American assault troops in a landing craft during the Normandy invasion (U.S. Army / National Archives)

Eighty years ago, Allied forces landed in Normandy, punching a series of holes in the Third Reich’s Atlantic Wall and establishing a foothold in Western Europe. Part of the larger Operation Overlord, involving more than two million Allied personnel, U.S. forces followed up a pre-dawn drop of 13,000 paratroopers and 4,000 glider-borne infantry behind enemy lines with a 55,000-strong amphibious assault on Utah and Omaha beaches starting at 6:30 a.m. on June 6, 1944.

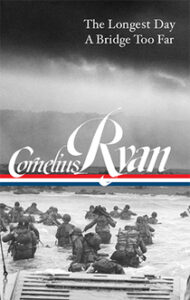

Their bravery, sacrifice, and ultimate triumph is often what comes to mind when we picture the events of D-Day—a shortening of “Day-Day,” military planning nomenclature for the date of any major action. The Longest Day, Cornelius Ryan’s harrowing and meticulous nonfiction narrative of the first 24 hours of the invasion, puts us on the frontlines of what its author described as “the bloody confusion of D-Day—the day the battle began that ended Hitler’s insane gamble to dominate the world.”

Drawing on his own experience as a war reporter, years of research, and more than a thousand questionnaires filled out by veterans (sample query: “In times of great crisis, people generally show great ingenuity or self-reliance; others do incredibly stupid things. Do you remember any examples of either?”), Ryan produced what may be the definitive popular account of the battle. (A 1962 film adaptation starring John Wayne, Henry Fonda, and Robert Mitchum is one of the highest-grossing black-and-white movies of all time.)

Original theatrical poster for The Longest Day (20th Century Fox, 1962)

Ryan places the moment U.S. troops make landfall in a longer lineage of American military heroism:

They came ashore on Omaha Beach, the slogging, unglamorous men that no one envied. No battle ensigns flew for them, no horns or bugles sounded. But they had history on their side. They came from regiments that had bivouacked at places like Valley Forge, Stoney Creek, Antietam, Gettysburg, that had fought in the Argonne. They had crossed the beaches of North Africa, Sicily, and Salerno. Now they had one more beach to cross. They would call this one “Bloody Omaha.”

American assault troops move onto Utah Beach (Public Domain)

But the weight of history was not the only thing sustaining the Allied attack. Behind the soldiers, in a chain of ships, aircraft, and personnel extending across the English Channel, lay one of the greatest mobilizations of manpower and materiel ever organized.

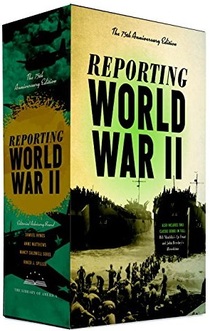

Few accounts conjure the astonishing scope of the operation more vividly than Pulitzer Prize–winning war correspondent Ernie Pyle’s reporting from the Normandy beachhead on D-Day Plus Two (i.e., June 8), included in LOA’s Reporting World War II anthology:

For a mile out from the beach there were scores of tanks and trucks and boats that you could no longer see, for they were at the bottom of the water—swamped by overloading, or hit by shells, or sunk by mines. . . . And yet we could afford it. . . . Men and equipment were flowing from England in such a gigantic stream that it made the waste on the beachhead seem like nothing at all, really nothing at all.

In March, we wrote about what B-17 navigator Elmer Bendiner called one’s “own tiny circle of war”—the tendency of those in battle to narrow their focus to the immediate matters of life and death before them, typically a far cry from the overarching designs of their commanders.

The celebrated war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, reporting from aboard a hospital ship in the Allied armada during D-Day, gives a stunning example of this phenomenon in a Collier’s article, also in Reporting World War II:

There were barrage balloons, always looking like comic toy elephants, bouncing in the high wind above the massed ships, and you could hear the invisible planes flying behind the gray ceiling of cloud. Troops were unloading from the big ships to heavy barges or to light craft, and on the shore, moving up brown roads that scarred the hillside, our tanks clanked slowly and steadily forward.

Then we stopped noticing the invasion, the ships, the ominous beach, because the first wounded had arrived.

American infantry on D-Day Plus One (Public Domain)

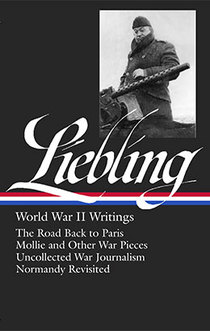

The New Yorker writer A. J. Liebling, stationed on a LCIL (Landing Craft Infantry, Large), notes a similar trick of perception in the heat of action:

On the morning of D-plus-one, Cope, the chief machinist’s mate, a tall, quiet chap from Philadelphia, told someone that from the order “Drop stern anchor” to the order “Take in on stern anchor,” which included all the time we had spent aground, exactly four minutes had elapsed. Most of us on deck would have put it at half an hour. During those four minutes, all the hundred and forty passengers we carried had run off the ramps into three feet of water, three members of our Coast Guard complement of thirty-three had been killed, and two others had rescued a wounded soldier clinging to the end of the starboard ramp, which had been almost shot away and which fell away completely a few seconds later.

LCIL during training for D-Day in England (Public Domain)

From a distance of eighty years, D-Day may now seem more like a glorified myth than an actual historical event. And yet in the vividness and diversity of the personal stories stemming from that epochal battle, June 6, 1944, becomes not just one pivotal day, but thousands of them: a sum of Allied energies, isolated and concerted. Less than a year later, on May 8, 1945, the German armed forces surrendered, bringing hostilities in Europe to a close.

“I am not actually writing about war,” Ryan once said of his books. “I use it only as a framework. I am writing about the human spirit in the midst of war—incredible courage, loyalty, hope, despair, and, all too often, ineptitude and bad management.” His is not an Olympian history told from above, but a story of individuals caught in the ferocious vortex of unfolding events.

Reading their words across the LOA series, we learn to honor those who fought on D-Day not just for what they accomplished on the beaches, fields, and villages of Normandy, but for the nightmarish reality they faced before the outcome was decided. Courage, after all, is not something granted after the fact, but what propels a person to acts of valor and duty in the first place, sometimes without them even knowing it. The ramp lowers into the water, the armada melts away, and we see suddenly through the eyes of a soldier as he steps forth into the terrifying uncertainty of history in the making.

Omaha Beach in 2011 (Anton Bielousov / CC BY-SA 3.0)