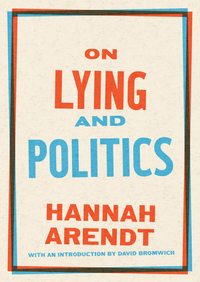

We Are Free to Change the World: Hannah Arendt’s Lessons in Love and Disobedience by Lyndsey Stonebridge (Hogarth, 2024)

Hannah Arendt is one of our most enduring and provocative moral and political theorists. A refugee from fascist Europe who made her second home in America, she astutely perceived the promises and contradictions of her adopted country: its professed love of freedom alongside its virulent history of racism; its revolutionary origins alongside its colonialist and warmongering activities abroad; and its veneration of the individual alongside its pressures toward conformity and anti-intellectualism.

In order to break these reactionary links, Arendt declared, “We are free to change the world and start something new in it.” Taking these exhortatory words as her springboard, author and scholar Lyndsey Stonebridge investigates the resonances and applications of Arendt’s philosophy to our own fraught political moment in her new book, We Are Free to Change the World: Hannah Arendt’s Lessons in Love and Disobedience (Hogarth, 2024). This new volume “details the life and thought of Hannah Arendt in ways that speak to our troublesome times,” says Princeton professor Eddie S. Glaude, Jr. “We get a sense of the expansiveness of Arendt’s thought—her vulnerabilities and her complexity—with stories and intimate details that reveal Stonebridge’s love of her.”

Below, Stonebridge talks with LOA editorial director John Kulka about how to read Arendt in the twenty-first century, the émigré writer’s ambivalence about America’s political future, and why thinking—especially thinking done by women—can be uniquely dangerous.

Hannah Arendt (The Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities)

LOA: To start, could you talk about why you’ve written this book, and why now?

Lyndsey Stonebridge: I have been reading Hannah Arendt since I was a student in the 1980s, but over the past few years her work has become more relevant than any of us could have imagined then. Her key themes speak to us now with a desperate new urgency—bewilderment, cynicism, impunity, violence, loneliness, the suffering of people whose lives have been deemed superfluous. She thought hard about all of these things, and thinking, too, was an important motivation for writing this book. There is a really important lesson to be had from how Arendt responded to her times: with realism, integrity, imagination, courage and, perhaps above all, an abiding love of the world.

LOA: Early in your book, you say reading Arendt isn’t just an intellectual undertaking, but an experience. Your own book, similarly, seems to be an invitation to read with, alongside, and sometimes against Arendt—and, by extension, with, alongside, and against the book in hand. How do you envision readers using your book?

LS: Arendt says that as soon as you think of someone as a “character,” you start describing “what” they are and lose a sense of “who” they are. That “who” is vitally important in Arendt’s thinking. I didn’t want to write a conventional biography. There are so many stereotypes about women thinkers that assume we know what “type” they are. Arendt suffers from these stereotypes more than many; it’s hard not to hear the misogyny in some responses to her work, even now. So instead, I set out to have a conversation with Arendt, what she would call a “two-in-one dialogue.” And yes, I hope that readers can in turn enter into that conversation: learn, contribute, interrupt, dispute, and disagree (all Arendtian qualities!).

LOA: You characterize Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem—drawn from her series of articles in The New Yorker covering Adolf Eichmann’s televised trial in Israel in 1961—as a broadside against moral relativism and an attack on ethical posturing. Might your own book be characterized the same way?

LS: I sincerely hope so. We tend to debate in absolutes and abstractions today. Ours is a culture of shame and outrage. There is plenty to be outraged about, and plenty to be scared about. But the outrage and shame feeds into a political and media cycle that, to put it mildly, is neither helpful to political morality nor conducive to democracy. Worse still, it prevents us from properly engaging with real questions of guilt. “When all are guilty, no one is,” Arendt said. “Confessions of collective guilt are the best safeguard against the discovery of culprits, and the very magnitude of crime the best excuse for doing nothing.”

She saw that the events of the twentieth century had profoundly damaged political morality. This could not be put right by recourse to old philosophical tools or newly imagined certainties—they were no longer there. Instead, she said, we need to learn to think without a banister. That is Arendt’s challenge.

