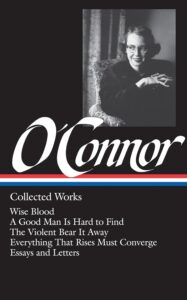

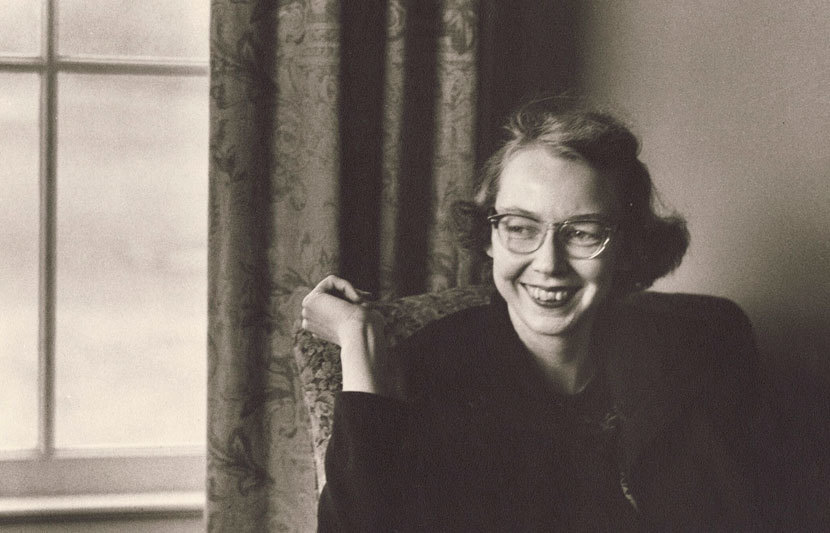

Flannery O’Connor’s Why Do the Heathen Rage? by Jessica Hooten Wilson (Brazos Press, 2024; photo credit: Andrea Barnett)

Flannery O’Connor died in 1964 at the age of thirty-nine, having published two novels and dozens of short stories that would cement her reputation as one of the American South’s most revered literary voices. After her final story collection, Everything That Rises Must Converge, was released posthumously in 1965, an unfinished novel, titled “Why Do the Heathen Rage?,” remained tantalizingly archived in folders at Emory University in Georgia. Only a short excerpt of the novel had appeared during her lifetime, in a 1964 Esquire feature labeled “Works in Progress.”

Had O’Connor lived, there’s little telling how this work might have turned out. Scholars who attempted to sort through the unpublished material found, in the words of one, “only an untidy jumble of ideas and abortive starts, full scenes written and rewritten many times, several extraneous images, and one fully developed character.”

In her recently published book, Flannery O’Connor’s Why Do the Heathen Rage? A Behind-the-Scenes Look at a Work in Progress (Brazos Press, 2024), author and scholar Jessica Hooten Wilson attempts to unravel this textual mystery, giving shape and context to the fascinating fragments O’Connor labored over in the last years of her life. Centered on Walter Tilman, a listless young man beset by illness and living at home on his family’s farm, the “Heathen” typescripts hint at revelatory new directions O’Connor may have taken in her fiction, from issues of racism and social justice to her own faith and physical deterioration.

Below, Hooten Wilson speaks with LOA about her deep dives into O’Connor esoterica, the bold artistic innovations contained in the uncompleted novel, and how to think about the author’s evolving viewpoints on the central moral and political questions of her time—and, indeed, of ours.

O’Connor in the driveway at Andalusia, her Georgia estate, in 1962 (Joe McTyre / AP Photo / Atlanta Journal-Constitution)

LOA: How did you first learn about “Why Do the Heathen Rage?”

Jessica Hooten Wilson: I found out about it from O’Connor’s friend and biographer William A. Sessions. I was exploring the Dostoevskian connections in O’Connor, Dostoevsky being someone who’s also writing in a world where God is dead. Sessions saw what I was doing with Dostoevsky and said that O’Connor’s most Dostoevskian work was “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” But she hadn’t finished it.

That year, I headed to O’Connor’s archives at Emory University in Georgia. In the 1970s, they had put everything that looked related into folders, so it’s not something O’Connor organized herself, which means there’s a lot of guesswork. Folders 215 through 234 are dedicated to what O’Connor was working on at the very end of her life, titled “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” As a scholar, I was thinking I’d take this material, try to figure out what O’Connor had been doing with it, and share the path I thought she was on.

