By Nicole Rudick

In January 1969, thirty-two-year-old Joanna Russ attended a four-day conference on “Women Today,” held at Cornell University’s College of Human Ecology. The meeting was organized by Sheila Tobias, who had arrived in Ithaca from City College in New York only two years earlier as the new assistant to the vice president for academic affairs. Tobias was struck by the overwhelming chauvinism at the Ivy League institution. “The faculty is not coed; the administration is not coed,” she observed. Out of some 1,400 faculty members, only a hundred were women.

Images from the Cornell Conference on Women, January 1969 (Cornell University)

When Tobias was asked to offer support for classes between academic terms, she saw an opportunity. With the help of an organizing committee, she devised a conference that wasn’t simply about exploring employment opportunities available to women (since there were so few), but about investigating the psychological and sociological questions on which women’s perceptions of themselves were based.

Sheila Tobias in 1972 (The Knoxville News-Sentinel)

“We started with the assumption that the woman’s problem is not a woman’s problem; it is a social problem,” Tobias wrote. “There is something wrong with a society that cannot find ways to make it possible for married women, single women, intelligent women, educated or uneducated, or welfare women, to achieve their full measure of reward.” Some two thousand people attended discussions on abortion, contraception, childcare, race, and sexuality. It was one of the first conferences in the United States to address sexism in an academic setting.

Russ had arrived at Cornell in 1967 as a writing instructor, though she’d attended the university as an undergraduate, matriculating in 1957 at age twenty. Russ didn’t yet consider herself a feminist, but she was well aware of compulsory femininity and what, late in life, she would call “the most idiotic minutiae of patriarchal ideology and behavior.”

In high school, she was selected as a top-ten finalist in the Westinghouse Science Talent Search. She was the only woman. In a formal portrait from the awards ceremony in Washington, D.C., Russ, swaddled in tulle, sits in the front row, flanked by nine boys and three older men in suits and tuxedos. Nearly all of them have turned to look at her—a directive from the photographer, perhaps, but a move that nonetheless singles out her difference and gives the image a strange, wolfish tension. The tableau recalls the poet Carolyn Forché’s description of the midcentury American poetry scene: “I looked at photographs, formal group portraits of American poets, poets such as Howard Nemerov, W. H. Auden, Robert Lowell. And often in these portraits, there would be a woman seated in a small chair in the front of the group, and most of the poets would be standing or leaning casually against desks surrounding her.” In Forché’s telling, there is only ever one chair, only one woman.

Russ seated with other Westinghouse Science Talent Search finalists in 1953 (Society for Science)

Russ later recalled that her studies as a student at Cornell reflected “a profound bias about what was proper material for ‘Great Writing.’” Later, in science fiction, she found a means to express the gap between the reality of the world around her and a desire to change that reality; it was a genre in which “the conceivable was far larger than the personally observable.” In the months before the Cornell Conference, she published four stories about Alyx, the tough, time-traveling pickpocket from Ourdh who, in every incarnation, outwits her adversaries with a combination of intellect, cunning, and fighting prowess. These are adventure stories “about a woman in which the woman won,” Russ later said. “It was one of the hardest things I ever did in my life.”

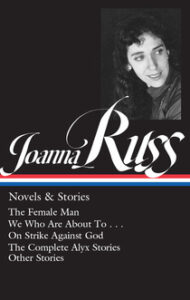

Cover art for The Adventures of Alyx by Joanna Russ (Timescape Books, 1983)

Still, the conference took her by surprise. “My first reaction upon hearing Kate Millett speak . . . was that of course every woman knew that but if you ever dared to formulate it to yourself, let alone say it out loud, God would kill you with a lightning bolt.” Russ wasn’t the only one dumbfounded by the proceedings. “It was the first time feminism had hit Ithaca,” she said. “Marriages broke up; people screamed at each other who had been friends for years. It absolutely astonished me. The skies flew open.” The anger Russ witnessed was clarifying: a few weeks after the conference, she wrote “When It Changed.”

