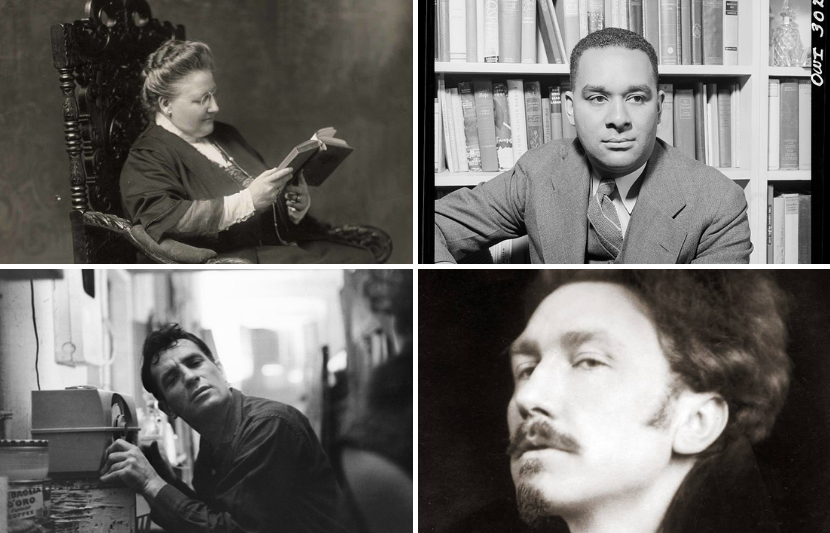

Amy Lowell on the cover of Time magazine in 1925 (Public Domain), Richard Wright (Library of Congress), Ezra Pound (Public Domain), and Jack Kerouac (John Cohen/Getty Images)

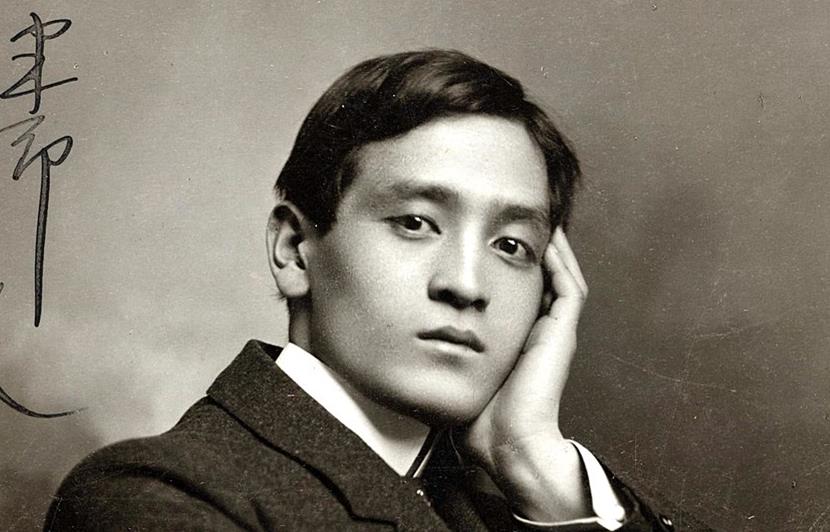

Nestled in the middle of National Poetry Month in April is a day dedicated to one of the most enigmatic and bewitching forms of verse: the haiku. Originating in Japan in the 17th century, these mini-compositions comprising three phrases of five, then seven, then five syllables got their stateside debut in 1904, when the pioneering transnational writer Yone Noguchi urged, in the pages of The Reader Magazine, “Pray, you try Japanese Hokku, my American poets! You say far too much, I should say.”

Yone Noguchi, photographed in 1903 (Public Domain)

The Americans got the message. Ezra Pound’s verbless 1913 poem “In a Station of the Metro,” though not structured like a traditional haiku (it has two lines and nineteen syllables), drew influence from the Japanese form and indicated a new direction for English-language poetry, away from Victorian verbosity and toward a minimal yet exacting observation and evocation of place.

In a Station of the Metro

by Ezra PoundThe apparition of these faces in the crowd:

Petals on a wet, black bough.

But it was Amy Lowell, fellow Imagist of Pound and posthumous winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1926, who pushed American experimentation with haiku past its dalliances with exoticism and Orientalist emulation. As Bruce Ross writes in an essay for the Haiku Foundation, Lowell “captured the qualities inherent in the haiku beyond the current fashions for Chinese and Japanese art and poetry.” Short works of hers like “Autumn Haze,” “The Pond,” and “Nuit Blanche” “[express] a sensitivity of feeling and compression of a moment’s experience.”

from Twenty-Four Hokku on a Modern Theme

by Amy LowellI

Again the larkspur,

Heavenly blue in my garden.

They, at least, unchanged.II

How have I hurt you?

You look at me with pale eyes.

But these are my tears.III

Morning and evening—

Yet for us once long ago

Was no division.

