From The Great American Sports Page: A Century of Classic Columns

There is a scene in The Great Gatsby when Nick Carraway has lunch with Meyer Wolfshiem and Jay Gatsby and learns that Wolfshiem is the man who fixed the 1919 World Series.

“Meyer Wolfshiem? No, he’s a gambler.” Gatsby hesitated, then added coolly: “He’s the man who fixed the World’s Series back in 1919.”

“Fixed the World’s Series?” I repeated.

The idea staggered me. I remembered, of course, that the World’s Series had been fixed in 1919, but if I had thought of it at all I would have thought of it as a thing that merely happened, the end of some inevitable chain. It never occurred to me that one man could start to play with the faith of fifty million people—with the single-mindedness of a burglar blowing a safe.

“How did he happen to do that?” I asked after a minute.

“He just saw the opportunity.”

“Why isn’t he in jail?”

“They can’t get him, old sport. He’s a smart man.”

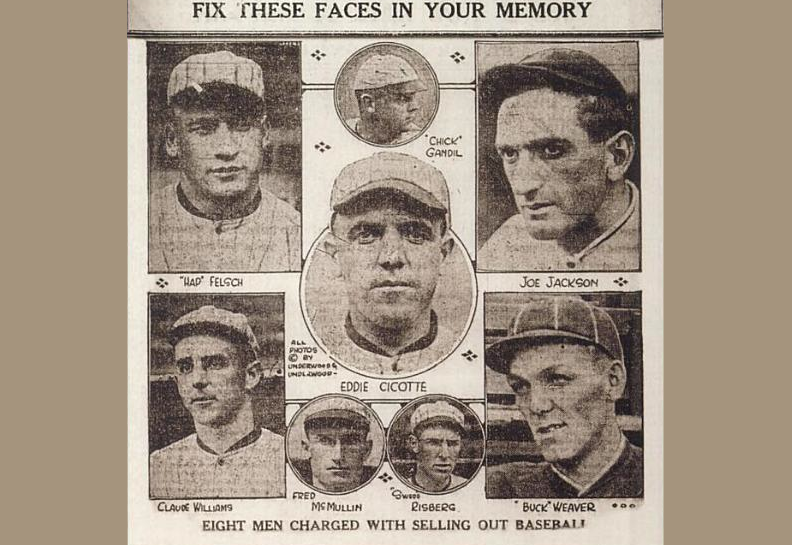

Readers at the time would have known that Wolfsheim’s character was based on racketeer Arnold Rothstein, who caught wind of the “fix” and won $300,000 as a result. He was convicted only in the court of public opinion, however, since there is little evidence of any direct role in the plot (which originated with the players). Prosecutors at the time cleared him of any involvement.

Jonathan Yardley, in his biography of Ring Lardner, suggests that this scene has all the markings of Lardner’s influence. Fitzgerald was 26 and Lardner 37 in 1922 when the two men became friends and, later, neighbors in Great Neck, New York. Fitzgerald was the new boy wonder of the literary scene, with four books published in three years, while Lardner, a longtime baseball writer and perhaps the most famous humorist in America, had published twelve books of columns, sports reporting, and baseball tales but had not collected any of the non-baseball short stories that had appeared in magazines. Fitzgerald took it upon himself to act as Lardner’s quasi-agent, introducing him to Maxwell Perkins, his own editor at Scribner’s, and arranging for the stories to be published in the collection How to Write Short Stories (with Samples). (Both Perkins and Fitzgerald were flabbergasted when they found out Lardner had not kept any copies of his stories, many of which had been published in The Saturday Evening Post.) Lardner returned the favor by proofreading and fact-checking The Great Gatsby.

“They talked sports, probably many times, for Ring was an authority and Scott, in that enthusiastic way of his, a fan,” Yardley writes. “That at some point or another they talked about the 1919 World Series and Ring’s feelings about it seems not only probable but certain. That their conversation inspired Scott to use that Series as yet another symbol of corruption in a novel filled with such symbols certainly is within the realm of possibility.”

For Lardner, the 1919 World Series and the Black Sox scandal that tainted it were two of several events that, like his friendship with Fitzgerald, transformed the nature of his writing. Even so, it is probably an exaggeration to claim, as many do (and he himself sometimes did), that the scandal permanently soured him on writing about baseball. For our Story of the Week selection, then, we present Lardner’s humorous “report” of the first game of that series, along with an introduction that describes Ring’s knowledge of the scandal and what role it played in changing the course of his career.

Read Ring Lardner’s “Kid’s Strategy Goes Amuck as Jake Doesn’t Die”