Eventually I published an article and gave a presentation at a conference. In the audience were Louise Florencourt, who was O’Connor’s cousin and the executor of her estate, as well as Sessions. Both of them were taken with what I saw in the work and how I understood the unfinished materials. Only two or three other scholars had ever written anything on it, and what I was doing seemed a little different.

LOA: Because there’s seemingly no way to construct a complete book out of the existing material, previous scholars didn’t think it constituted a substantive part of O’Connor’s oeuvre. But you disagree with that view.

JHW: You can’t sit in front of these 378 pages and say, “This is a novel.” The novel isn’t done; in fact, it barely gets started. So if you’re looking for something like Ralph Ellison’s unfinished second novel, Three Days Before the Shooting…, where there is enough material to put together a manuscript, O’Connor just didn’t give us that.

But the question is, what do we have and is it worth reading? That’s a separate question, and that’s where Sessions and I started to go. Sessions’s original idea was that he could potentially include the material I was working on in the biography of O’Connor he was writing. To have these unpublished materials be part of this larger whole would help tell her full story. But Sessions died before publishing his biography, unfortunately, so we missed out on that opportunity. [Editor’s note: As of 2024, Sessions’s biography of O’Connor remains unpublished.]

Next, I was encouraged to try ghostwriting the unpublished material into a novel, which was really fun. Fan fiction is a great opportunity because it makes you pay more attention to the writer’s use of diction and syntax and imitating voice. But it wasn’t O’Connor, and you could never publish it and say it was a finished work. Instead, I had to find a different way to tell the story that made it a beneficial reading experience and not a disappointment to those who are looking for a cohesive novel.

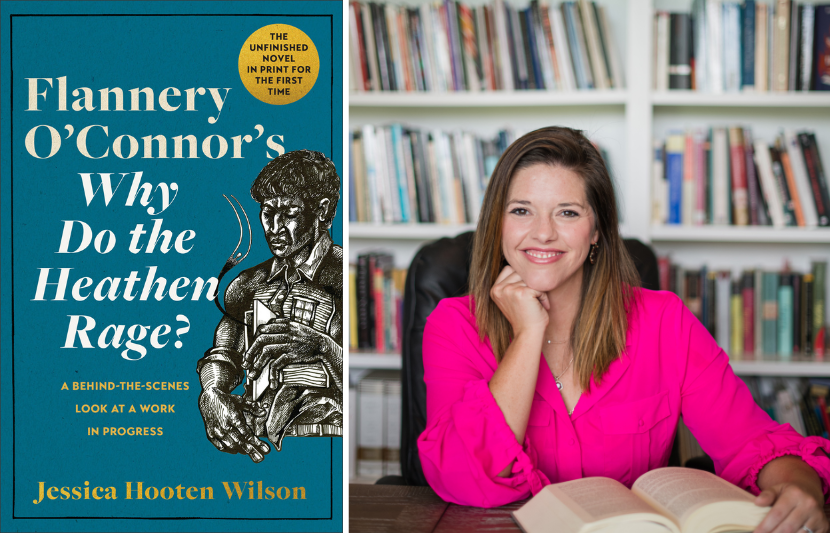

First-edition covers of O’Connor’s published books: Wise Blood (Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1952), A Good Man Is Hard to Find (Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1955), The Violent Bear It Away ( Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1960), and Everything That Rises Must Converge (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1965)

LOA: What did you find in the archive, and what did it tell you about O’Connor’s life and writing during her final years and months?

JHW: Going through it, you have scene after scene of seemingly related material where O’Connor is messing around with the same characters and the same small world and the same layout between the Tilman family farm and the would-be social reformer Oona Gibbs in New York. There’s a loose connection between things, but no arc that says what each character is going to do or how they’ll develop.

O’Connor’s writing process was that she would get up every morning and work from nine to twelve, and if she couldn’t think of anything new, she would just retype the pages from the day before and make adjustments to them. She was always reworking material, so we have a lot of repetition, with maybe fifteen separate episodes that occur.

A lot of times, you have, for example, the word “girl” crossed out and replaced with “woman” on one page, and then on another page, in a different folder, “woman” crossed out and replaced with “girl.” There’s no way to tell which version of each sentence she ultimately wanted.