Though perhaps more often associated with logorrheic streams of “first thought, best thought,” to use Allen Ginsberg’s phrase, the Beat generation embraced the pithy precision of haiku in the years following World War II. Jack Kerouac was a dedicated practitioner, yielding a corpus of some 1,000 pieces and even declaring an autochthonous American variant of the form, which he named “Pops.”

Blues and Haikus, a studio album featuring Kerouac alongside tenor saxophonists Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, came out in 1959—and it’s actually pretty great! (Allmusic.com, in a four-and-a-half-star review, calls it “a stunning duet between speaker and saxmen, working spontaneously in this peculiar mix of jazz and voice.”)

Gary Snyder, “poet laureate of Deep Ecology,” was unabashed in naming haiku’s impact on his art. Granted the Grand Prize at the 2004 Masoaoka Shiki International Haiku Awards, he noted, “the influence from haiku and from the Chinese is, I think, the deepest.” And in Kerouac’s 1958 novel The Dharma Bums, the Snyder stand-in Japhy Ryder gives a practical tutorial in haiku during a hike up Matterhorn Peak in California:

“Look over there,” sang Japhy, “yellow aspens. Just put me in the mind of a haiku. . . . ‘Talking about the literary life—the yellow aspens.’”. . . . We made up haikus as we climbed, winding up and up now on the slopes of brush.

Matterhorn Peak in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California (Public Domain)

It’s a heroic image, these two Beat icons trailblazing toward the mountaintop, swapping impromptu poems under sweaty circumstances. Yet the delicate work of haiku could also be accomplished closer to home, in sickness and decline as in vigorous ascent.

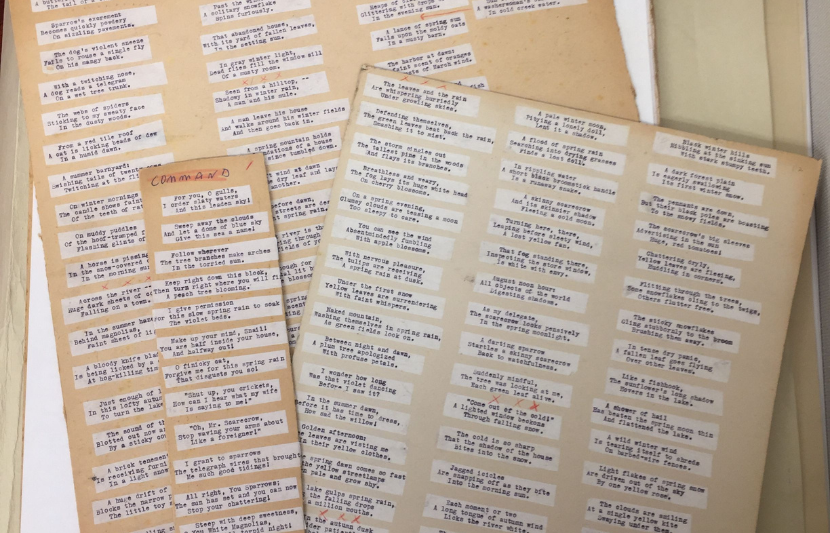

The novelist Richard Wright wrote an estimated 4,000 such poems in the last years of his life. “He was never without his haiku binder under his arm,” recalls his daughter Julia Wright in her introduction to Haiku: The Last Poems of an American Icon, a compendium of his work in the genre.

For the Native Son author, the daily habit of haiku-writing acted as a bulwark against his failing health. Julia Wright goes on to describe her father’s commitment to the practice:

My father’s law in those days revolved around the rules of haiku writing, and I remember how he would hang pages and pages of them up, as if to dry, on long metal rods strung across the narrow office area of his tiny sunless studio in Paris, like the abstract still-life photographs he used to compose and develop himself at the beginning of his Paris exile. I also recall how one day he tried to teach me how to count the syllables: “Julie, you can write them, too. It’s always five, and seven and five—like math. So you can’t go wrong.”

Herein lies the thrilling paradox at the heart of American haiku: the strictness, the “law” of the form Wright describes, leads counterintuitively to a unique kind of expressive freedom. If Pound and Lowell leveraged haiku to escape the fussy, overstuffed tendencies of much turn-of-the-century poetry, then Wright, beset by illness, similarly recognized a type of liberation in the genre’s rigor. “I believe his haiku were self-developed antidote against illness,” Julia Wright contends, “and that breaking down words into syllables matched the shortness of his breath.”

Sample of haiku by Richard Wright (Beinecke Library, Yale University)

Haiku, in its brevity and restraint, reminds us vividly of the fragility and transience of life. In its compression and focus, however, we see the strength and beauty of all that is small and unassuming. Sometimes the mountain we’re climbing is as tall as the Matterhorn; other times it’s three lines and seventeen syllables long: magnificence and majesty in miniature.

Interested in getting more articles on literature and history before they’re published on our website? Sign up for our e-newsletter and e-mail promotions (we’ll never spam you or share your e-mail with any other company).