Carson McCullers: A Life (Knopf, 2024) by Mary V. Dearborn

Carson McCullers burned brightly in her all-too-brief career. A celebrated debut novelist by age twenty-three, she would go on to become an unlikely and iconoclastic hero of southern literature, chronicling the lives of outsiders and outcasts with rare sensitivity, heart, and empathy. But as her star rose, her battles with illness and alcoholism took their toll, ultimately claiming her life in 1967, when she was fifty years old.

On the strength of her small but spectacular bibliography—the arresting portrait of small-town southern life in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, the volatile fever dream of Reflections in a Golden Eye, the masterful storytelling of The Ballad of the Sad Café—McCullers has won legions of fans in the decades since her death, drawn both to her superlative prose and her singular persona.

In her new book, Carson McCullers: A Life (Knopf, 2024), biographer Mary V. Dearborn updates our vision of a woman who loved women, who married, divorced, and then remarried the same man, who was transgressive, queer, and committed to representing life on the margins throughout her fiction.

Below, Dearborn speaks with LOA about the author’s formative relationships with other artists and writers, her complex handling of race and sexuality, and how she fits (or doesn’t) into the grand American literary tradition of drunks.

Carson McCullers (Columbus State University)

LOA: How would you introduce Carson McCullers to new readers? What was her contribution to American literature?

Mary V. Dearborn: It’s a small body of work, because she died when she was fifty and her writing life was cut short by illness. She’s a southern writer, but I wouldn’t call her Southern Gothic; I’d call her Southern Weird. Altogether you’ve got about five or six novels, depending on how you define “novel,” and not much else. But there’s a lot in there, and she had a lot to say.

My introduction to her was through The Member of the Wedding, which is about a thirteen-year-old girl who doesn’t fit in anywhere and is the ultimate outsider. Frankie, the girl in the novel (with a boy’s name), wants to be part of anything—anything at all. We all think of ourselves as outsiders, even those of us who don’t seem to be. But for me, who actually was a thirteen-year-old girl when I read that book—and for various reasons objectively was an outsider—McCullers was very meaningful.

Who these characters are in their outsider-ness, or even freakishness—that was something she had great compassion for. And where you see this most clearly is in what I consider her best book, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, which she wrote when she was only twenty-three.

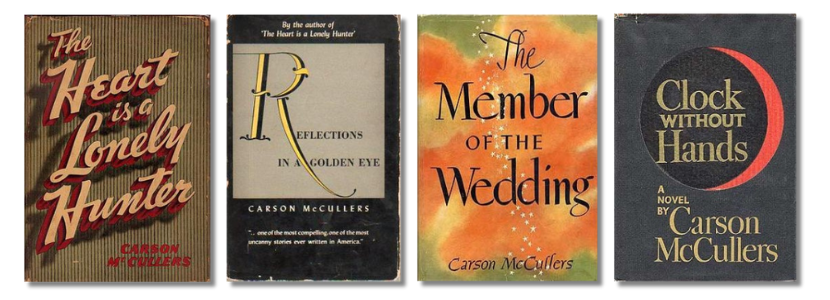

First-edition covers of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (Houghton Mifflin, 1940), Reflections in a Golden Eye (Houghton Mifflin, 1941), The Member of the Wedding (Houghton Mifflin, 1946), and Clock Without Hands (Houghton Mifflin, 1961)

LOA: You also talk, in the biography, about understanding McCullers as a queer writer—in fact, you say that this might be her defining trait as an artist. What do you mean by that?

MVD: I think it’s so central to her. I don’t necessarily mean her sexual preferences or experiences—there’s some question as to how much sexual experience McCullers even had. It’s more the sensibility that she brings to the experience of love and relationships in general that’s sort of awry.

If you give a more basic meaning of the word “queer” to it, I think that’s helpful in saying she’s not a lesbian and odd; it’s saying that there’s something fundamentally different about how she approaches things. She’s queer in the sense of transgressive. How she looks at relations between people and love can be fundamentally, I think, what I’d call queer.

McCullers did get married, to an Alabama native, Reeves McCullers, who was very much in love with her. In fact, I’d say that he was the one person on earth, except maybe McCullers’s mother, who loved her most. They divorced and then remarried, which has a degree of deliberateness to it that suggests they loved each other a lot. But fundamentally, she loved women, and Reeves himself had an affair with a man. It ended badly. Reeves killed himself. He was not a happy man and he was an alcoholic. Still, there was a kind of transgressive nature to the whole way they saw and felt for each other.

She didn’t want to be a concert pianist! She wanted to be Beethoven or nothing.

Researching the biography, I was blown away by Reeves. I thought that he was right up there with literary spouses like June Miller or Zelda Fitzgerald. He was a fantastic writer and we don’t have anything he wrote except for letters, and what you can tell from them is that he found a bazillion different ways to tell McCullers he loved her. They’re really inventive, really smart.