Cover of the July 1963 issue of Esquire in which an excerpt from “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” appeared (esquire.com)

LOA: One thing that struck me was the extent to which the “Heathen” material got parceled out to O’Connor’s other novels and stories. There’s the passage that appears in The Violent Bear It Away, the origins of the narrative in “The Enduring Chill,” and of course the excerpt she published in Esquire labeled as a work in progress. Why would she have chosen to break her work apart in this way?

JHW: I don’t think it’s uncommon for writers to publish small pieces from unfinished texts to share glimpses of what they’re working on. As for the appearance of “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” in Esquire, they were asking for an excerpt of an in-progress book, so you don’t have a complete short story with the snippet that she publishes, and she wasn’t intending for it to be that. Compare that to Wise Blood, which actually is a novel sewn together from short stories—almost the reverse of “Heathen.”

From my perspective (and some scholars may disagree with me), when O’Connor faints in November 1963 from her illness, lupus, I don’t think she returns to the novel of “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” The short stories we see published afterward—”Judgment Day,” “Parker’s Back,” and “Revelation”—are what she works on instead during the last six to eight months of her life.

She really didn’t think she was going to live in the first half of 1964. She takes the last sacraments a month or so before she dies. At one point, she even writes a letter to her editor that says, in essence, “I’m going to pass away before Everything Rises Must Converge, the collection, will be published, so just publish the stories as they are. I don’t have time to work on them.” She knows that she’s not going to finish the novel, so she extracts sections from “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” and publishes them as “Parker’s Back” and includes sections in “Judgment Day.”

Andalusia Farm in Georgia, where O’Connor lived from 1952 until her death in 1964 (Stephen Matthew Milligan / CC BY-SA 3.0)

LOA: You make a case that O’Connor, in this novel, is dealing with themes or characters that are new in her fiction. What kind of a departure would “Heathen” have been for her?

JHW: There’s a few things that are very striking in this work in progress. First, O’Connor usually has a trajectory for her main character in which one moves from a place of blasphemy or demonic possession to receiving or rejecting a moment of grace. If you look at her novels, in Wise Blood, Hazel Motes moves from the Church without Christ to becoming an ascetic holy fool. If you look at Francis Marion Tarwater from The Violent Bear It Away, he goes from wanting to be his own person, even if it means demonic possession, to becoming a prophet.

In “Heathen,” O’Connor wanted to start with the conversion of her main character. The conversion in previous O’Connor works happens with a violent intrusion into the narrative: her characters get hit over the head with a psychology textbook or get shot in the chest by a serial killer. Instead, with “Heathen,” she wanted her character to hear this “so small voice of God,” is what she says. So you have Walter Tilman sitting on a rock, reading and thinking about all these things that he’s read, and realizing, only intellectually, that he believes in God. That’s the opening conversion, and it’s very unlike O’Connor’s other work.

O’Connor holds up a mirror to the reader and asks, ‘In what ways are you being two-faced? In what ways are you being a hypocrite?’ And look at what can happen in the world around you if you are not actually walking the talk, so to speak.

She may have been inspired by the Catholic novelist J. F. Powers, who wrote her a letter and said, “Stop killing off your characters. The best stuff happens after the conversion.” After reading Powers’s letter, when she writes the short story “The Enduring Chill,” she keeps the main character alive for the sole purpose of watching him take on a new form and become a holy character. She’s asking what that might look like. To me, it’s like Dostoevsky’s The Idiot or Alyosha Karamazov, and it would have been amazing to see.

There’s also the hint of a love relationship in “Heathen.” Colleen Warren is a scholar who’s done more work on that. She and I corresponded during this project, because she had seen the “Heathen” manuscript and she mentioned that there was a romantic relationship there, where Oona Gibbs and Walter Tilman would have maybe gotten married or fallen in love or had an affair. O’Connor had never done that before in her fiction.

O’Connor in 1952 (APIC / Getty Images)

Finally, the most obvious new theme O’Connor tackles in “Heathen” is race. O’Connor lived in a time when the United States was segregated—the Civil Rights Act was signed only a month before she died. And even when buses became integrated, it took her five years to dwell and meditate on what was happening. She was trying to do that in order to produce art, because she never wanted to merely react to her time. She always wanted to dig down underneath things, she says in her prayer journal. She wanted to dig underneath the surface of the headlines to find out what was happening with people, really dig into the human soul and its responses. I think one of the reasons we can publish this text now and still get something from it is because she tried to do that difficult work of digging to get to the more eternal things happening.

