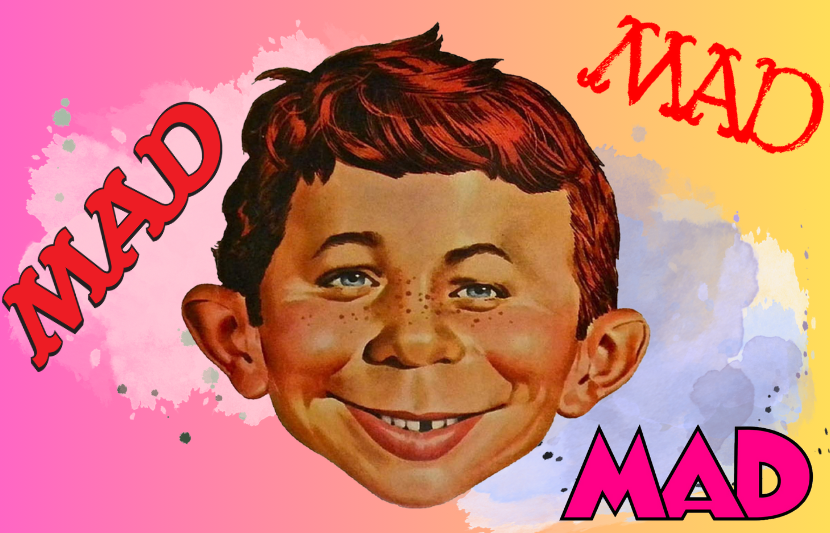

Alfred E. Neuman and assorted MAD magazine logos

Some of the most incisive and unrestrained observations about twentieth-century American life originated not from novels, poetry, or journalism, but from the lurid, absurd, and gleefully overflowing panels of MAD magazine. Fittingly, this achievement was almost entirely accidental.

“The out-of-control things that happened in the pages of early MAD were of the sort that occur when people are not erecting monuments,” writes Geoffrey O’Brien in his essay for the just-published The MAD Files: Writers and Cartoonists on the Magazine that Warped America’s Brain! MAD’s creator, Harvey Kurtzman, drove the point home: “When you’re desperate to fill space, you think of outrageous things.” If necessity is the mother of invention, then MAD’s golden era—the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, or whenever a dedicated reader happened to be twelve years old—represents an anarchic highpoint of comic creativity, sometimes crass, often sophomoric, always committed to a vision of transcendent lunacy.

In this interview with Library of America, volume editor David Mikics discusses his longstanding admiration of this explosive periodical, whose omnidirectional ridicule left no sacred cows unscathed. Pop culture, religion, suburbia, hippies, presidents, and even its own audience became fodder for eye-popping spoofs, illustrated by genius artists who drew equal inspiration from Breughel and Batman. Read on for Mikics’s reflections on MAD’s high-school-cafeteria origins, its deep roots in Jewish humor, and what its merciless hilarity can teach us about the real world.

LOA: What was the cultural moment MAD emerged from in the 1950s, an era many associate with straitlaced conformity very much at odds with the magazine’s antic and anarchic vision?

David Mikics: The clichés about the ’50s tend to be correct. If you lived in the suburbs, everything had to be rigid, orderly, under control. Mary Fleener, in her essay for the anthology, talks about the clothes people wore, which were virtually imprisoning them: Dad would have these shiny black shoes, his socks were held up by garters, he wore a hat and a constricting necktie. Mom would have a girdle and a bullet bra. R. Crumb, for example, who suffered deeply in his childhood from a very strict Catholic parental regime, would make fun of this wonderfully: the uptight dad of the 1950s, grinding his teeth and oozing conformity.

MAD was the antithesis of all that; it was the anti-conformist Bible. It was iconoclastic, it poked fun at everything. What Geoffrey O’Brien says in his essay is very much to the point here, that the culture of the time took itself very, very seriously. Nowadays, it doesn’t—advertisements make fun of themselves, for example—but in those years, there was a certain solemnity, even to ads.

