. Although his novels and stories almost always concern the rural culture of south Louisiana that nourished and inspired him, readers and critics have understood that his “little postage stamp” of soil (Faulkner’s phrase for his own imagined county), with its array of cultures, represented all the major drawbacks and possibilities of the human condition.

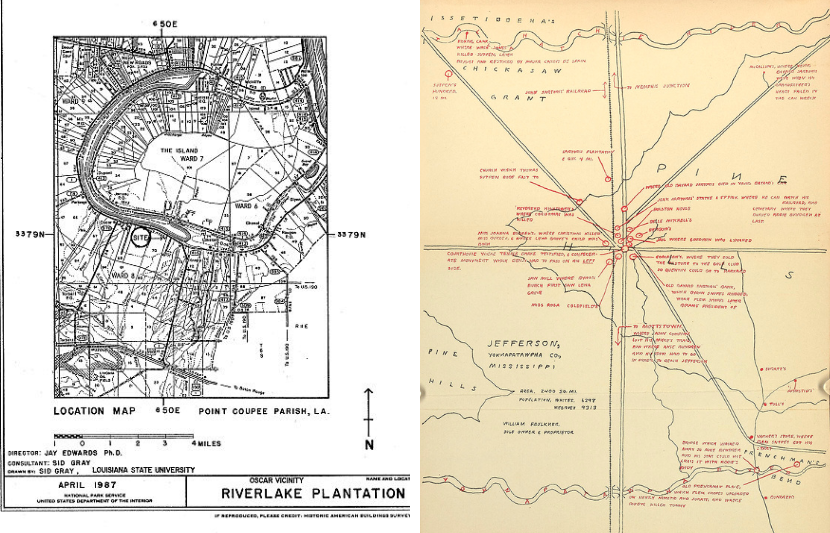

Map of Riverlake Plantation, Oscar, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana (Library of Congress) and map of William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County (Digital Yoknapatawpha, University of Virginia)

Further, while Gaines interrogated love, hate, class, and gender, the conundrum he presented of racial identity and the struggle to “stand” in a society determined to keep some people down provides access to both the South’s and the nation’s often tragic but also uplifting, and still unfolding, racial history.

He based his sweeping panorama in an alternate history, one that was for too long ignored. From his portrait of antebellum life in his neo-slave narrative The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971) to the fictions set in his own contemporary time, Gaines’s oeuvre provides apertures into the often unseen but immensely consequential operations of quotidian modes of racial, gendered, and class performances, and of the social pressures that dictate both oppressive and servile posturing.

The appeal his works have had has been global; they have been translated into eighteen languages, including French, Spanish, German, Russian, and Chinese.

On Gaines’s Childhood Milieu

Riverlake Plantation, the nearby town of Oscar, and False River formed the landscape of Ernest Gaines’s childhood and became the world of his fiction.

False River was essential for the people who lived on its shores. In the early days of settlement, before the Mississippi changed course completely, crops were loaded onto vessels for transport to New Orleans. The river provided fish as well as a site for baptisms. Many social events took place on the batture (a Louisiana term for riverbank). False River, in Ernest’s works, becomes a kind of mystical body of water, one associated with memory and meditation. As Melville’s Ishmael proclaimed, “meditation and water are wedded forever.”

Oscar, the nearest town, was quite isolated when Gaines was a child. It was fourteen miles to the nearest city, New Roads, and thirty miles to Baton Rouge, the state capitol, at a time when few residents of the Quarters had access to automobiles. The Oscar post office wasn’t established until 1895, when it offered a new window to the world, even for those who couldn’t read; residents eagerly awaited the arrival of the “wonder books,” the Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward catalogues, each year, and Gaines would help his elders fill out and mail orders.

My church is the oak tree. My church is the river. My church is walking right down the cane field road, on the headland between rows of sugarcane. That’s my church. I can talk to God there as well as I can talk to him in Notre Dame. I think he’s in one of those cane rows as much as he is in Notre Dame.