The story, only some 3,400 words, opens with a car flying down a pitted country road at night. The narrator, riding in the passenger seat, remarks on the daring of the driver—“my wife,” Katy—and on the youthful bravery of their eldest daughter, Yuki, asleep in the backseat, “dreaming twelve-year-old dreams of love and war.” The narrator was brought up on a farm and refuses “to wrestle with a five-gear shift at unholy speeds,” but, unlike Katy, isn’t afraid to handle guns. A reader could be forgiven for perceiving the narrator as a man—Russ doles out male-coded details throughout this initial portrait—but as the car reaches its destination, the crisis they’ve been speeding toward is wholly unexpected: “‘Men!’ Yuki had screamed, leaping over the car door. ‘They’ve come back! Real Earth men!’”

Not only did [Russ] write books and stories that she would have liked to read as a girl, struggling with her gender and sexuality, but also ones that unrelentingly held American society, as well as the science fiction community, to account for its inequities and hypocrisy.

This is Whileaway, where a plague six hundred years ago wiped out the male of the species. And now, suddenly, four men have arrived, from another planet or from the past. “They are obviously of our species but off, indescribably off,” Janet, the narrator, observes. “My eyes could not and still cannot quite comprehend the lines of those alien bodies.”

The shift from past to present tense in Janet’s rejection of these strange physiques foreshadows what the reader learns by the end of the story: with the arrival of these men, the world of women is forever changed. There is no going back to the imperfect though no less Edenic life reimagined by women, one where their ancestors’ “long cry of pain” resides only in historical accounts. Janet observes the men’s size and strength (“muscled like bulls and who made me. . . feel small”), their condescension and implication of sexual exploitation. Through this commentary, Russ hints at the threat of violence men pose to women. The people of Whileaway have developed technology for merging ova in order to produce offspring, but the men cannot fit this profound biological change into their traditional way of thought. They don’t simply want a donation of eggs, they want to revert to the “natural” way of producing offspring—a proposal, in this context, akin to rape.

“When It Changed” does not conjure a utopia: the women war with one another (Janet has fought three duels) and disagree politically in a nascent industrial state where the population must labor for three-quarters of their lives, devoting themselves to art only in their later years. But they organize and endure on their own terms. “A great tragedy,” one of the male interlopers says condescendingly of the loss of his sex, “but it’s over.” His decisiveness is chilling. “Men are coming to Whileaway,” Janet concludes, resignedly, as she thinks about centuries of freedom coming to an end. The new men reassure the women of Whileaway that “sexual equality has returned,” but few, if any, are in doubt that what’s soon to return are the old tyrannies. The yearning of Whileaway’s inhabitants in “When It Changed” is an embodiment of the lines from Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas: “As a woman I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman, my country is the whole world.”

Shulamith Firestone circa 1970 (Michael Hardy)

Much feminist writing in the late 1960s—and specifically in 1969—rooted the perpetuation of a gender caste system in heterosexual marriage and biological determinism, or the belief, as Dr. Spock advocated in Redbook in March 1969, that women are “made to be concerned first and foremost with child care, husband care, and home care.” At the same moment Russ was furiously writing “When It Changed,” Shulamith Firestone was completing her radical study The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, published in September 1970. Firestone, too, wrote urgently, completing the book in a matter of months. Firestone describes the fifty-year gap between the end of first-wave feminism and the beginning of what would come to be called the second wave as an era in which women’s class solidarity and political power were fractured. Women were, as Firestone put it, “reprivatized”—a situation that resonates with the one on Whileaway. In both cases liberated women find themselves incorporated back into patriarchal systems as components to be exploited.

Firestone argues that feminism is a response “to the development of a technology capable of freeing women from the tyranny of their sexual-reproductive roles—both the fundamental biological condition itself, and the sexual class system built upon, and reinforcing, this biological condition.” The ova-merging technology on Whileaway is just that kind of development; both Janet and Katy conceive and carry babies. For the newly arrived men, however, this advancement looks like nothing more than “a good economic arrangement. . . for working and taking care of children.” So much for the return of sexual equality.

At the story’s end, Russ leaves the future open, though not necessarily undecided. Janet thinks about her distant ancestors, who changed the name of their planet to Whileaway after the plague that killed the men, and finds it “amusing, in a grim way, to see it all turned around. This too shall pass. All good things must come to an end.”

“When It Changed” reads as a response to traditional science fiction stories in which a man saves a woman from an alien menace. In Russ’s telling, it is the men who assume the role of alien invaders. The circumstances for women on Whileaway came about not through revolt but necessity. Yet now their situation mirrors that of the women who attended the Cornell Conference—radicalized by chauvinism and aiming to fight back.