Then there’s the whole separate question about the so-called proof of McCullers being a lesbian. She loved women, she fell in love with women, she wanted to sleep with women. Whether or not she really did, who knows? Even if we believe it happened, what would we define as a “sexual relationship”? It becomes absurd, you know? Willa Cather’s biographer has had to contend with something like this, and she put it really well: Willa Cather and Edith Lewis lived together their whole lives. What more do you want? Photographs?

These questions are hard as a biographer, because we don’t know, and then I start asking, “Does it even matter?” It starts to call everything the biographer does into question. But I guess I can live with that. The issue of queerness is fundamental to how she lived her life and to how she worked out her novels.

Marlon Brando (back) and Elizabeth Taylor in the 1967 film adaptation of Reflections in a Golden Eye, directed by John Huston (Warner Bros. / Photofest)

LOA: Thinking of the characters McCullers wrote about, her interest in outsiders and non-heteronormative relationships, where did that come from? Are there biographical facts that we can point to as the genesis of her thinking around this?

MVD: It must happen before she starts writing. The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter comes almost full-blown out of her head. And where did all those strange people come from?

Part of it must be living in the south, living in a small southern town and having a very active imagination. The people she saw on the street who might not seem that weird to you or me just seemed particularly odd to her. She got a bead on them. She talks about being taken as a kid to some houses where poor people lived and looking inside a sort of cottage, a cabin, and describing what she saw in it. These things had a great effect on her, maybe more so than on most people.

She fell in love with her piano teacher when she was about thirteen. McCullers knew that there was something about their relationship, because strangely, the piano teacher kind of loved her back. I’ve come across this woman’s correspondence in later life and she was deeply weird. But the teacher was married and was not going to get involved with a thirteen-year-old girl.

Carson McCullers in 1959 (Carl van Vechten / Library of Congress)

McCullers had said she wanted to be a concert pianist. And that’s what this piano teacher, who was very well-trained and accomplished herself, and who had an in at Juilliard, would tell her: “You can go there if you want to be a concert pianist.”

There’s one character in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter based on McCullers—it’s pretty obvious—who wants to be a composer. She didn’t want to be a concert pianist! She wanted to be Beethoven or nothing. She didn’t want to just play the piano, no matter how brilliant she’d be.

In the end she was betrayed by the piano teacher in the way that only a thirteen-year-old feels betrayed. I think the teacher’s husband got transferred to another city and McCullers felt her leaving was a betrayal, and therefore she decided she wasn’t going to play music anymore. Instead, she would become a writer.

When she moved to New York, it’s not clear whether she was still going to attend Juilliard and take writing classes on the side. But pretty quickly she had decided writing, not music, and piano went by the boards.

LOA: McCullers had many literary and artist acquaintances. Can you talk about some of her more formative or influential relationships?

MVD: She fell in with a really interesting crowd. New York must have been like a phantasmagoria to her. She lived in a house in Brooklyn Heights with Paul Bowles and Richard Wright and W. H. Auden and Gypsy Rose Lee. That’s one of her novels come to life, really. She must have felt like she’d come to the feast.

“February House,” 7 Middagh Street in Brooklyn Heights, where McCullers lived in the early 1940s (Brooklyn Historical Society)

The people that house attracted were pretty extraordinary. She met all the Manns: Klaus Mann and Erika Mann, and then Golo Mann came to live in the Brooklyn house. And then you throw in the middle of that the poet Muriel Rukeyser, also among that group though only a visitor to the Brooklyn house. McCullers is right in the middle of this hive of people.

This sounds very naïve for a biographer, but looking back on this period, none of these people were famous then, so they didn’t know, for example, “Oh, Muriel writes poems.” It was just an odd little bunch of people. They didn’t draw inspiration from each other the way that fully mature artists might. But in a more pure way, McCullers learned from them.

When she went to live in Nyack, New York, it was like a Bohemian suburb. There’s this whole area around there, Rockland County, and especially New City, where all these actors and playwrights and artists lived. McCullers must have fit right in, and it must have been this incredibly fascinating landscape.

There is a guy named George Davis who lived in the house in Brooklyn with her, who worked at Redbook and Glamour, back in the glory days when women’s magazines were the best places for fiction. Davis brought some of these people together and took McCullers out to Rockland County. Kay Boyle was among the people she met there, and so was Hortense Calisher. To me, this was a new cross section of American literature, American arts, that I didn’t know about.

LOA: Another close relationship of hers that has an LOA connection is Tennessee Williams. They’re both southerners, they share an eye for the bizarre, the grotesque.

MVD: There’s a really strong connection there. There’s the southern thing, absolutely. But I think they recognized in each other that they were not run-of-the-mill southerners. They weren’t racist, they were appalled at the south’s past, and they didn’t quite know what to do about it. When they met, right away they started talking about the role that the N-word had played in their lives, and they each had an appalling story to tell about it.