Much of Ernest Gaines’s fiction was inspired by his childhood in Cherie Quarters. When Gaines was twelve, there were perhaps sixty people in the Quarters, housed in eight houses on one side, six on the other, with the church (which also served as a school) in the middle. All the houses in the quarters were identical, with two rooms that each had front and back doors; the tin roof also covered a front-facing gallery (originally the roofs were formed with cedar shingles). A central chimney with hearths in both rooms provided heat in winter and was originally used for cooking as well; later, the cooking was done on wood-burning stoves.

Clockwise from top left: Riverlake Plantation, Cherie Quarters, Mount Zion Riverlake Cemetery, and Mount Zion Riverlake Church (Riverlake Plantation and the Roots of Author Ernest Gaines, Faith Woods, theclio.com)

Ernest once described the cabin room where he was raised: “a wood-framed bed, a chifforobe, a washstand, and a handmade bench by the fireplace. . . . an oil lamp on the mantel. There were pictures on the mantel as well. The walls were bare, having been whitewashed many years ago. They were stuffed with moss and mud [bousillage], and when this broke loose the cracks were stuffed with either paper or pieces of rag.” There were only two books in the home: a Bible and an almanac.

In the nineteenth century, each room housed an entire family. By the time Ernest lived there, only one family used the building, so the rooms functioned as kitchen/living room and bedroom; outhouses were in back of the dwelling. There were no screens, so mosquito nets were hung over the beds at night; nor was there running water; buckets were used to fetch it from False River. Often cots were set up in the kitchen. Small families often only got one side of a house, or even one big room. Most families, however, were large; seven or nine children were not uncommon, such as in the nearby Domino and Hebert families, who had many children between them.

One of the cabins from Cherie Quarters can be viewed at the historic plantation home Magnolia Mound in Baton Rouge, quite near the LSU campus. All the others except one have been taken down, and this remaining structure is overgrown with vegetation and leaning on its foundation.

All the cabins in the Quarters had porches and functioned as communal gathering points. Here many of the tall tales, ghost stories, and gossip sessions that fueled Ernest’s imagination took place. In the summer, residents might build small outdoor fires with rags or leaves to keep the mosquitoes down. While porches were popular gathering places because of their shade and openness, Gaines notes that people “talked everywhere, especially around the fireplaces in winter.” There were also many social functions. Larger homes would sponsor suppers, featuring items such as gumbo, fried chicken and fish, potato salad and biscuits; customers would pay fifty cents for a plate.

On Voice and Dialect

According to Gaines, all his writing proceeds from a character’s voice: “Well, you first have to hear the voice, hear the voice of the character. Then I can see how to make that a child or an older lady or just a tough guy or somebody. . . . I have to get that voice and once I get that voice down, I said I can make it work.”

Gaines continually experimented, trying one method after another, until he finally hit, however, on the saliency of voice, a concept he always related to the musical. In an unpublished essay in the Gaines collection, he emphasized:

Music, music, music, there must be music around when I’m working, and when I’m not working … the most wonderful music instrument is the human voice. My characters must speak musically. My narrators must have a sense of rhythm. Not rhyme. Rhythm. The great thing about listening to a storyteller is not only what he says, but the way that he says it. In writing, I try to make you hear that storyteller.

He goes on to say that once he “caught the rhythm” of Miss Jane’s voice, the book unfolded naturally.

Cicely Tyson as the title character in the 1974 TV film version of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (dir. John Korty)

Gaines always saw form and language as intertwined and believed that dialect had to be presented in a form that was true to the speakers, but not demeaning. As he put it, “most of my characters have a dialect. But I create the dialect through syntax and the placement of words, not through misspelling. I also want my characters to be psychologically true so they’ll be as real as real people.”

On Voicing the Color Line

Veronica Makowsky: As these excerpts from Lowe’s biography concerning Gaines’s use of dialect illustrate, Gaines sensed and presented an intricately nuanced portrait of the color line through voices which distinguished class, ethnicity, gender, region, and generation, as well as race. Language as a means of communication enacts the fluid interdependence of the people of the South.