Then on the other hand, there were glimmers of something new on the horizon. You had The Ernie Kovacs Show in the early ’50s, you had Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows. These were real goofball comedies, things that upset the applecart and parodied mainstream culture. But for the most part, the comedians you were going to be seeing at that time were people like Jack Benny and Bob Hope, recycling the same routines, the same jokes, year after year.

They turn characters like Superman and Batman into schlemiels and schlimazels. Our superheroes become the unwitting perpetrators of outrageous errors and goofs that everybody else has to suffer through.

The ’50s was a feast of material for MAD, and it also illustrates the importance of parody—and self-parody—for the magazine. Parody was not really central to American humor before MAD, and that was one of the things that made it revolutionary.

LOA: The rigid, rule-bound world MAD ridiculed is very different than the cultural atmosphere we inhabit today, which is much more ironic and postmodern in its sensibilities. Would readers of classic MAD have found it shocking? And by the same token, have twenty-first-century readers lost the ability to register how boldly irreverent it was?

DM: Strange as it may seem, MAD came out of EC Comics, which published horror and science fiction and other genre strips. Bill Gaines had inherited that business from his father, Max, and he started something new in 1952, a parody comic book that after a few years became MAD magazine.

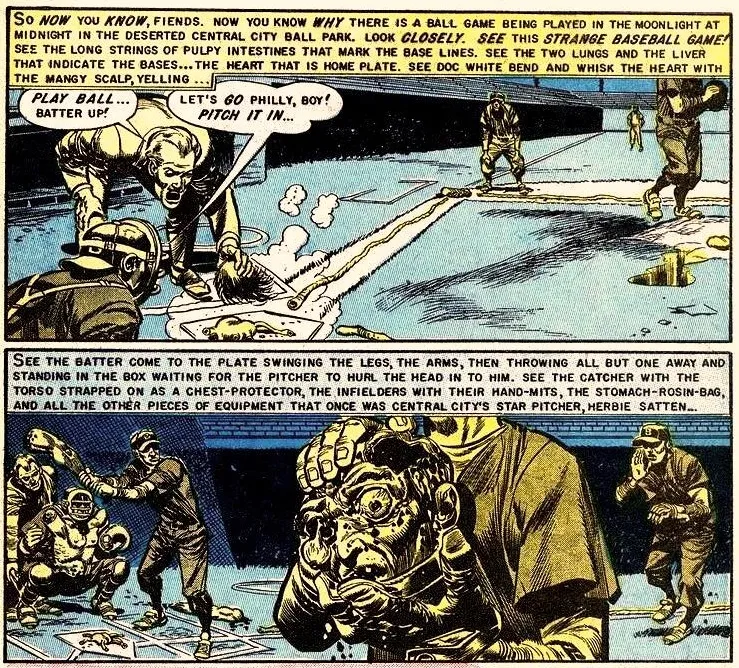

The reason I mention this is that if you look at the EC Comics of the early ’50s, the horror comics were quite gory; they would be shocking to us today! A doctor, Fredric Wertham, testified in the Senate about the danger that comic books presented to the juvenile mind, and one of the examples he pointed to was a panel in which you have a guy’s intestines lining the bases of a baseball diamond and it’s as horrifying as any slasher film.

Panel from “Foul Play,” from The Haunt of Fear, Vol. 1, No. 19 (EC Comics, 1953)

