This September, Library of America published Adrienne Kennedy: Collected Plays & Other Writings, gathering the powerful, dreamlike works of a peerless American playwright on the occasion of her 92nd birthday. Below, Ariana Pettis, LOA’s inaugural Diverse Voices Editorial Fellow, discusses the through-line of love connecting Kennedy’s craft across genres and decades.

Adrienne Kennedy in the 1980s (Criterion / Adrienne Kennedy)

Adrienne Kennedy knows so much of love. At the start of my editorial fellowship at Library of America in 2021, I read her groundbreaking autobiography, People Who Led to My Plays, and was amazed by her reverence for the world around her.

First-edition cover of People Who Led to My Plays (Alfred A. Knopf, 1987)

Like the treasured scrapbook Kennedy’s mother kept, “recording wonders” between its red covers, People Who Led to My Plays collects “wonders” spanning almost thirty years: psalms, family memories, comments on the news, reflections on historical figures, Kennedy’s favorite things from high school, and even tributes to artists she adores, from William Wordsworth to Nat King Cole.

My favorite “wonders” that Kennedy shares in the text, however, center around her and her mother:

Adrienne Ames (my mother and my name):

My mother often told the story of how when she was pregnant she went to a movie and saw Adrienne Ames and decided to name me for her. How could I see then that my name was responsible for inspiring in me a curiosity about celebrity and glamour?

My mother and her hair:

When my mother cut her hair I used to beg her to let me keep the strands.

My mother and my face:

My face as an adult will always seem to be lacking because it is not my mother’s face.

People in my mother’s dreams:

People whom my mother saw at night had often “been dead for years.” I didn’t know anyone who had been dead for years. So her dreams held a spectacular fascination. “My Aunt Hattie,” “my stepfather,” “my grandmother,” “my mother,” all were people who had been dead a long time. But from my mother’s dreams, I got to know them. They all were from Georgia. They were all from the town my parents were born in, Montezuma.

In these excerpts, we see Kennedy offering her love and wonder to the reader, and a similar tendency extends throughout her oeuvre. Even her poetic stage directions make apparent the admiration she feels for life. In Diary of Lights, she writes:

The dialogue is collective and almost a song.

Their whole youthful summer is a dance and the dances all reflect this.

In Black Children’s Day:

The children are not realistic . . . but are like the memory of childhood . . . endearing, innocent and very serious.

And in He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box:

MUSIC

The song “See See Rider Blues” runs throughout the play.

It is the motif of this world.

The Ma Rainey version I heard as a child, summers in Georgia.

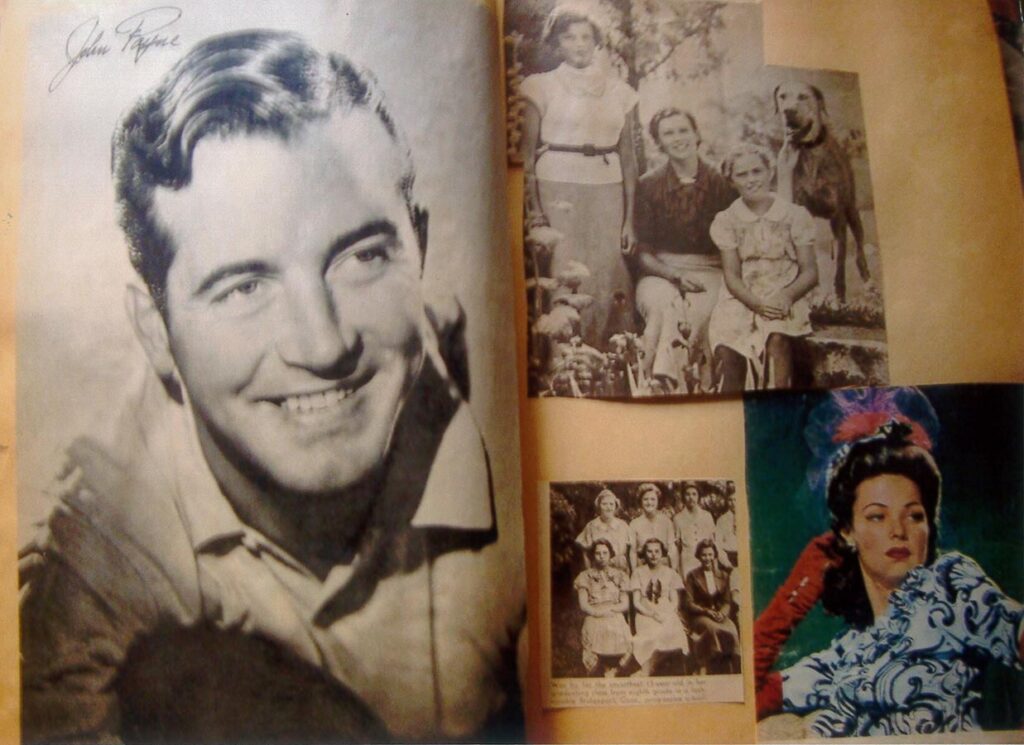

Excerpt from Kennedy’s homemade scrapbook (Criterion / Adrienne Kennedy)

In both plays, the fractured identities of the central characters exemplify how the violence and absurdity of racism harm the mind and body. At the same time, love remains ever-present in Kennedy’s dreamworlds.

But no matter how dreamlike and abstract her words can be, Kennedy’s legacy is often characterized by darker, more violent images. Hilton Als opens this 2018 profile for The New Yorker by noting:

“Blood” is one word that comes up. Blood as poison, blood as might. Other words—“help” and “cry”—are among the verbs most likely to be spoken by the eighty-six-year-old playwright Adrienne Kennedy’s characters. These bitter, lovesick words—sharp bleats of distress—rise and cling to the curtains and the walls in the ghastly showrooms of her characters’ troubled, hope-filled, and hopeless minds.

Scott Brown makes a similar point in this 2022 New York Times Style Magazine piece:

Since her theatrical debut with Funnyhouse of a Negro Off Broadway in 1964, at 32, Kennedy has addressed the heart- and head sickness of racism, the confusion of sex and gender and the illusion of the self with incantatory paradoxes, visceral symbols, sidelong pop-culture references and violent contradictions.

Kennedy’s work evokes the abstract violence of nightmares and dying dreams, and propels forward discussions of racism, sexism, and colorism. Her art is enchanting, exhausting, and overflowing with memoir. Yet, despite the decapitated heads in her Obie-winning Funnyhouse of a Negro and the bleeding set pieces in Sun, her play-in-poetry dedicated to Malcolm X, the love sowed into each of her works strikes me as the most fundamental part of comprehending her as a writer. Indeed the word “love” and its many iterations (loved, beloved, lovely, etc.) appear more often in Adrienne Kennedy: Collected Plays & Other Writings than “blood” or “death” and their many forms.

The further into Kennedy’s oeuvre one reads, the more love can be found. Even the earliest unpublished piece included in the LOA volume, The Tiger and the Tomboy, centers around the juvenile love between Sandra and Ty that is ushered into reality with the help of their imagined double-selves, Tyrone and Shari.

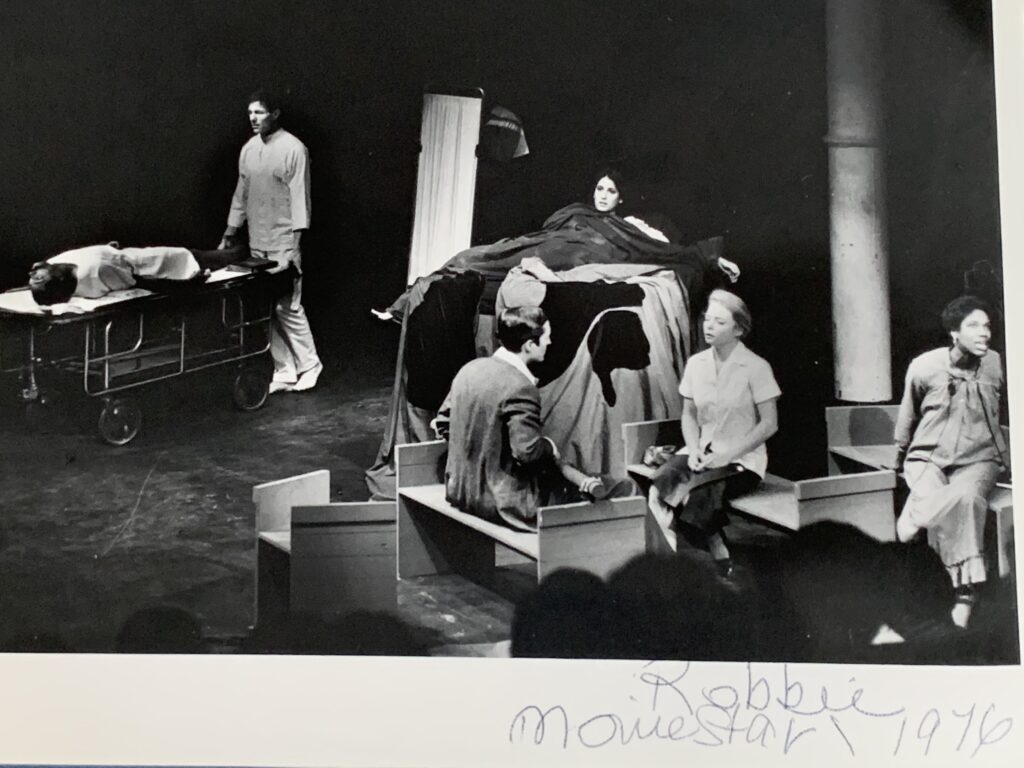

Still from 1976 New York Shakespeare Festival production of Kennedy’s A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White, directed by Joseph Chaikin (photo: George E. Joseph)

In Kennedy’s first published pieces, Black women protagonists grapple with mixed-racial paternal love. In The Owl Answers, “she who is Clara Passmore who is the Virgin Mary who is the Bastard who is the Owl” is a biracial Black woman endlessly trying to reach her white father. When talking to “Bastard’s Black Mother who is the Reverend’s Wife who is Anne Boleyn,” the main character Clara asks of her, “Anne, Anne Boleyn. . . Anne, you know so much of love, won’t you help me? They took my father away and will not let me see him.”

In Funnyhouse of a Negro, the character Sarah communicates externally with her fractured consciousness via “one of herselves”: Negro-Sarah, Duchess of Hapsburg, Queen Victoria Regina, Jesus, and the assassinated Congolese political leader Patrice Lumumba. The selves describe her father taking his own journey to reach her. Queen Victoria, the first in the play to speak, says in response to a knocking, “It is my father. He is arriving again for the night. . . . He comes through the jungle to find me. He never tires of his journey.”

Close to the end of the play, all of Sarah’s selves recite several times:

I am bound to him, unless, of course, he should die.

But he is dead.

And he keeps returning. Then he is not dead.

Then he is not dead.

Yet, he is dead, but dead he comes knocking at my door.

Sarah’s landlady, a “tall, thin, white woman” who “laughs like a mad character in a funnyhouse throughout her speech,” says of Sarah’s father, “he wrote to her saying he loved her and asked her forgiveness.” Even in death, Sarah’s father’s endless journey to reach her is full of love.

In both plays, the fractured identities of the central characters exemplify how the violence and absurdity of racism harm the mind and body. At the same time, love remains ever-present in Kennedy’s dreamworlds. Sarah’s father—even from the dead, even in the demented mirror house representing Sarah’s collapsing consciousness—returns every night for love. Clara embarks on her own journey for love, trying to reconnect with her father despite his and others’ disgust.

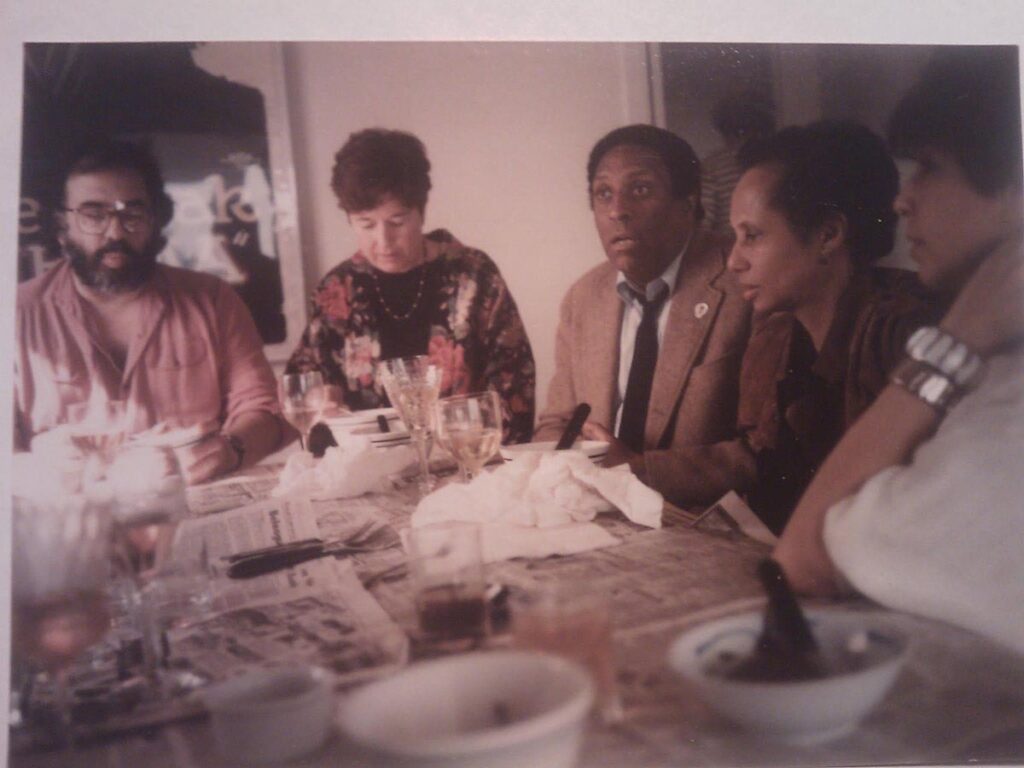

Kennedy lunching with Francis Ford Coppola (far left) in the 1980s (Criterion / Adrienne Kennedy)

The trend continues through Kennedy’s later work as well. In Black Children’s Day, published for the first time in the LOA volume, Black children rehearse for a play about the violent history of their New England town, reenacting gruesome scenes depicting a battle between Indigenous Americans and colonists, a bloody election day between white and Black Americans, a “lost” 1840 slave ship, and the sailing of the Free African Society to Liberia. The brutality of the past is met with the horrors of the present as a radio pronounces the threat of Nazi Germany, World War II looming. Amid this violence, though, Kennedy extends a thread of love: “Roy and Constance who have been in love since the second grade. Today is their wedding day.”

He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box, published in 2020, follows Kay, a biracial young woman, and Chris, a young white man, after leaving their hometown in Georgia. The two correspond via letters during World War II while Kay attends college and Chris pursues acting in New York. The couple hope to marry one day and leave their pasts behind. Kay’s white father is rumored to have murdered Kay’s young Black mother, keeping her dead heart in a green box. Chris, meanwhile, grapples with his own father, a prominent white man responsible for setting the Jim Crow boundaries of their town.

As the play progresses, Kennedy depicts the internal and external forces inherent to Kay and Chris’s relationship: the racism and sexism of their parents’ relationships hold up a mocking mirror to their own. Eventually, Chris finds someone who will marry the couple in Harlem, inspiring hope that “we could run away and live in Paris after the war.”

In Almost Eighty, another scrapbook-like work, Kennedy confesses, “I wondered if I could find reasons to live.” In the piece, she works out how to find resilience to continue living for herself and her loved ones, concluding, “I thought: I could still show devotion and courage. I could. I can.”

One could argue that Kennedy’s writing has always exhibited immense courage and devotion. Despite the unthinkable violence of racism and sexism confronted by her work, it takes bravery to consistently allow love to be present. Even though Roy and Constance from Black Children’s Day and Kay and Chris from He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box are not allowed to live and love each other—the cruelty of the world takes that possibility away—Kennedy lets the love exist anyway. Even in dehumanizing times, she seems to say, love persists—whether disgusted with itself, bent, broken, hidden, disgraced, pursued, or absent altogether. Love that ends in death. Resilient love. Bold love. Brave or pitiful love.

Still from 1976 New York Shakespeare Festival production of Kennedy’s A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White, directed by Joseph Chaikin (photo: George E. Joseph)

***

I will always be thankful Kennedy chose to share her work with Library of America. Her ability to depict the harsh realities of racism, sexism, and colorism, and to further conversations about the contradictory comprehensions of living in America while being African American, demonstrate unequivocally her immense courage. The way she holds the world around her with such reverence and devotion, sharing her “wonders” throughout her work, is a gift to us all.

It was an honor to work on this volume and contribute to the ongoing confirmation of Adrienne Kennedy as a vital force in American theater and literature. She knows so much of love. Let her work speak to you and you will learn much about love, too.

Ariana Pettis studied English and drama at the University of Virginia and is a former Library of America Diverse Voices Editorial Fellow. She currently lives in Virginia.