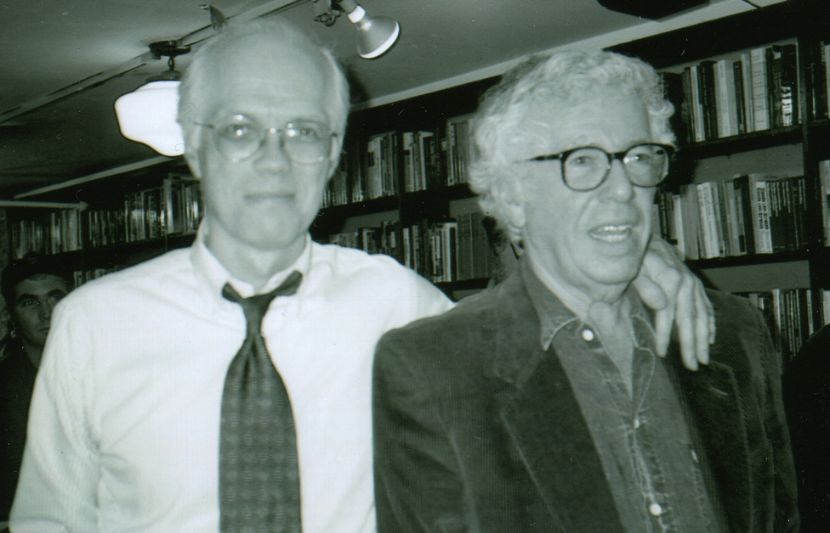

Ron Padgett and Kenneth Koch in 1996 (photo courtesy of Ron Padgett)

An American iconoclast who elevated humor and scythed down stodginess in his poems, Kenneth Koch’s body of work resonates with “the mystery and pleasure of being alive,” says Ron Padgett, celebrated poet, translator, and editor of the LOA edition of Koch’s Selected Poems.

On the occasion of Koch’s centennial this winter, Padgett spoke with LOA editorial fellow Francisco Márquez about his longstanding friendship with the revered New York School writer, the hidden rewards of Koch’s persistently surprising verse, and upcoming events honoring the legacy of this American literary titan.

LOA: Thank you, Ron, for taking the time to speak about your work and about Kenneth Koch, whose centennial was last month and will be celebrated at the New School with a legendary crew of poets, writers, filmmakers, editors, and artists. In what other ways are you celebrating Koch’s centennial this year, and what does this occasion represent for you? Also, for those readers who are less familiar with Koch’s work, where would you suggest they start?

Ron Padgett: The Kenneth Koch Literary Estate has helped plan a number of celebrations of the centenary of his birth: the event at the New School, a Kenneth Koch online book club, a display dedicated to him at the New York Public Library (which houses his huge archive), a marathon reading of his poetry at Columbia University, readings and panels in Great Britain, France, and Italy, evenings of his plays, and events featuring his collaborations with composers and visual artists.

As his friend and admirer, I’m extremely pleased to see the spotlight on him. As for readers who are less familiar with his work—poetry, fiction, theater, and writings on poetry—I’d suggest starting with the poems in the LOA edition of his Selected Poems. After that, there is the rest of his writing—a vast amount of it—to look forward to.

LOA: I’m struck by how your curation in the Selected Poems captures Koch’s evolving style, as well as a range of tones—from humorous to instructive to meditative, often all at once. How did you go about choosing which poems to include, and what were you looking to illustrate to readers about his work and legacy?

RP: In selecting the poems for that volume, I was helped by [Kenneth’s wife] Karen Koch and the poet and editor Jordan Davis. The three of us drew up separate lists of our favorites, and when we compared them we found a surprisingly big overlap. Then I ran the combined list by the poet and critic David Lehman for his suggestions. The general idea was to create a succinct survey of the entire range of Koch’s poetry, from start to finish, though we didn’t have room to include his long poems.

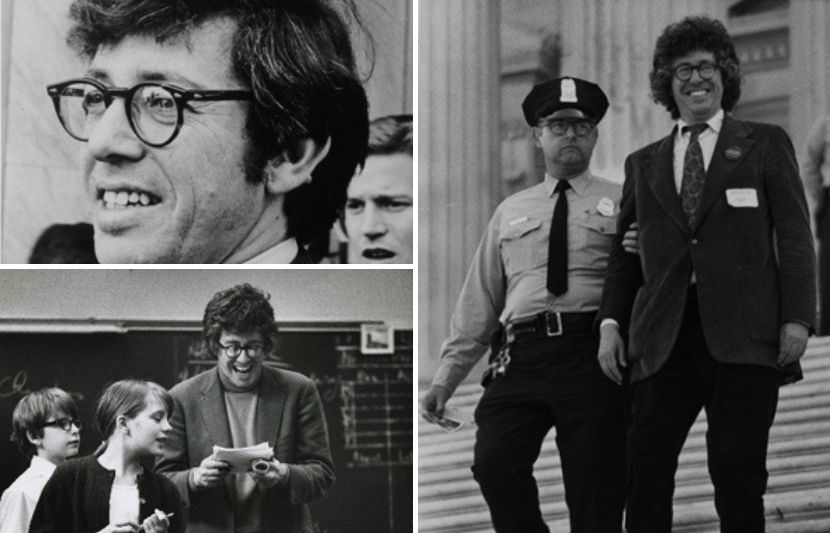

Clockwise from top left: Kenneth Koch in the 1970s, Koch at the March on Washington in 1969, and Koch teaching at PS 61 in New York City, 1968 (kennethkoch.org)

LOA: I admire how, in the collection’s introduction, you characterize Koch’s changing relationship to writing poetry, especially toward the end, saying he didn’t confuse awards with greatness and “continued to vie happily with his literary heroes past and present.” How did Koch’s outlook on the relationship between life and poetry affect your own outlook on this balance?

RP: For Kenneth, life and the writing of poetry were, as he put it, mostly the same thing. That is, he wasn’t someone who wrote and thought about poetry only occasionally. It was intrinsic to everything he did, and his ambition was to live well and to write well. His example inspired a lot of younger writers over the years, including me. He not only pointed us toward the work of writers we’d never heard of, he also radiated an enthusiasm and optimism about reading that work and writing our own poetry. From the age of sixteen I decided I was going to be a poet, but Kenneth confirmed my decision. He took me seriously.

Kenneth was just about the only American poet starting out in the early 1950s who dared to allow humor into his work.

LOA: I’m moved by the origins and development of your relationship with Kenneth. How did his mentorship, and subsequent friendship, affect your own relationship with mentorship and community in poetry? How do you view this aspect of the writing life relating to the mostly solitary act of writing poems?

RP: First, Kenneth was my teacher at Columbia—I took every class I could from him—and then my mentor, and then my friend and collaborator, as well as my tennis buddy. He got me grants (one when I was desperately broke, and one that gave me a free year in Paris). Kenneth was a sort of second father, always looking out for me. I’ve tried to follow his example, but I’m not as generous as he was. However, with his help, I did teach poetry writing to children for a number of years, especially at an elementary school in my neighborhood, the school he wrote about in his trailblazing Wishes, Lies and Dreams. Working with the local kids and teachers, I began to feel, for the first time in my life, that I could actually be useful as a poet. And it was fun bumping into my students at the local supermarket or in the street and have them tell their parents, “That’s Mr. Poetry!” They outed me.

Listen: Kenneth Koch Lectures on Poetry

LOA: I couldn’t conduct an interview with you without discussing your incredible translations of Guillaume Apollinaire’s poems, published by New York Review Books. It was through your translations that I came to discover Apollinaire’s work, and I love how they capture the rhymes, the inherent rhythms, and the surprisingly contemporary tone of his original poems. How has the act of translation changed or informed the writing of your own work?

RP: I’ve never been sure how to answer that question, but I can say that translating, for me, involves having words fly and float around in my mind, bumping up against each other and creating resonances. Also, translating someone’s work is, I think, the closest way that one can read it—so close that I’ve had times when I temporarily imagined I was Apollinaire or Cendrars or Reverdy. Nutty, no?

Anyway, Kenneth once told me that when he had a dry spell (which was a rarity), he liked to translate, to keep his hand in, as he put it. And, by the way, it was Kenneth who got me into translating.

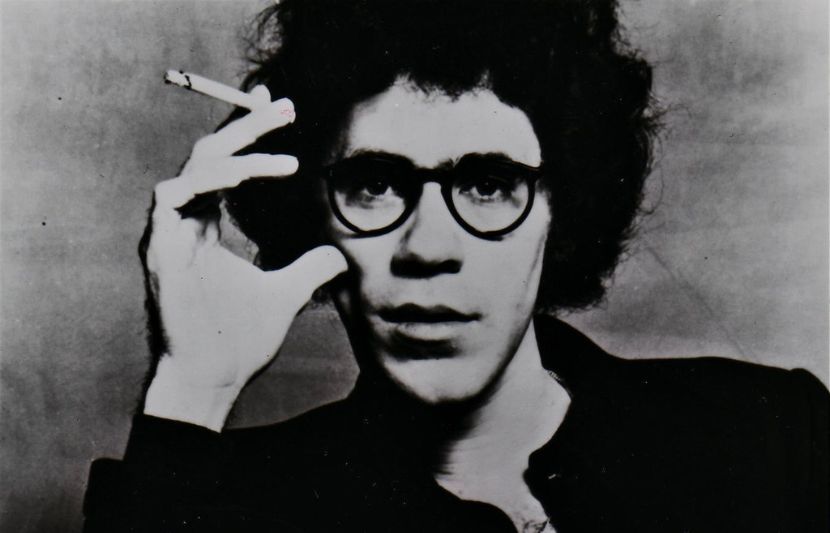

Publicity photo of Joe Brainard, 1970 (photo: Wren de Antonio)

LOA: Finally, another iconic New York poet who comes to mind when reading Koch’s work is Joe Brainard, whom I know you were friends with since high school. His whimsical, earnest, and often humorous lyricism reminds me at times of Koch’s own sensibilities. What role do you see humor and playfulness having in the poetry of that era, and why do you think it was so prominent? What place do you see it having in poetry today?

RP: Kenneth was just about the only American poet starting out in the early 1950s who dared to allow humor into his work. It was a very high, imaginative, witty, and ultimately serious humor, so in reading it you laughed and then you were flooded with the pleasure and intelligence of it. But Kenneth was dismayed when people pigeonholed him as a “funny” poet.

In any case, I think he and Joe had very different sensibilities. Joe was a naif who found a way to make it a strength. He was, as Paul Auster pointed out, a total original, with no direct influences, whereas the comic in Kenneth’s work came, at least partly, from Aristophanes, the medieval play Everyman, Henry Fielding’s Tragedy of Tragedies, or the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great, Henry Carey’s Chrononhotonthologos, Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, Lord Byron’s Don Juan, and Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi, to name just a few.

In general though, during the 1960s especially, playfulness was in the air in non-academic circles. Look at Kenneth’s poem “Fresh Air” and you’ll see what I mean.

Ron Padgett is the author of many books of poetry, including How to Be Perfect, You Never Know, The Big Something, How Long, and Great Balls of Fire, as well as Joe: A Memoir of Joe Brainard. He edited, for Library of America, the American Poets Project edition of Kenneth Koch: Selected Poems.