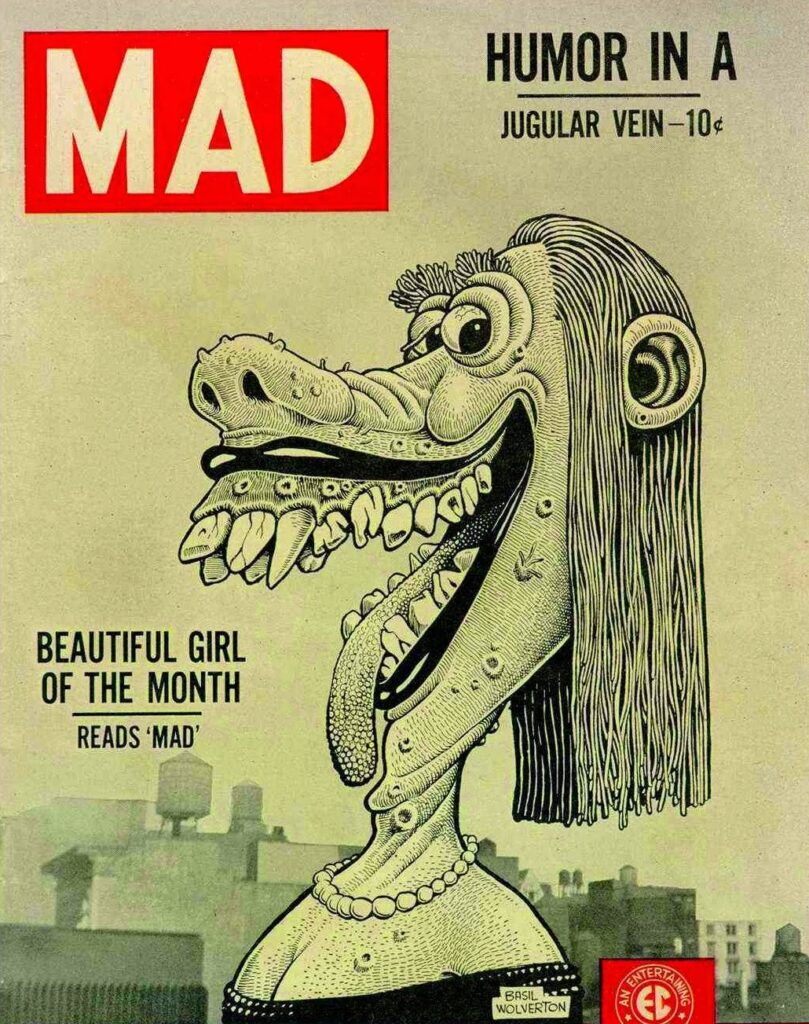

But what would have shocked people about MAD? Well, there’s one image that several of the anthology’s contributors mention, which is Basil Wolverton’s cover art for “Beautiful Girl of the Month.” She has a sort of Mona Lisa smile, but it’s actually a hideous grin. She’s covered with warts and sores, she has spaghetti-strand hair. Art Spiegelman and Mary Fleener talk about when they first saw this cover and they just went, “Whoa!” They’d never seen anything like it before. This kind of sicko or bizarre humor was something I think would have merited the word “shock.”

“Beautiful Girl of the Month” cover by Basil Wolverton (MAD, No. 11, 1954)

LOA: Who was MAD’s audience? On the one hand, it seems pitched primarily to adolescent boys. But in retrospect, you see MAD having pretty wide appeal across ages and genders. How can we think about this varied mix of viewpoints that constitute the memory of peak MAD?

DM: To wax autobiographical, I discovered MAD at around age eleven or so, in the early ’70s, at the height of its popularity. Its best-selling cover ever was “The Poop-seidon Adventure,” parodying the famous disaster flick. On the cover you see a lifesaver floating in the sea with Alfred E. Neuman’s legs sticking out—he’s put it on the wrong way. I had seen The Poseidon Adventure, so I appreciated that parody, but they also had parodies of movies I had not seen, and in some cases was not allowed to see.

As many of the anthology’s contributors say, they learned a lot from MAD; one talks about how he would, in the early 1960s, astonish his parents by babbling at the dinner table about Jimmy Hoffa and Fidel Castro. I learned about swingers and beatniks and hippies and LSD. I remember one of the Peanuts parodies in which Charlie Brown and crew are these very scruffy Berkeley hippie types and you see Linus sort of slumped over studying his belly button: this is his acid trip and he’s bummed out because he sees all these Charlie Brown faces making up the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, which was very popular in those days, the ultimate sort of straightlaced, wholesome choir.