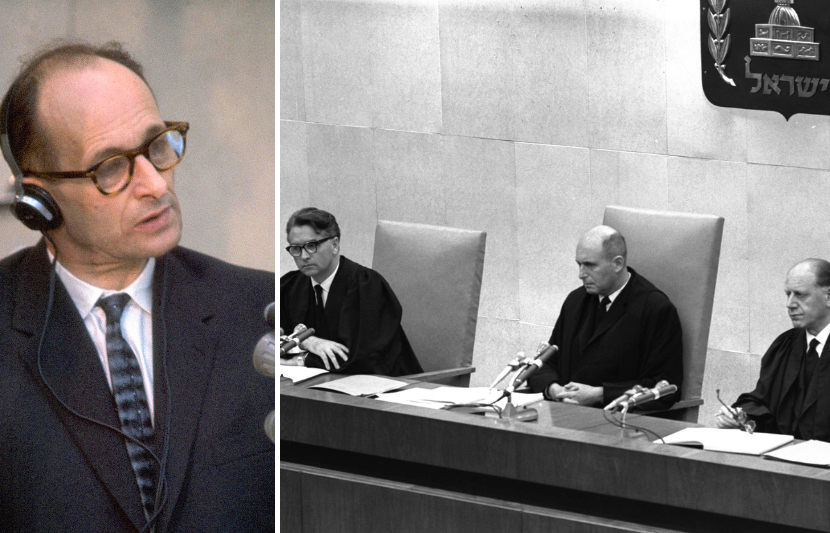

Adolf Eichmann on trial in 1961 and trial judges Benjamin Halevy, Moshe Landau, and Yitzhak Raveh (Public Domain / Israel National Photo Collection)

LOA: Let’s talk a little more about Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust. Arendt portrays him as a kind of mindless or unthinking bureaucrat, utterly detached from reality (for example, during his trial, he quoted from Kant and informed his judges that he planned to write a book on the difficult philosophical and historical nature of his guilt). Could you comment on Eichmann’s prominence in your book, how he comes in and out of the discussion and crisscrosses Arendt’s life at crucial junctures?

LS: Eichmann was catastrophically thoughtless, and we need to appreciate how serious this is. Just because he was banal did not mean he was not evil. He really was.

It’s also important to note that Eichmann himself deliberately played the part of a simple, if especially diligent, bureaucrat—he thought this was his best chance of winning the Jerusalem court over (which in a way also demonstrates how unthinking he was: the courtroom was full of survivors). Arendt’s point is that he played the part of an evil Nazi with about the same depth, which is to say, no depth at all. And what really is terrifying is the fact that he calmly administered the Holocaust without thinking about what he was doing, without seeing, hearing, or imagining the reality of what he was participating in.

It’s true, too, that Arendt is probably best known for her controversial book on Eichmann. But I hadn’t realized how biographically close Arendt and Eichmann were. They were born within seven months of each other. As she fled Germany, becoming a stateless person, detained in a camp, hiding out, and finally making it to America, Eichmann rose in the Nazi party and began organizing the genocide against the Jews. As she thought more—thinking was Arendt’s mode of survival—he thought less.

I wanted to juxtapose their lives to show that, actually, Arendt did know Eichmann far better than people sometimes imagined. Her visit to the trial was intensely personal. She couldn’t live with herself, she wrote to a dear friend before going to Jerusalem, without going to look at this “walking disaster” (Eichmann) face-to-face. What she found in Jerusalem was a very modern sort of demon: a vain, self-important man, murderously indifferent to the reality in which everyone else lived.

Arendt in 1950 (Public Domain)

LOA: One of Arendt’s most-quoted phrases is, “There are no dangerous thoughts; thinking itself is dangerous,” from her 1971 lecture “Thinking and Moral Considerations.” What does having a free mind mean in Arendt’s sense, and why can it be so perilous?

LS: Thinking is an activity. We all do it—not all the time (otherwise we’d never get anything done), but a lot. Thinking is where we have a conversation with ourselves, where the voice in our head troubles, delights, and perplexes us. In other words, thinking is how we connect to ourselves.

This is what makes thinking a moral activity, too. We all have to live with ourselves, and, as Socrates said, who wants to live with a liar, a murderer, or a villain? Thinking is also how we encounter the perspectives of others, as we train ourselves to go visiting other positions and minds. In this sense, thinking is a gateway to forming judgments about the world: is this right or wrong, true or false, ugly or beautiful, good or bad? It is on the basis of these judgments that we might act, and that is what makes having a free mind dangerous in Arendt’s view—dangerous to those who wield their power by dominating our minds, and dangerous, too, to the thinker whose actions might well require courage.

LOA: Public thinking by women, you say, is especially dangerous. Why is that?

LS: I think Arendt herself speaks to that! I still find it shocking just how much opprobrium she attracts. Some of that is because she dared to speak her mind, much of it because she did so brilliantly and uncompromisingly, and quite a bit of it because she was not afraid of displeasing her readers or listeners (although she was never controversial just for the sake of it).

Although she never commented publicly on feminism, she was well aware of the kinds of reaction thinking women attracted. One of her heroines was the revolutionary economist Rosa Luxemburg, who also went out on a political limb. Luxemburg was murdered; having her own mind proved to be not only dangerous but fatal. When Arendt tells the story of how the men who killed her laughed during their trial, you can really feel Arendt’s bitter anger. This was violent misogyny writ large. But you won’t stop women thinking—and acting—dangerously. There are several examples in my book in addition to Arendt and Luxemburg, such as Elizabeth Eckford, who courageously walked up to the doors of a segregated school and then through a racist mob when she was refused entry. More recently, there are the women of Iran, Afghanistan, Belarus, Ukraine, Palestine, and Israel: women who refuse to stop thinking—and sometimes acting incredibly courageously—whatever the consequences.

The Spartacist uprising in Berlin on January 1919 (Alfred Grohs / CC BY 3.0) and Rosa Luxemburg in 1915 (CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

LOA: Arendt is a philosopher of definitions and categories, but she is not, as you point out, a builder of philosophical systems in the way that, say, Hegel is said to be. In fact, the more time one spends with Arendt’s books and essays, the more aware one becomes of her continual turning away from certainties and comfort zones. Can you say something about that, and how this connects with Arendt’s persistent desire to remain unknowable herself?

LS: Arendt makes distinctions, not exclusions, and she does this because she is committed to understanding how a plural world works and, importantly, working out how we can best preserve and honor that plurality. So yes, she likes categories, because they allow us to see clearly. She also thinks it’s important to observe distinctions, such as between our private, social, and political lives, and between laboring, working, and acting.

The privacy point is crucial. It’s true that Arendt wanted to remain unknowable, but she also knew that we are all unknowable, to ourselves at least. A world of fully transparent people would be a true nightmare.

Arendt’s outsider-stranger perspective was central to her thinking: who, for example, can see the decline of the nation state better than the person who has had their citizenship revoked? Who knows love, companionship, and friendship as well as the refugees and camp inmates who only have one another?

LOA: Hannah Arendt’s statelessness—she called herself an “illegal émigré”—wasn’t merely incidental to her political thought and writings, and you link her to other outsiders through their shared refugee or pariah’s viewpoint. Heinrich Blücher, Rahel Varnhagen, Walter Benjamin, Kafka, Rosa Luxemburg—these were her intellectual companions. What is it about refugee status that makes it an advantageous viewpoint for observing the domain of political life?

LS: No one, she says in an early study, knows the rain better than the person who is stuck outside without an umbrella. Arendt’s outsider-stranger perspective was central to her thinking: who, for example, can see the decline of the nation state better than the person who has had their citizenship revoked? Who knows love, companionship, and friendship as well as the refugees and camp inmates who only have one another? Who knows the frailty and beauty of the human condition more intimately than the person who has nothing else? This was a constant theme in her work.

Arendt and Mary McCarthy (Public Domain)

LOA: In a letter to Arendt, her friend Mary McCarthy called Arendt’s 1951 masterpiece The Origins of Totalitarianism as “engrossing and fascinating” as a novel. Taking your cue from McCarthy, you describe Origins for your readers as the story of how millions of twentieth-century Europeans came to live a murderous ideological fiction. But it’s a story that is more prosaic and tawdry than what we might think. Can you explain?

LS: When you think of totalitarianism, you think of marching boots, windowless torture cells, constant surveillance, industrial terror, and murder. The story Arendt tells about how this came about in the twentieth century, for the most part, is more familiar: technological advance, huge wealth divides, imperialism, racism, antisemitism, the rise of nationalism, political lies, ludic conspiracy theories, inchoate hatred and fear.

Her point is that monstrosities do not come out of nowhere. Elements conspire to create the conditions for the seemingly impossible to become hideously possible. To read The Origins of Totalitarianism today is to be gripped, exactly as you are by a great novel, by an awful sense of inevitability, and a powerlessness to change the ending. This does not mean, of course, that we cannot change our own endings. We are free to change the world, remember. But first we have to comprehend what is really happening.

LOA: Let’s talk about love. Arendt’s interest in love as a subject of intellectual inquiry dates back to her PhD dissertation on Saint Augustine. “Volo ut sis” (“I want you to be”) is one of your favorite Arendt remarks. Can you expand on that? And Arendt also admonishes us not to love too much. Why is that?

LS: This comes both from her reading of Augustine and from her experience as a refugee and camp inmate. It is my favorite remark of hers, you’re right, both for its simplicity but also for its context. In the middle of The Origins of Totalitarianism, talking about radical rightlessness, she suddenly writes:

This mere existence, that is, all that which is mysteriously given us by birth and which includes the shape of our bodies and the talents of our minds, can be adequately dealt with only by the unpredictable hazards of friendship and sympathy, or by “the great incalculable grace of love, which says with Augustine, ‘Volo ut sis’ [I want you to be]” without being able to give any particular reason for such supreme and unsurpassable affirmation.

It’s a beautiful passage, this mere existence that can only be answered by the unconditional love of others.

Arendt loved well. She didn’t worry too much about loving too much in our personal lives. What scared her was the kind of politics conducted in the name of love (or any other grand emotion). It was in the name of the love of man that the French Revolution unleashed terror. A genuinely loving politics, for Arendt at least, has to be vigilant about its limits, compromises, and workings-through.

First-edition cover of The Origins of Totalitarianism (Schocken Books, 1951)

LOA: Arendt had a genuine love for America, her adopted country. In a lovely turn of phrase, you say she “loved America for its love of beginnings.” Can you explain?

LS: “In the beginning was America,” wrote the philosopher John Locke in his defense of colonialism. Arendt, although more clear-eyed about the price paid for that beginning by the people who had lived on the continent for centuries before, agreed. Fleeing from a Europe demolished by fascism, nationalism, and absolutism, Arendt saw in America the origins of a political system that guarded freedom, particularly freedom through action, from its very beginning.

She experienced this, too. Upon arriving in the United States, she observed the community engagement of her hosts in New England and was impressed, not to say surprised. I don’t think people know how forcefully the sense of an entitlement to freedom in America can hit the newcomer, even today. Europe is an old continent, which lost its audacity (let alone its hope) a long time ago. Arendt knew that slavery—America’s “great crime” in her words—had wrecked its promise from the beginning. But she also thought that the potential was always there for something else, even as, by the time she died in 1975, political mendacity and violence threatened that legacy in ways that, as we see again today, could well yet be fatal to the American experiment.

LOA: Arendt worried, however, that mass society and corporate capitalism had diminished Americans’ freedom and power—a fear very much present in 1963’s On Revolution. But the civil rights movement and the antiwar movement during Vietnam seem to have rekindled her hope that our history of voluntary association could still be a life force in American politics. These hopes find keen expression in her essay “Civil Disobedience,” published in Crises of the Republic (1972). There, she calls civil disobedience a uniquely American invention and considers whether it should be enshrined in the Constitution. Did she want to connect civil disobedience to our prerevolutionary history of voluntary association? And how did she view the struggle for Black rights in connection with this history?

Clockwise from top left: the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, 1963 (Public Domain), Tea Party protest in Hartford, CT, 2009 (Sage Ross / CC BY-SA 3.0), antiwar protest in Washington, D.C., 2007 (Ragesoss / CC BY-SA 3.0), and Occupy Wall Street in New York City, 2011 (David Shankbone / CC BY 3.0)

LS: Arendt saw in civil disobedience not just a matter of personal conscience, but a commitment to the collective assent (and dissent) central to the political and legal contract. This is what made group action so vital: if the law is ceasing to work for people—if government is using the law to overstretch it limits—breaking that law is a way of bringing power to account. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, under the shadow of endemic racism, nuclear proliferation, Vietnam, and criminality at the heart of government, the stakes for civil disobedience could not be higher. She called that generation of activists “the generation that could hear the ticking,” and haven’t events proved her right?

The civil rights movement was a brilliant example of how Americans act to keep America true to its original promise: promises would be kept; the Fourteenth Amendment would be made to work. In her essay on “Civil Disobedience” which, I agree, is compulsory reading for today, she argued for “an explicit constitutional amendment” to be addressed to Black Americans that would acknowledge the crimes against them and ensure future rights.

But just as Arendt had some good ideas about America’s racial politics, she also had some very bad ones. Her misreading of the desegregation battles of Little Rock in the late 1950s is a case in point. Arendt liked the idea of enacting civil rights in order to claim them, but as America became more chaotic in the late 1960s and early 1970s, she was bothered by Black power, which she often cast as violent. At best, I think of this as “purse-clutching”—President Obama’s description of the passive-aggressive treatment of Black people in elevators in his Trayvon Martin memorial speech. Arendt was always deeply worried about revolutionary violence; that was the refugee from fascism in her. But she didn’t always correctly identify where the real violence was coming from, and that, perhaps, was the new American citizen in her.

Lyndsey Stonebridge is a professor of humanities and human rights at the University of Birmingham (UK) and a Fellow of the British Academy. Her previous books include Placeless People: Writing, Rights, and Refugees, winner of the Modernist Studies Association Book Prize and a Choice Outstanding Academic Title; The Judicial Imagination: Writing After Nuremberg, which won the British Academy Rose Mary Crawshay Prize for English Literature; and the essay collection Writing and Righting: Literature in the Age of Human Rights. She is a regular media commentator and broadcaster, and lives in London and France.