Gaines thought long and hard about how to present forms of Louisiana speech. . . . Gaines’s mastery of dialect was already superb in his early work. He not only distinguishes between white, Cajun, Creole, and Black speech, but also between the antique and the modern. In Gaines’ novel Catherine Carmier (1964), Brother, who is distributing mailed checks to the people, comically tells Miss Charlotte, “Check you later,” to which she replies, “I done told you ‘bout that ‘checking me’. . . . One of these days you go’n find something bouncing off that little steeple head of yours there.”

Brother, a modern man, has adopted slang parlance, and while Aunt Charlotte rejects it, she employs her own salty idioms in reply. If, as she claims, “that boy still playing with me there,” she is playing with him, too.

Like Faulkner, Gaines animates the narrative by crafting economical but pithy dialect, accurately rendering the peculiar syntax of Cajun speech and a sympathetic rendering of the always creative African American vernacular. Commenting on Brother’s announcement that his educated friend from California will arrive soon, François, a Cajun, asks Paul, “You think he one of them people . . . Them demonstrate people there.”

In The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, the proud Cajuns are distinguished by their class hostility more than by racism, and Gil Boutan, the star back on LSU’s team whose gridiron partner is Black, has definitely learned racial lessons from his athletic exploits, so much so that his grief over his dead brother is tempered by his dread of the coming racial apocalypse of revenge. His speech as rendered by Gaines even takes into account the effects college has had on Gil as compared to his father and the other members of the Cajun clan.

