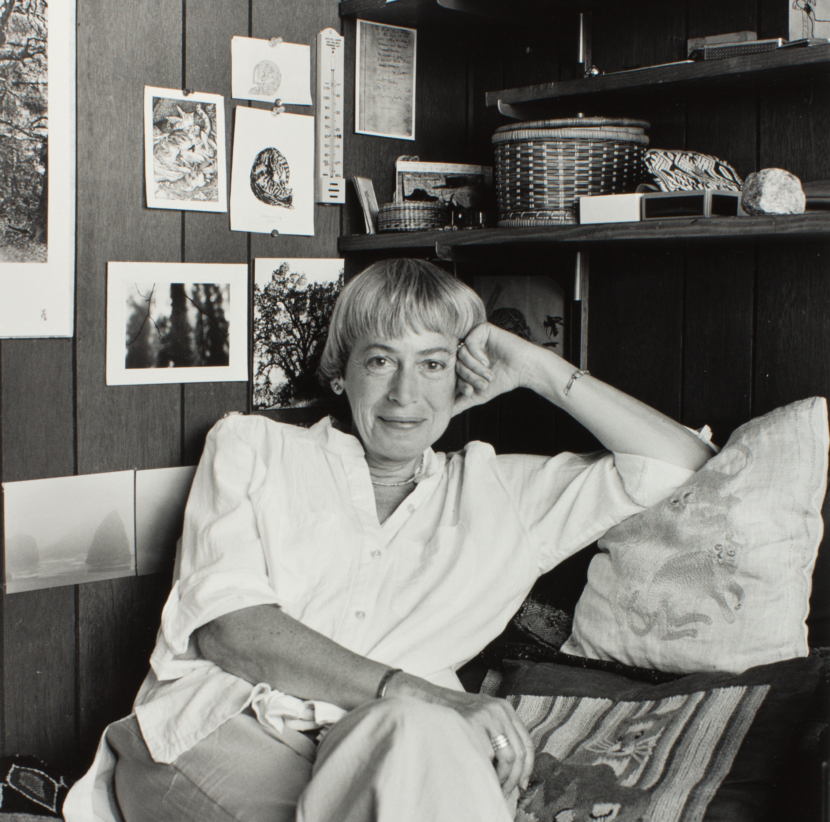

Arwen Curry and Ursula K. Le Guin (Courtesy of Arwen Curry)

When taking in the sheer scale of Ursula K. Le Guin’s literary accomplishment, it can be hard to remember that she was also a real person in the world: wise, grounded, sure of her immense talent yet always open to the new and unfamiliar. It’s this unguarded side of the author that we get a rare glimpse of in filmmaker Arwen Curry’s exceptional documentary, Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin (2018), and her follow-up series of short films, “The Journey That Matters,” which debuted on LitHub this fall.

Over the phone, Curry spoke to LOA about the evolution of her decade-plus project, the challenges of conveying the feeling of reading a book through the medium of film, and the time Le Guin served her elk for dinner.

LOA: What initially drew you to Le Guin as a subject, before you started working on your 2018 documentary? What was your connection with her work?

Arwen Curry: Le Guin’s novels were on my family bookshelf growing up and I read them. They were part of that back-of-the-mind library that informed my own creative first steps. I was drawn to Le Guin as a subject for a film because of the parallels between her biography and my own family’s biography, which are not that striking on the surface, but there was something about the tone of her work and her tone as a human being, once I got to know her, that was very familiar to me.

I think it was because, like Le Guin, I had a scientist father, but also, thanks to both my parents, a very creative household that fostered imaginative play and imaginative work. My father was an early Dungeons & Dragons guy, so he would invent his own worlds and his own cities, and my brother and I would adventure through them, sometimes just talking through these fantastical places.

When I read Le Guin’s books as a kid—A Wizard of Earthsea and The Lathe of Heaven were the first—that was a familiar way for me to move in my imagination. I felt a kind of opening, a connection between the creative act that she was participating in and that I was interested in, and the way that magic was used in her world of Earthsea and the archipelago. I mean, I’m named after an elven princess from Tolkien. I felt at home in that kind of place. Even though I never was a diehard science fiction or fantasy person per se, it was still a very rich way to approach the world.