It wasn’t the content of their discussions after that so much. They spent several weeks on Nantucket together, each writing every day, which apparently was not very like them. If they were alone, they might put in the hours on the typewriter, but if they were in any kind of social situation, writing would not come up. McCullers kept getting crushes on neighboring women, and Williams was there with his boyfriend at the time, Pancho Rodríguez y González.

Ethel Waters and Julie Harris in the 1952 film adaptation of The Member of the Wedding, directed by Fred Zinnemann (Columbia Pictures / Photofest)

LOA: Could you talk about how McCullers’s writing on race was received by Black critics or writers? There’s Richard Wright, who praised her treatment of Black characters. How successful do you think she is in taking on this topic?

MD: The first Black character in McCullers that I remember is in The Member of the Wedding, and I guess you’d call her a housekeeper. The three main characters in that book are Berenice, the housekeeper, Frankie, the girl, and John Henry, the neighboring boy. So it’s two children and Berenice, and it’s set in the kitchen and outside under the scuppernong arbors. You have a very typical southern setting, and what seems like this Black nanny, Black mammy stereotype. But it’s not that at all.

Berenice is way more complicated. There are no visible adults in The Member of the Wedding except Berenice. There’s the suggestion that adults are just not very reliable, they’re very shadowy, and Berenice is the real moral and thematic center, the kind of emotional wellspring for the rest of the characters.

I think there’s a similar sort of bursting at the seams with any seemingly stereotypical Black character in McCullers’s work. I’m thinking of Clock Without Hands, where one of the most emblematic things is that the young Black character has blue eyes. I think what McCullers is saying is, “Don’t be reductive.” That’s what Berenice is saying to Frankie and John Henry, too.

McCullers’s final three stories, which focus on race, are worth reading if you overlook the weakness of the fiction, because what she’s trying to do is interesting—going beyond what we might think of as stereotypes, the traditional ways that Black and white people are represented. Human beings are a lot more complicated than our colors and it’s time that we try to understand each other.

LOA: How central are illness and alcoholism to understanding McCullers’s art and biography?

MVD: It’s so central. She had strep throat when she was little, and before there were antibiotics, this could often develop into rheumatic fever, which can lead to all kinds of heart problems, but also stroke. And in her case, it did. She was pretty much stricken by thirty, and by the time she was forty, she was in pain almost all the time. It became harder for her to walk and get around.

Meanwhile, she came from a family of alcoholics. Reeves was an alcoholic, also from a family of alcoholics. But because McCullers was so adored in her family, nobody ever said a word to her about her drinking, even though she had a sister in Alcoholics Anonymous.

Especially when she started having strokes, the drinking and the illness became really related: she’s in pain, she drinks to help it. Of course, everything is made worse and it becomes this horrible ball of calamities. It sort of snowballed—not out of control, but it conspired to keep her from doing her best work.

McCullers in 1961 (Ben Martin / Getty Images)

Maybe I should state the obvious, which is that it killed her: her alcoholism and her strokes led to an early death. It cut short her career. Her last novel, Clock Without Hands, she really wrote that in blood. There’s a distinct falling off in her work toward the end, and also in her sense of commitment to who she was. She always saw herself as a writer, and that’s how she defined herself, but it didn’t come first. Living, trying to get through the day and making sure her alcohol needs were met—those came first.

It’s always tragic when somebody who’s an artist or a writer gets derailed by alcohol. But at the same time, it’s interesting to think of McCullers in that great American literary tradition of drunks: Hemingway and Fitzgerald. And yet we don’t put her on that list, and I think it’s interesting why not. We don’t really accommodate the idea of a female alcoholic in our vision of American literature.

WATCH: Suzanne Vega on Her Love of Carson McCullers at LOA’s 40th Anniversary Gala

LOA: There is so much writing and art about McCullers: the 1975 biography, the tributes to her like Jenn Shapland’s My Autobiography of Carson McCullers and Suzanne Vega’s Lover, Beloved: Songs from an Evening with Carson McCullers. Why write a new biography of her now?

MVD: There are very intense personal responses to McCullers; that’s what she awakens in people. I might sound like a recovering academic, but I still think there’s some value in writing a traditional, cradle-to-grave biography of her, because the one that we have is from 1975. And it’s excellent, but the woman who wrote it, Virginia Spencer Carr, didn’t have access to any of McCullers’s papers. There were no archives yet, the materials hadn’t reached their homes. Carr was a really good reporter. She talked to everyone alive. It almost becomes an oral history of primary sources. Pretty much everyone she talked to was dead by the time I wrote my book, but I had the papers.

I think there’s a need for a modern Carson McCullers biography so we have the facts out there. Those of us who respond to her in a very personal way will have an idea of the truth behind who we’re responding to.

Mary V. Dearborn is the author of seven books, including biographies of Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer, and Carson McCullers. She received a B.A. in English and Classics from Brown University and a Ph.D. in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University, where she was a Mellon Fellow in the Humanities. She was most recently a fellow at the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. She lives in Buckland, Massachusetts.