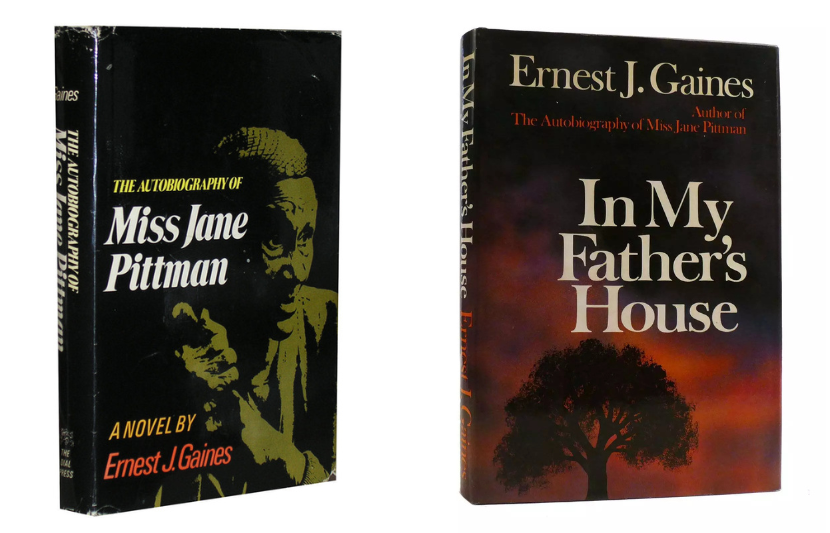

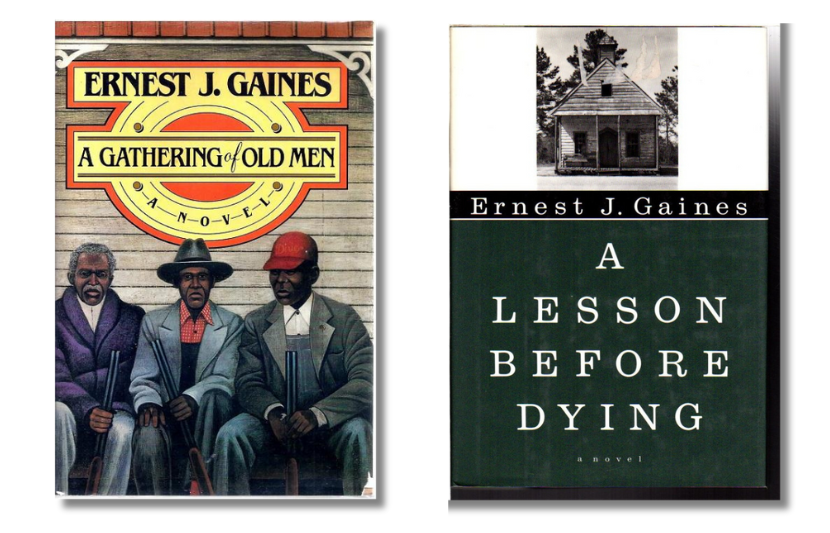

First-edition covers of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (Dial Press, 1971) and In My Father’s House (Knopf, 1978)

There are risks to giving every character an independent voice; in an interview, Gaines states he was told by a reader, “‘You gave life to the Ku Klux Klan. You made the Ku Klux Klan look good.’ But that’s something I would not have done. I just give them humanity. And of course, this came about by letting them show why they think as they do—as Faulkner did with Jason [a despicable character], say, in The Sound and the Fury.”

On Black Manhood

VM: In Gaines’s fiction, gender roles are inextricably linked to the legacy of slavery. As John Lowe explains in his biography of Gaines, the reverberations of slavery include the deleterious effects of absent fathers, the burdensome great expectations placed on promising young men, and the importance of “standing,” physically and metaphorically, despite the demands of a hostile white culture to kneel or collapse before it.

Ironically, Gaines based his model of standing on the moral strength and perseverance of his Aunt Augusteen, the disabled woman who raised him, and who metaphorically stood although all she could do physically was crawl. The intrepid Black women in Gaines’s fiction are usually the ones who enable a Black man to stand. Such moral dignity and courage are the universal qualities that Gaines valued across genders.

While the theme of manhood was very personal for Gaines [who was raised without a father present], he was also thinking of how prevalent this situation has been in African American culture, starting with the separation of family members during slavery, “the auction block,” and continuing through hard times when fathers often left to find work or to escape the guilt that came from not providing for their families.

In a 1976 interview with Charles Rowell, Gaines stated, “wherever the slave ships docked, families were separated. . . . Because of that separation they still have not, philosophically speaking, reached each other again.”

First-edition covers of A Gathering of Old Men (Knopf, 1983) and A Lesson Before Dying (Knopf, 1993)

Inevitably, such factors feed into an Oedipal narrative, where the sons seek revenge against their fathers. Even religion seemed to be unable to remedy this, which is perhaps why Gaines chose to make the central character of In My Father’s House (1978) a minister. As Gaines once observed, “I don’t know that the Christian religion will bring fathers and sons together again. I don’t know that the father will ever be in a position . . . from which he can reach out and bring his son back to him again.”

While Gaines often valorizes the search for manhood, he was not unaware of the perils of overemphasizing it. . . . Moreover, Gaines has been clear that his concept of “the importance of standing,” which, after all, he acquired from his disabled Aunt Augusteen (although associated with masculinity by most critics of his work), is actually “that moment in life when you stand. Manliness is that moment when it is necessary to be human—it’s that moment when you refuse to back down”; the time of such an epiphany can be brief, can occur in the span of a day.

On Religion and the Black Church

VM: To understand Gaines’s ambivalence toward religion, one needs to understand the role of religion in Gaines’s life as well as in his fiction, and even to consider the role of the novelist as a kind of moral inspiration like an effective preacher.

The church was in the center of the Quarters. Mount Zion brought people together for sermons, revivals, baptisms, marriages, and funerals, but also for award ceremonies and holiday pageants. Ernest told me of tolling the building’s bell to summon residents to last rites. Hard times and lack of adequate medical care often led to early deaths. Funerals were elaborate affairs conducted by multiple preachers. Almost everyone would be buried in Mount Zion Riverlake Cemetery; if money was scant, the graves went unmarked. Ernest’s most moving fictional rendition of the latter comes in A Lesson Before Dying, where the entire community assembles in the school for a dramatization of the birth of Christ.