LOA: Speaking of race, in the unfinished novel, the main character writes letters in the guise of his father’s Black servant, a phenomenon you term “literary blackface.” Some scholars have argued that O’Connor’s views on race are disqualifying, or at least present an insurmountable barrier to reading her in good faith in the twenty-first century. What is your take on the question of interpreting an author’s racism when that person is also a product of a specific time and place?

JHW: When we look at writers of the past, there are two approaches when it comes to assessing their blindnesses. If we look at Dostoevsky, for example, he was anti-Semitic and had no problem with his anti-Semitism. We still want to read Dostoevsky. We’re not going to take that part of who he was when we read him and uplift it—that’s the part that we can cut away from and say, “That was blindness. That was wrong.” But his insights into the nature of suffering and immortality are timeless, so let’s hold on to those things. Let’s find the gold that is there and get rid of the dross. That’s one approach.

Then look at Flannery O’Connor in parallel. She does not uplift racism the way that Dostoevsky uplifts anti-Semitism. She found her white society’s views as problematic. She would always write very candidly in her letters, for example, about Dorothy Day, “I hope that to be of two minds about some things is not to be neutral.” She’s really struggling with the fact that she wants to uplift Day’s charity and moves toward equality and integrated racial fellowship. But at the same time, O’Connor is asking, “Who is Day? Is she coming down from the north and interfering with us? Why can’t we do things gradually?” To which most of us today would reply, “Because it’s been long enough. There is no gradual integration.” So we can see that problem in O’Connor’s life, but she admitted the ambivalence.

Crucially, O’Connor doesn’t write in a way that downplays Black Americans. The characters who do see Black Americans as unequal usually get slapped in the face by how wrong they are. If they are dehumanizing other people, they get what’s coming to them. I think we need to ask, “Did O’Connor think racism and segregation were a good in society?” We have to be able to discern these things in her work and handle them with nuance and generosity. When people are certain about exactly what’s right or wrong in every circumstance, there’s an arrogance there that can feel dishonest. Compare that arrogance to O’Connor’s style, which to me seems to be constantly seeking that her art be above her own human limitations. I find it refreshing to see someone able to admit their faults and try to move through them to a higher place in their art.

What I found in O’Connor was a necessity to actually practice what you believe. She regularly says that your beliefs, your words, and your deeds should be one. Very Kierkegaardian, in that sense. O’Connor holds up a mirror to the reader and asks, “In what ways are you being two-faced? In what ways are you being a hypocrite?” And look at what can happen in the world around you if you are not actually walking the talk, so to speak.

O’Connor in an undated photo (Emory University Archive)

LOA: Throughout your book, there are asides where you imagine O’Connor in her day-to-day life, and then there’s the section where you attempt to construct a concluding episode for “Why Do the Heathen Rage?” Could you talk about the more creative aspects of your project? How do you pick up an author’s work after they’ve set it down?

JHW: I know that it was presumptuous, so that’s why I quote Angela Alaimo O’Donnell that all great art should be presumptuous. My attempts at creativity and response, they’re not nearly as strong as O’Connor’s writing. But what I was trying to do is put them out there in a vulnerable way and say, “I think we should have art that responds to her work, art that keeps her in the conversation.” And some of the best art in the world has been in conversation: Dante responding to Virgil, Dostoevsky responding to Dickens and Poe. I think we need to make sure that O’Connor is part of that tradition.

Jessica Hooten Wilson is the inaugural Visiting Scholar of Liberal Arts at Pepperdine University in Malibu, California. She previously taught at the University of Dallas. She is the author or editor of eight books, including Reading for the Love of God, The Scandal of Holiness (winner of a Christianity Today 2023 Award of Merit), and Giving the Devil His Due: Demonic Authority in the Fiction of Flannery O’Connor and Fyodor Dostoevsky (winner of a 2018 Christianity Today Book of the Year Award). Hooten Wilson speaks around the world on topics as varied as Russian novelists, Catholic thinkers, and Christian ways of reading.