Portrait of Russ (Tee Corinne / Lesbian Herstory Archives / University of Oregon Libraries)

“When It Changed” is an apt title for this turning point in Russ’s life. It marks the beginning of her lifelong engagement with the fight for women’s liberation and equality, the banner under which her subsequent writing, beliefs, and actions would align. The latent threats in the story reverberate in nearly all of her fiction, criticism, and feminist essays. Not only did she write books and stories that she would have liked to read as a girl, struggling with her gender and sexuality, but also ones that unrelentingly held American society, as well as the science fiction community, to account for its inequities and hypocrisy.

Gay Liberation Front poster, 1970 (Peter Hujar)

Russ didn’t know she was a lesbian when she wrote “When It Changed.” She had “kind of come out” at age eleven, but found no models in literature or in life through which to understand her attraction to women. The subject was taboo. Much fiction that portrayed lesbian life ended in tragedy. Russ herself had written such a story around age fifteen—a tale of two lesbians that culminates in suicide.

About six months after the Cornell Conference, she attended a Gay Liberation Front lecture, and some of her students were there. Two of them announced they’d been lovers for years. Russ left the meeting “on cloud nine, thinking, it’s really possible. It can be done.” She walked outside “into the most luminously beautiful June Twilight I’ve ever seen, and saying to myself over and over, that Lesbianism was real, that people really did it, and that I wasn’t the only one and I hadn’t invented it.” The lecture proved a catalyst. Russ found that “When It Changed” had “started growing all the apparatus” for a novel.

First-edition cover of The Female Man (Bantam Books, 1975)

That novel was The Female Man, her highly influential tale about four versions of the same woman—Jeannine, Joanna, Janet, and Jael—from different dimensions and times. Janet gathers Jeannine and Joanna from their worlds (an alternate New York in 1969, where the Depression never occurred, and a 1969 Earth that resembles ours, respectively) to her own, on the Whileaway of “When It Changed.” From there, they travel to the dystopian Womanland, Jael’s home, where a war between men and women has waged for forty years. Faced with Janet and Jael’s radically different realities, Jeannine and Joanna see their own societies, and their place in them as women, anew. But Janet, who has transformed herself into a “female man” in order to escape the confines of femaleness, resists reimagining her role, and her lament late in the novel conjures the “long cry of pain” of Whileaway’s ancestors:

I love my body dearly and yet I would copulate with a rhinoceros if I could become not-a-woman. There is the vanity training, the obedience training, the self-effacement training, the deference training, the dependency training, the passivity training, the rivalry training, the stupidity training, the placation training. How am I to put this together with my human life, my intellectual life, my solitude, my transcendence, my brains, and my fearful, fearful ambition? I failed miserably and thought it was my own fault. You can’t unite woman and human any more than you can unite matter and anti-matter; they are designed not to be stable together and they make just as big an explosion inside the head of the unfortunate girl who believes in both.

Publishing The Female Man was, for Russ, “a great freeing of a whole lot of energy and relief. I could address my own life and the situation I was in straightforwardly.” It was as if the novel occurred to her the moment she realized she could be a free woman and a lesbian in the world—just as her introduction to feminism in January had brought forth her story “When It Changed.” She wrote to the poet Marilyn Hacker about The Female Man: “It’s not what it should be, but it’s the way I feel and the way it is—the Man hasn’t disappeared & I can’t vanish him away.” Russ was prepared for a heated response to the book. “Once they dismiss you, they have a sigh of collective relief,” she told Hacker. But she wasn’t going to be dismissed or ignored, and with The Female Man, she put the world on notice. She described the novel in plainer terms: “It’s not shrill, it’s ultrasonic.”

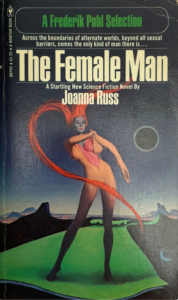

Nicole Rudick is the author of What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined: An (Auto)biography of Niki de Saint Phalle. Her essays on art, literature, and comics have been published in The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Artforum, and elsewhere. She is the editor of the LOA edition of Joanna Russ: Novels & Stories.