I think what I wanted from speaking with her—why I wanted to make a film rather than write a book—was something that occurred to me in my young twenties after I had gone with my best friend to see Adrienne Rich speak. Kat and I were talking about how different it is to be in the room with a writer that you admire, to hear their cadence and to be in their physical presence. And I thought, that’s what I want to do. And who’s the person I want to hear from, to see? It immediately came to mind—just the personal connection, the richness and relevance of her ideas—that it was Le Guin.

The fact that she spoke with me and gave me this opening into her life was very generous—and lucky. It was just a moment when she had the willingness to do that. It was maybe naive of me to think that she would agree to do it, but I was lucky enough that she did.

Ursula K. Le Guin at her home in Portland, Oregon, during the filming of Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin (Courtesy of Arwen Curry)

LOA: You worked on Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin for almost a decade, is that right?

AC: I was coming out of editing what was known as the Bible of punk rock zines, Maximum Rocknroll, and when I felt like I needed to move on, I went to journalism school. It was a two-year documentary program at Berkeley that I entered specifically to learn how to make this film. After I graduated, I approached [Le Guin] and started the project with her blessing. I began trying to fundraise while also building up my career, learning about how to make a documentary by working on other projects.

A lot of that ten years was just doing what documentarians do trying to raise money. Unless you have independent wealth or financial backers, it’s a painstaking process to raise money from grants and other methods. That took a while, and then other things happened in the meantime. I was coming into my adulthood, going through rites of passage, having babies, and every one of these things put a delay into the project, which Le Guin was very gracious and tolerant of. It always seemed like something was dragging the project down, like, “Wow, we’ve got to finish, we’ve got to move faster!” There were long periods when it felt like it was stalled, the money had stopped, or things weren’t coming together.

When you’re filming, it’s always kind of heightened. You’re on and your entire crew is on because you want to capture everything through the lens of the camera. But there are all the in-between parts as well, and she and I spent a lot of time talking.

But then eventually it did come together, and in the end, I’m grateful about that long, protracted process of production because it allowed for a really natural trajectory, which was not only in the film but in Le Guin’s life and in the perception of her in the literary world and in the public eye.

When I started the film in 2008, I still had to explain to a lot of people who she was. That would still occasionally happen toward the end of the film, but she really had, in the last few years of her life, entered the literary canon in a way she hadn’t before and finally broken out of that silo that science fiction is contained in in the publishing world. There was enough of a groundswell of recognition through Library of America and other means, including the National Book Award and so on, that people began to understand, OK, yes, she’s from the West Coast, yes, she writes in genre fiction sometimes, yes, she’s plainspoken and open to speaking with people, but she’s also one of our greats. I loved being able to have that arc in the film and have it be genuine.

Ursula K. Le Guin and Charles Le Guin during the filming of Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin (Courtesy of Arwen Curry)

LOA: How did she react to this shifting perception around her career and her work? Was she aware of it? Was that part of your discussion as you worked on the film together?

AC: I don’t know that I became aware of that arc until the last few years, but it was something she was certainly aware of, because a lot of it really was material. It was options for films that were being sold, it was new editions and new collections of her wonderful essays and short stories, which really had been coming for a long time—beautifully bound editions and reprintings and so on. Her work was reaching different countries, it was reaching many more people. It was a virtuous cycle where the more she was getting out there, the more people became aware of her.

Younger readers began to be very interested in her. They always had been, with her young adult literature, but I think new generations of speculative fiction fans and younger BIPOC readers were understanding her work as kind of a godmother of these speculative spaces in which liberation could be achieved in all kinds of interesting, creative ways. She was very cutting-edge in that sense.

There were a few other writers when she came on the scene in the early ’60s that were doing that, who were beginning to take a cue from the soft sciences and write things that were more ethnographic, more psychological, and just more human than a lot of the hardline science fiction at the time. But she always had the stance that what she was doing was real literature, and that real literature could happen in science fiction and in fantasy. She never disavowed science fiction and fantasy, but she put pressure on her fellow writers to elevate their work, to write at their best, and she put pressure on the publishing industry to recognize what was good there for being as good as it was.

Ursula K. Le Guin in the early 1950s (Courtesy of the Ursula K. Le Guin Foundation)

LOA: In a talk you did with Public Books, one thing that came up was Le Guin’s relationship to feminism: how she didn’t initially identify as a feminist, but as she became more connected to the movement, her writing became a way to work out these ideas, test out questions of politics or identity or other things that were active in the culture. But she did it in an idiosyncratic or personal way that was maybe less doctrinaire than what people typically think of as “political writing.”

AC: It was about working it out through the work. It was not an end point. It was a process in which she was learning to perceive herself differently, to perceive herself as a woman in different ways and as a feminist. This is kind of the arc of the documentary, this shift in perception, which I really think is what kept her going and kept her so prolific. We have that openness of mind to thank for all of the wonderful work she continued to create throughout her life.

Right now, I’m reading the Earthsea books to my two sons, who are eight and six. We read the first three, and I thought we might wait a while before we read the fourth one, because there was this long period of time in between the third and the fourth book, and Le Guin had a lot of changes happen in this time, and there’s also some more mature, scarier themes. But they said, “No, no, let’s go ahead.” So, I’m reading Tehanu out loud to them, and it’s such a rumination on power, on female power, on women, the ways that women have tried to access the world of male power and the ways that they’ve resisted it. And it’s very much a rumination on feminism within the story, within the same world that she gave us initially, which she doesn’t turn away from or change in a fundamental way. She just turns the camera, and it’s brilliant.

Ursula K. Le Guin in Napa, California, during the filming of Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin (Courtesy of Arwen Curry)

LOA: Can you talk about the genesis of your new film project, “The Journey That Matters”? Was this something you had in mind toward the end of your work on Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin?

AC: The footage that didn’t make it into the film was nagging at me, because I knew that she was gone, and I missed her, and her fans and her readers missed her. And there were other insights into her personality and her process that were in this footage that I wanted to make available.

I began having conversations with Ursula’s son, Theo, who manages her estate, and saying that I had this footage and was wondering what could we do with it. “The Journey That Matters” sort of started with a brainstorm between Theo and me about what stories we could tell, seeing which pieces were not necessarily told in the film. I wanted to share those, and I was hoping, and still hope, that they can be useful to viewers and organizations who could use that boost from Ursula, use that information about her beliefs and her way of being in the world. I think that’s something that we all, that everyone who loves her as a reader, is eager for more of.

LOA: How did you land on the six themes explored by the series? They’re all distinct but seem to touch on questions that are very much in the public consciousness right now, questions about reproductive rights, questions about racism. What types of stories did you think would lend themselves to this type of short-form video?

AC: I think one way of approaching it would have been to open up more of her life, her intimate life, to people who already care about her, who might want to know what her desk looked like, or what was her relationship like with her husband. And then the piece about her writing characters of color and the piece about the abortion she had as a young woman are more tied in with social themes that we’re all dealing with. And of course they are personal as well.

When I initially put this together, we had a much longer list and winnowed it down to what we thought would be the strongest. But there’s more to go through, and I’m hoping that there will be more videos down the line. Some of the things we weren’t able to cover will still hopefully make it out into the world.

Ursula K. Le Guin at Radcliffe, 1950 (Courtesy of the Ursula K. Le Guin Foundation)

LOA: Given the surfeit of material that you had, and the length of the project, do you have memories of working with Le Guin, or things that passed between you that you didn’t include in the film? Are there moments or experiences that come to mind as especially meaningful for you?

AC: Oh yeah, I think about moments with her quite a bit. When you’re filming, it’s always kind of heightened. You’re on and your entire crew is on because you want to capture everything through the lens of the camera. But there are all the in-between parts as well, and she and I spent a lot of time talking.

We had dinners—she served me elk once—and conversations where the camera wasn’t on. Those are probably the most meaningful to me, and it has to do with that presence that she had, which was at the same time warm and welcoming and human. And she’s a moral and an intellectual giant, so her mind was always working, and yet on some level she was always with you there in the room as well. She was fully aware of her worth and of her gift. And I think she considered her writing to be what she had to do, both for herself and for the world. It was what she was meant to do, and I think she was right about that.

Many people are making films about writers who are no longer with us, but she was able to narrate the work that’s excerpted, describe parts of the work—what the islands look like, how magic works there—in her own voice.

But on a human level, she had no desire to elevate herself above anyone else. When I would come with the crew, she would always introduce herself to everyone and ask them about their craft. She was interested in other people, in ways of understanding the world, in science and politics, in the work of other writers, right up until her death. And although it’s hard to live up to that kind of standard, to have that as a standard, I am very glad that I do, not only in a distant way, but in a personal way. Because it gives me something to aspire to, to measure goodness against. To sort of ask, well, what would Ursula do in this situation?