Ernest himself was never a churchgoer as an adult; however, in a PBS documentary that I participated in, he went on record as being a religious person. On another occasion, he stated, “My church is the oak tree. My church is the river. My church is walking right down the cane field road, on the headland between rows of sugarcane. That’s my church. I can talk to God there as well as I can talk to him in Notre Dame. I think he’s in one of those cane rows as much as he is in Notre Dame.”

Ernest J. Gaines Black Heritage stamp, issued by the United States Postal Service in January 2023 (usps.com)

By the time Ernest and his wife, Diane, built their new home near Cherie Quarters in 2004, the church at Cherie Quarters had become dilapidated. . . . Ultimately, however, the couple rethought that and realized that the building should be restored to its original form and that it could function as a type of museum. . . . Showing Melanie Warner Spencer the restored church in 2018, the year before he passed away, he declared, “Except for my home, it’s the most important building in the world.” He often told visitors that inside the church, he hears the voices, the songs, and the stories of the old people who have continually inspired and nourished his art.

In A Lesson Before Dying, the white power structure regards Grant, the schoolteacher, with deep suspicion; he has, after all, broken away from the circle of surveillance, and worse, during that time, has acquired an education, which is tacitly understood to mean mastery of techniques of resistance. As long as he can be confined, however, to the narrowly tolerated and barely nourished Black school, a school necessarily inscribed within the Black church (an institution, with its white God and “servants obey your masters” Bible, felt to be helpful for social control—at least up to the civil rights movement), Grant can be tolerated as a necessary evil.

Reverend Simmons, in the short story “A Long Day in November” (1957), is one of a long line of ineffectual preachers in Gaines’s work. His negative characterization of preachers only finds a reversal in the positive portrait of Reverend Ambrose in the late novel A Lesson Before Dying. The novel In My Father’s House (1978) brought to a head all the complex and contradictory feelings Gaines had about preachers and the African American church.

He had been baptized himself in False River with many of his friends at the age of twelve, but he was never keenly religious and more or less abandoned his faith after he returned from the army to San Francisco. Still, he respected the strengths of the church, and as we have seen, made it an important element in Miss Jane’s story.

Gaines must have been aware, however, of the moral impetus in many of his works and how his dedication to the people paralleled that of many Black preachers. Indeed, his childhood friend Ben Biben commented on how everyone in the Quarters knew E.J. would succeed, since, after all, he was “the one” to all of them, and that “he was always with us,” and “he should have been a preacher!”

However, Ben also said, on the other hand, that E. J. was “kind of devilish,” and he liked those sinful blues too much.

Portrait of Ernest J. Gaines (biblio.com)

John Wharton Lowe (1945–2023), Barbara Methvin Professor of English at the University of Georgia, was the author or editor of ten books, including Jump at the Sun: Zora Neale Hurston’s Cosmic Comedy; Calypso Magnolia: The Crosscurrents of Caribbean and Southern Literature; Conversations with Ernest Gaines; and Approaches to Teaching Gaines’s The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and Other Works. He served as President of the Society for the Study of Southern Literature, was Senior Fulbright Professor at the University of Munich, and was a past president of MELUS. He was formerly at Louisiana State University as the Robert Penn Warren Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature and Founding Director of the Program in Louisiana and Caribbean Studies. His authorized biography of Gaines, excerpts from which appear above, is forthcoming.

Veronica Makowsky is Professor of English Emeritus at the University of Connecticut. Her books on Caroline Gordon and Susan Glaspell are published by Oxford University Press, and her recent book on the novelist Valerie Martin is published by Louisiana State University Press. She is the author of numerous articles on American women and southern writers such as R. P. Blackmur, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Nelson Page, Kaye Gibbons, Stark Young, William Faulkner, Walker Percy, Edith Wharton, Margaret Atwood, Eudora Welty, Janice Holt Giles, Margaret Laurence, and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings.