Three incarnations of Show Boat: original sheet music cover (Public Domain), scene from the 1928 Broadway production (Public Domain), and still from Show/Boat: A River, 2025 (photo: Greg Kessler)

We’re pleased to present this essay on the recent spate of Broadway musical revivals by Laurence Maslon, editor of LOA’s two-volume American Musicals edition and Kaufman & Co.: Broadway Comedies.

by Laurence Maslon

The American musical is the Swiss Army knife of popular culture. It can be deployed in venues as small as high school auditoriums and summer camps or as large as Broadway theaters and opera houses. It can be experienced as a multimillion-dollar movie or as a live television broadcast. It can be heard in pop renditions, jazz renditions, cabaret performances, on Spotify playlists—even on those flat black round things they used to call “records.”

What the musical could not be, according to its original creators—songwriters, book writers, sometimes even directors or choreographers—was tampered with. For decades, the original creators of our classic musicals and, subsequently, their estates, held fast to the authorial intent of their immensely lucrative pieces of intellectual property (unless, of course, any changes were made by the collaborators themselves).

One could argue that the leading collaborator in this evolution—if indeed it is an evolution—is the zeitgeist itself; the twenty-first century seems not only to accept but perhaps to demand the increased permissiveness and sexual frankness of these most recent revivals.

At the stroke of midnight on January 1, 2025, all of this changed. Show Boat (1927)—with a score by Jerome Kern, book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, and based on Edna Ferber’s novel—is universally considered among scholars and mavens to be the first great narrative musical, and a groundbreaking (and popular) addition to the Broadway canon. It would also become the first important and enduring musical to enter the public domain.

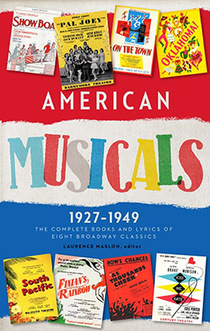

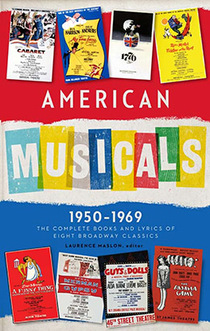

Copyright is but one reason for the changes in three recent reboots of beloved American musicals. In the past few months, Show Boat, Gypsy, and Cabaret (all of which appear in the two-volume LOA anthology American Musicals 1927–1969) have been revived in New York, each one pushing the boundaries of authorial intent and each one asking audiences to experience classics from new perspectives.

Since its original 1966 Broadway production, Cabaret (score by John Kander and Fred Ebb, book by Joe Masteroff) has been revived four times, each revival influenced by the successful 1972 film version directed by Bob Fosse, who had nothing to do with the original production. Fosse and his cinematic collaborators became fascinated with the Weimar atmosphere of the musical. Inspired by the source material by Christopher Isherwood, they expanded the sexual dimension of the original Broadway book on one hand while at the same time centering more of the action inside the seedy Berlin nightclub known as the Kit Kat Klub. The huge success of the film version dictated what audiences wanted when they came to the theater, and subsequent stage revivals incorporated much of the film’s material and perspective, including several songs written expressly for the movie. (Much of this material can be found in the appendix to the American Musicals volume.)

Two productions of Cabaret: Anne Beate Odland as Sally Bowles in 1975 (CC BY-SA 3.0) and Liza Minnelli and Joel Grey in the 1972 film version directed by Bob Fosse (Britannica)

The current revival at the August Wilson Theater takes its cue from the 1998 revival (itself revived in 2014), which places the Kit Kat Klub front and center, practically as the main character (in fact, this revival is technically called Cabaret at the Kit Kat Club). The louche goings-on at the site-specific cabaret setting put more of a spotlight on the diegetic songs performed by the Emcee, the singer Sally Bowles, and their crew, and several of the more benign, book-oriented character songs of the 1966 original have been cut.

2025 production of Cabaret at the Kit Kat Club (Marc Brenner)

One could argue that the leading collaborator in this evolution—if indeed it is an evolution—is the zeitgeist itself; the twenty-first century seems not only to accept but perhaps to demand the increased permissiveness and sexual frankness of these most recent revivals. In any event, any textual changes were approved by representatives of the original creative team, including John Kander, who is blessedly still with us at the age of 97.

Gypsy, with a book by Arthur Laurents and a score by Jule Styne and Stephen Sondheim, is perhaps the hardiest of all the book musicals of the twentieth century, having been revived five times since its 1959 debut. It’s not hard to understand Gypsy’s popularity with audiences—it’s got a very solid book and a terrific score—but its ace in the hole, as it were, is that it offers one of the great female leading parts in the American canon, musical or otherwise: Momma Rose, the domineering dynamo at the show’s center. Leading ladies of a certain age seem obligated to tackle its challenges, and this past November, Audra McDonald, the greatest singing actress of her generation, felt it was her turn to climb this particular mountain.

Audra McDonald in the 2025 production of Gypsy (photo: Julieta Cervantes)

More than most of the classic musicals, Gypsy has been policed by its original creators. Arthur Laurents was particularly protective of the material and directed several of the Broadway revivals, grabbing the torch from Jerome Robbins, who directed and choreographed the original production. In fact, Robbins’s brilliant choreography was considered so essential to Gypsy’s narrative that it felt part of the original authorial intent and has often been reproduced in revivals, even after Robbins’s death in 1998.

The current revival of Gypsy (which deploys new choreography by Camile A. Brown) is a collaboration between McDonald and her frequent collaborator George C. Wolfe, one of the finest directors working in the theater and film today. Wolfe, like McDonald, is Black, and this is the first time on Broadway that Gypsy had been given a Black lead and the opportunity to reflect the Black experience in the entertainment world of the early twentieth century. Before this revival opened, there was a lot of chatter as to whether the original text was flexible enough to represent the Black experience in vaudeville and burlesque (the show’s most prominent venues) and if any of the text would be changed—or could be changed—to accommodate McDonald. Would this Momma Rose be a Black character or would McDonald’s rendition ask audiences to ignore her racial identity? As columnist John McWhorter pointed out in The New York Times, the entire theatrical and musical vocabulary of Black vaudeville (known in its day as the Chitlin Circuit) was so different from white vaudeville that any shift would necessitate an entirely new score—and given the frequently inflexible demands of the Laurents’s and Robbins’s estates, major textual changes would never happen.

It’s satisfying to report that Wolfe and McDonald have managed to create a counter-narrative without appreciably changing the text or the score. McDonald plays Rose as a Black woman with two Black daughters, the eldest with a much lighter skin tone. This allows Wolfe to derive a subtext about colorism from the original book. McDonald’s Rose pushes the lighter-skinned daughter as a potential star; as she manages their limited ascent up the ladder of vaudeville, Rose replaces Black chorus members with white ones. It’s clear that in Wolfe’s vision of Laurents’s trajectory of twentieth-century entertainment, white performers will always be more accepted than performers of color—until the show’s climax, where the darker-skinned daughter, Louise, steps in and achieves showbiz fame by accessing some of the moves and characteristics of Josephine Baker, arguably the most popular Black stage presence of the 1920s and ’30s. Wolfe and McDonald pay respect to the original authorial intent of the material, but use their own vivid imaginations and vibrant hues to portray a viable parallel narrative.

Zachary Daniel Jones, Tony d’Alelio, Jordan Tyson, Kevin Csolak, and Brendan Sheehan in the 2025 production of Gypsy (photo: Julieta Cervantes)

The situation with Show Boat is another kettle of fish entirely. Back when it opened, five days before the end of 1927, Show Boat, with its epic narrative, racial complications, and complex themes, was the most advanced and adventurous musical of its day by a nautical mile.

When David Herskovits, artistic director of the off-off-Broadway company Target Margin, decided to tackle Show Boat for a standalone production in January 2025 at New York University’s Skirball Center, he would be the first director to have complete and unfettered control over the elements that comprise Show Boat—at least those materials written by Kern and Hammerstein up to the show’s opening on December 26, 1927. (Both creators made many important additions and deletions in subsequent films and revivals through 1946; these are also found in the American Musicals collection.)

Given his small ensemble, Herskovits was obliged to reduce the cast size of the mammoth original text and he could make any other emendations he chose. Indeed, lines were cut or reassigned, and even in one case an important role—originally that of the white matriarchal figure Parthy—was assigned to a Black actress and a white actress simultaneously. The more complex changes involved the score itself. After almost one hundred years of Show Boat, even in its various film adaptations and stage revivals, we are accustomed to a certain kind of consistency in the way the songs fit into the narrative. However, now that all the material is in the public domain, one could do frankly whatever one likes with the score, no matter how it had been performed in the past or what the audience’s expectations might be. In the future, for example, one could produce The Sound of Music and add songs by Mozart and Palestrina to be sung by the Von Trapp Family Singers, as indeed was the case in real life (and was the original proposal from the musical’s producer until Rodgers and Hammerstein got involved). One could produce the 1975 Kander and Ebb musical Chicago, set in 1927, and add, say, “The Birth of the Blues,” a very popular jazz number by another team from 1926. The shift in the musical vocabulary for these shows would be unprecedented and no doubt disorienting for those familiar with the originals.

Alvin Crawford, J Molière, Tẹmídayọ Amay, Suzanne Darrell, and Stephanie Weeks in 2025 Target Margin production of Show/Boat: A River (photo: Greg Kessler)

Aside from new orchestrations and musical arrangements, the Target Margin version of Show Boat interpolated very little from sources outside Kern and Hammerstein. In the 1927 version, a scene set at the 1893 Columbian Exposition featured a dreadfully inappropriate number called “In Dahomey,” sung by a group of Black performers pretending to be Zulus. It’s usually cut, but at Skirball, a brand-new number for the Black cast members by music director Dionne McClain-Freeney and sung in isiZulu was added. In the 1927 text, Kern and Hammerstein took the bold initiative of interpolating one of the most popular songs from 1890s, “After The Ball” (written by Charles K. Harris), into a sequence set in 1904; they were happy enough to access the flavor of the period without the necessity of writing their own proprietary material. In the Skirball revival, a new song by McClain-Freeney was substituted; it was neither resonant of an earlier time nor particularly inspired. The intriguing possibility of, say, adding a Gershwin song from 1926 to the score of a show with a final scene set in 1927 was not exploited. But that’s probably just a matter of time.

As the copyright-protected edifices of the American musical’s revered properties begin to crumble, the intricate constructs of the genre, the authorial intentions of its many precocious creators, and its immense commercial possibilities are faced with extraordinary challenges. Luckily—if that’s the word for it—Show Boat (and the Gershwin/Kaufman/Ryskind political spoof Of Thee I Sing from 1931) is the only real great classic prior to 1943 and the premiere of Oklahoma!, which ushered in Broadway’s golden age. Unless there is an unanticipated change in the current copyright laws, we will have to wait sixteen years to observe in what way the classic American musical canon will continue to keep rolling along.

Caricature drawing of Show Boat cast from a 1928 production (Public Domain)

Laurence Maslon is an arts professor at New York University. He is the editor of LOA’s American Musicals as well as the editor of Kaufman & Co.: Broadway Comedies, which features Of Thee I Sing as well as George S. Kaufman’s other important comedies.