LOA: For something often thought of as deeply sophomoric, MAD also posited a way for children to learn about the complexity of the world. The quote that comes to mind from the anthology is Geoffrey O’Brien on MAD’s omnivorousness, how the writers and artists felt compelled to fill space with everything and anything. The magazine had an almost Talmudic nature, with the writing in the margins and the proliferation of commentary upon commentary.

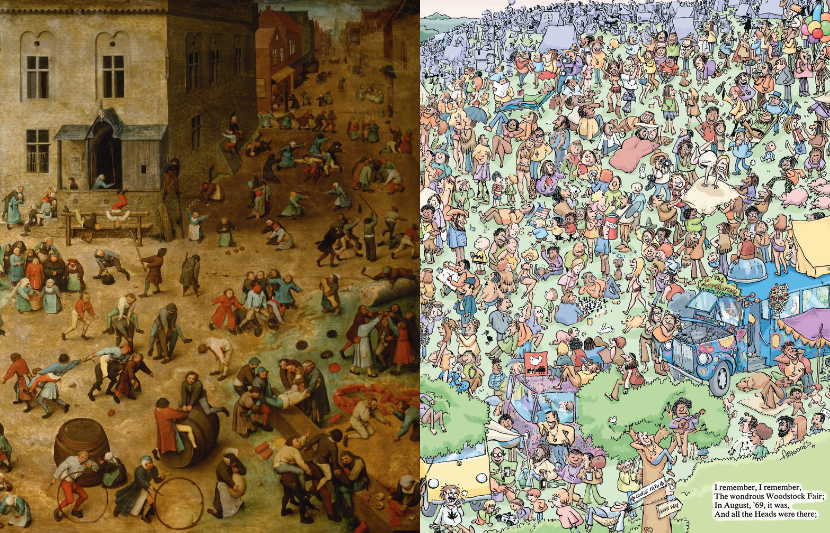

DM: One of our contributors, Liel Leibovitz, actually compares a page of MAD to a page of the Talmud, because you have in the margins these blocks of text commenting on the central piece, compelling the reader to flip back and forth between them. MAD did that most notably with Sergio Aragonés’s cartoons, which are these little skittering, stray details in the corners of the pages. And in MAD’s famous movie parodies, there’s always something going on in the corner of the frame. Will Elder was especially given to festooning his panels with all sorts of interesting jabberwocky and tiny little reflections here and there. You can also see this in a parody of Woodstock clearly based on Breughel’s great canvas Children’s Games, where you have all these hippies cavorting in antic ways all over the panel.

Details from Children’s Games by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and MAD parody of Woodstock, illustrated by Sergio Aragonés (MAD, No. 134, April 1970)

But MAD also had certain obsessions. One that struck me very deeply when I was a kid was its portrayal of the cigarette industry—you have all these MAD parodies where the pack of cigarettes is a coffin. That was a real hobbyhorse for them.

It was frequently hard to tell what side MAD was on in cultural disputes, and that was one of the great things about it. They made fun of both the hippies and the “moral majority,” long before the phrase “moral majority” was used. One movie parody that particularly makes that point is Nick Meglin’s sublime take-off on My Fair Lady, “My Fair Ad-Man.” It’s penciled by Mort Drucker and written by Meglin (who many years later would become MAD’s editor), and it’s about a beatnik who is turned into a Madison Avenue executive. The main target is Madison Avenue, always spelled with “MAD” in capital letters, but the beatnik also comes in for his share of whacks. They directed their parody at all sides.

LOA: How can we think of MAD’s place in the lineage of Jewish American humor? Not to say that MAD is a strictly Jewish cultural artifact, but it’s undoubtedly part of the story of how Jewish culture influenced American culture more widely. Could you talk about this dimension of the magazine and how this strain of humor evolved through MAD’s history?

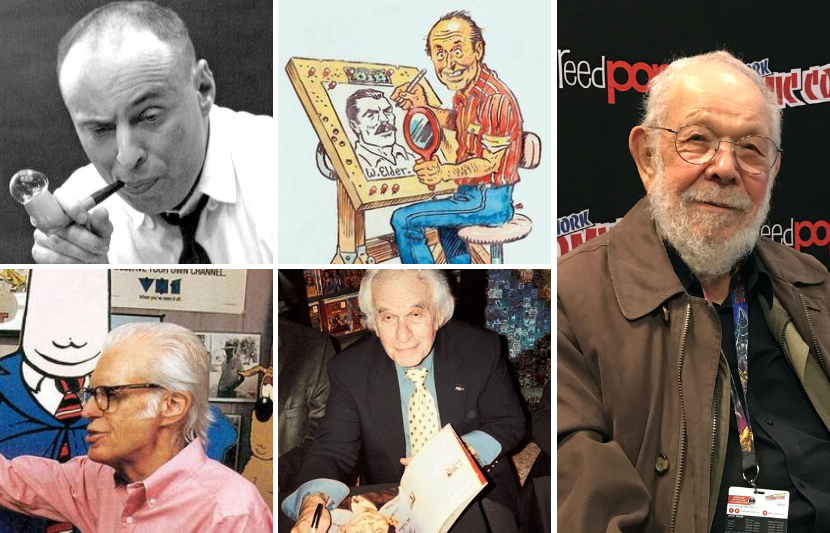

DM: That’s a fascinating subject. MAD was seen as Jewish humor by the original crew, “the Usual Gang of Idiots,” as they called themselves. When Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman were hanging out in their New York high school cafeteria, they would do these goofy parodies of movie scenes. Then they found that the other Jewish writers and artists at MAD had done the same thing in their high school cafeterias. Their ambition, as one writer in the anthology says, was to turn the whole nation into that high school cafeteria.

MAD’s “Usual Gang of Idiots.” Clockwise from top left: Harvey Kurtzman (The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics, Abrams Books, 2009), Will Elder (self-portrait, Wikimedia Commons), Al Jaffee (Luigi Novi / CC BY 4.0), Mort Drucker (Gustavo Morales / CC BY-SA 3.0), and Don Martin (Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, defining Jewish humor is a bit of a mug’s game, but one thing you could say is that it’s self-deprecating: it makes the point that we’re all fools. And often in Jewish jokes, you’ll have a sort of holy fool or idiot as the star of the show.

I have to pause here and tell my favorite joke: there’s a Frenchman, a German, and a Jew stranded on a desert island and a genie comes along and says, “You’re each granted one wish. What is it?” The German guy says, “I want to be back in Berlin with my wife.” He disappears and the French guy says, “I want to see my mistress in Paris.” And so he goes away too. Then the genie asks the Jewish guy, “OK, so what’s your one wish?” And the Jewish guy responds, “Well, I kind of miss those guys. I wish they were back here.”

It’s a joke that’s very clearly about the Jewish predicament of being stuck with these Europeans who are persecuting you, and yet, for some strange reason, you’ve decided to stay there with them. And it’s also about somebody who can’t think of anything sufficiently liberating or imaginative to wish for. There are all kinds of dimensions to it. But in these terms, the Jewish hero is a kind of loser.

Consequently, in MAD, they turn characters like Superman and Batman into schlemiels and schlimazels. “Schlimazel” means literally someone who’s the victim of bad luck, and “schlemiel” is someone who can’t do anything right. So our superheroes become the unwitting perpetrators of outrageous errors and goofs that everybody else has to suffer through.

Al Jaffe is a unique case, in that he was born in the United States, but then his mother took him back to the shtetl in Lithuania when he was a kid. In a tragic turn, he ultimately came back to the U.S. to be with his father in 1933 and she stayed behind in Lithuania.

Jaffe said that in the shtetl everything was so repressed. You had all these authority figures—the rabbi, chiefly—and you made fun of them. This explains the genesis of one of the most famous invented MAD words, “potrzebie,” which to Jaffe is actually “putz rebbe,” something people would say in Lithuania to ridicule the rabbi.

And then, of course, “furshlugginer” is a made-up Yiddish word, but they also used familiar Yiddish words like “gonif,” meaning “thief,” and there are references to Manischewitz and some other familiar Jewish artifacts.

MAD is certainly one of the major vehicles for introducing Jewish humor and vocabulary to American culture. But they also, of course, satirized all religions: everything was meat for the grinder.

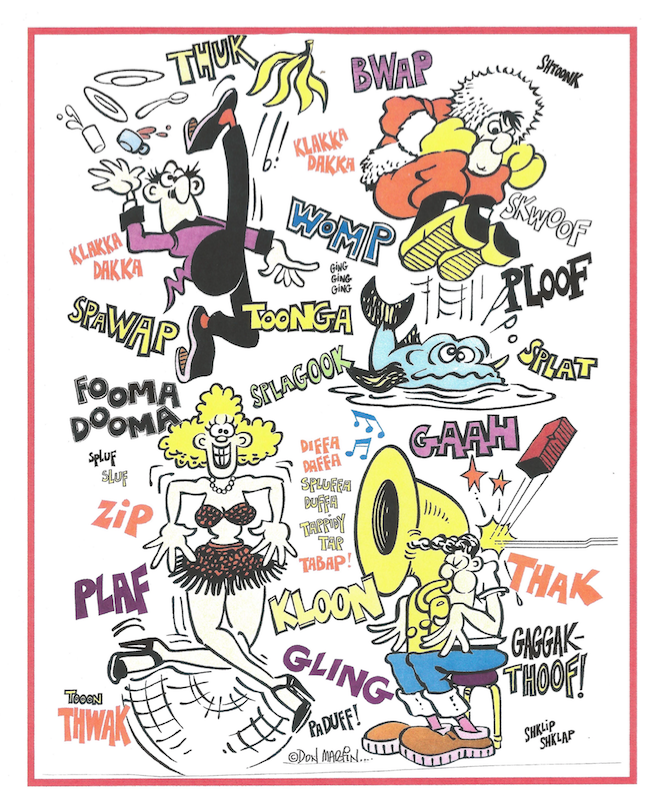

Flock of Sounds woodprint by Don Martin (Fine Art America)

LOA: What do you consider the high points of MAD? What eras might new readers want to focus on, and when did MAD’s influence start to wane?

DM: I’d say the peak is 1950s, ’60s, ’70s. Of course, if you want to be a snob, you could say the real peak was under Harvey Kurtzman, from ’52 to ’54. Under Kurtzman, the movie parodies looked utterly sublime. Wally Wood and Jack Davis and Will Elder were doing astounding things that comic books had never done before in terms of artistic vision.

By comparison, the later Mort Drucker parodies are much more humdrum—he was a genius artist, the way he was able to take these familiar actors and parody them—but it’s more subdued. There aren’t these explosions of color. In those early movie parodies, the point of the jokes often gets drowned in the explosion of artistic brilliance, which is not the case later on.

But as one of our contributors points out, the golden age for MAD is whenever you were twelve years old. I think it was going strong well into the ’80s, but in 2018 the original version of the magazine folded. Still, if you go into a Barnes & Noble, you will find anthologies drawn from these recycled issues of MAD; they’re being kept perpetually in print, so kids can still experience the golden ages.

LOA: The artistic talent at MAD is in some ways inseparable from its comedic content. But at the same time, a younger reader could pick up an old issue, and even if the references are unfamiliar to them, they can still engage with it on the level of artistry and craft.

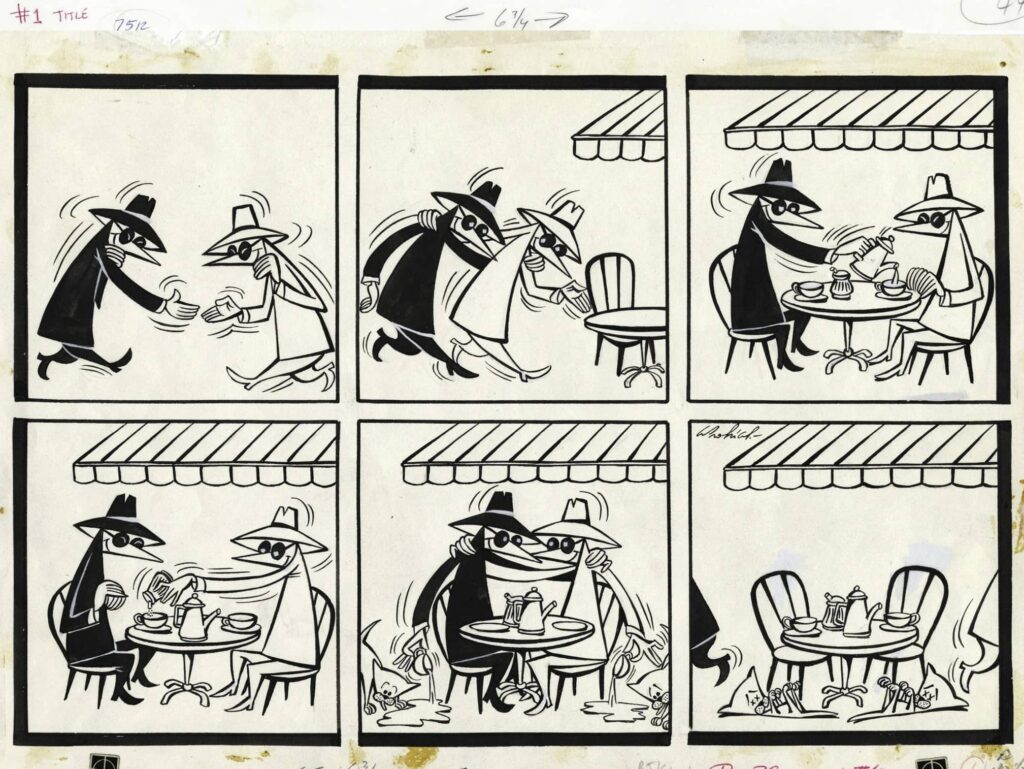

DM: From the early years, you have great artists like Elder and Wood and Davis and Kurtzman, but also Marie Severin, who was a brilliant colorist and one of the few women artists who worked for the magazine. These artists had such distinctive, signature styles, like Prohías with “Spy vs. Spy.” There’s nothing else like it. I say in the book that it’s more like the diagram of a joke than the joke itself. It’s the drawing as a puzzle.

“Spy vs. Spy” strip by Antonio Prohías (Heritage Auctions)

And then you had the skittering doodles by Aragonés. You have Don Martin, who at first glance might seem to be casual in his lines but who is actually highly precise. His goofiness, those clown shoes and dangling noses and floppy hands, are wonderfully suited to his brand of self-consciously foolish jokes. And then of course there are those words that he uses, like “blorp” and “stoopft”—there’s an entire online glossary of them.

It’s the collection of their styles that’s so special; you recognize each of them as utterly distinct. You needed all of them together.

Part of MAD’s artistic legacy is that you can admire it without “getting” the jokes, then go on to try and puzzle them out. You asked your friend or your parents, “What is humor in a jugular vein? What is a jugular vein?”

Readers can still do that now, even though the whole cultural atmosphere has changed. Advertisements may make fun of themselves now, but you still have the stiff pomposity of the straightlaced, respectable existence you’re supposed to lead. I love the way Roz Chast puts it in her cartoon, where she pictures a man saying something like, “Sports. Money, I am such a winner! Cars, golf.”

You have these ideals that are thrust upon us, perhaps now more than ever. We haven’t lost that, the idea of styling yourself according to some preprogrammed image. MAD said the hipsters and the hippies, they have to look a certain way. The respectable business executives, the suburban mom and dad, they have to look a certain way. Well, MAD readers have to look a certain way, too. Maybe a little more unusual, right? So they marketed a MAD straightjacket as garb for their fans.

MAD straitjacket (Heritage Auctions)

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick: American Filmmaker and Bellow’s People: How Saul Bellow Made Life into Art, and editor of The Annotated Emerson and Harold Bloom’s The American Canon: Literary Genius from Emerson to Pynchon. His writing has appeared in Tablet, The Nation, and The New York Times.