I think that’s there for everyone. It was enhanced for the people who were fortunate enough to know her as a friend, but it’s there in the work, too. She is the person she presents herself to be in her essays, and if you read her essays, that’s the same kind of tone, the same kind of feeling that she left you with as a person—except sometimes sillier and more mischievous.

She was someone who liked to have fun and was affectionate and also human. She was cranky sometimes. She could be pretty strict, pretty harsh if she had a judgment about something. She didn’t suffer fools, and she didn’t suffer foolish actions even by people she didn’t consider to be fools. It wasn’t all home-baked bread or whatever, but she had a unique combination of traits that I’ll carry with me in my memories, always.

LOA: What are the challenges of translating literary life and writing to the medium of film? How did you try to evoke the feeling of reading Le Guin’s work for viewers, when the experience of watching cinema is inevitably so different from encountering language on the page?

AC: That’s a central challenge to anyone making a film about a writer. I’ve worked on films about visual artists and musicians, and in those cases, well, you obviously show the work in some interesting way. It may be unexpected, but you have it there so the viewer can have an immediate, direct connection with the art.

With novels you can put tiny pieces in, excerpts, bits of words or poetry, but you are also going to have to try to convey the overall experience of reading that work to someone who hasn’t read it while also doing justice to it for the people who know it very deeply. So that was a big challenge from the beginning and I came at it from different angles at different times. How would I represent these worlds? How would I represent the places in the books that we had to go to in order to understand why the books resonated with so many people?

There was a time when I thought, well, I can’t. It’s too audacious to try to represent this work visually with new art, so I’ll just use imagery from the natural world. But there needed to be something where you could really go into the Tombs of Atuan, where you could really step into the darkness. It needed to be more explicit and more narrative, so we did end up using animation and I think it worked really well. It was a challenge to figure out how to do that and it did feel very daring.

Le Guin was still alive when we were working on that imagery and I was so fortunate to have her. Many people are making films about writers who are no longer with us, but she was able to narrate the work that’s excerpted, describe parts of the work—what the islands look like, how magic works there—in her own voice. I love that and I think it gets you there emotionally much faster than if it were another narrator or just words on the screen.

Another thing that helped with the storytelling was having other writers talking about how the work made them feel when they read it. With Neil Gaiman and Michael Chabon, you’re hearing about the impact that Le Guin had on them as young writers, and so that helps you see the spark she set off in people, like that moment when you connect to an artist that is going to change your life or change your practice from that point on.

Ursula K. Le Guin, 1988 (Marian Wood Kolisch)

LOA: Which are your favorite books of Le Guin’s, and what would you suggest as someone’s introduction to her? Also, any lesser-known books you’d recommend to her existing fans?

AC: Really the best answer is that it depends on you, because she covered so much ground. If I were wanting to read something of hers but didn’t know what, I’d probably go to her website and play around and see what stuck out to me. Some people who are more politically minded gravitate toward The Dispossessed—that’s a very important novel for a lot of people. The Left Hand of Darkness, of course, and the Earthsea books.

For lesser-known works, The Wave in the Mind is a book of essays that I adore, and some of her later work that I think David Mitchell called “autumnal” in the film. There’s a book called Four Ways to Forgiveness [republished as Five Ways to Forgiveness by LOA] that’s absolutely devastating and beautiful. And then if you want a quick primer on how deftly she creates different worlds, Changing Planes is really fun. It’s just a few pages per story and each one is wildly different: a different world, different adaptations to the environment, different kinds of people facing different problems. It’s like she’s showing off, showing you what she can do.

Arwen Curry worked with Ursula K. Le Guin for ten years to create the award-winning documentary Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin, which was nominated for a Hugo Award and broadcast on PBS American Masters. Her short film series about Ursula, “The Journey That Matters,” is available on LitHub. She has worked on films including EAMES: The Architect and the Painter, American Jerusalem: Jews and the Making of San Francisco, and Regarding Susan Sontag, among other projects. Curry is a former chief editor of the punk magazine Maximum Rocknroll and has written for print, radio, and film. She is currently developing a documentary about the promise and challenges of intentional communities in America. She lives in San Francisco.