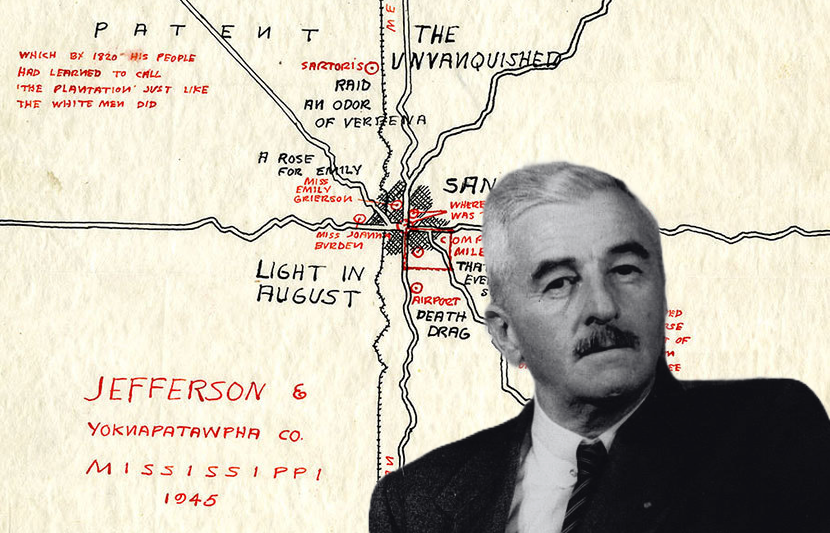

Detail from 1945 map of Yoknapatawpha that Faulkner drew for The Portable Faulkner (Brodsky Collection, Center for Faulkner Studies, Southeast Missouri State University / Digital Yoknapatawpha) and Faulkner in 1954 (Carl Van Vechten / Library of Congress)

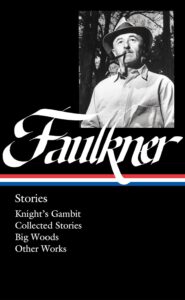

In the pantheon of American writers, few figures loom larger than William Faulkner, whose peerless evocations of the south and its people achieved immortality in such classic novels as The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, and Light in August. But Faulkner maintained a special reverence for the challenges and possibilities of the short story, which he called “the most demanding form after poetry.” From the exploits of savvy country lawyer Gavin Stevens in Knight’s Gambit to the haunting hunting narratives of Big Woods, the recently published volume of Faulkner’s stories caps LOA’s six-volume edition of the author’s oeuvre—a testament to one of the most remarkable (and re-readable) accomplishments in our nation’s literature.

Over e-mail, Theresa M. Towner, a leading Faulkner scholar and editor of William Faulkner: Stories, discussed the myriad dimensions of the author’s intricate fictional universe: the creation of Yoknapatawpha County, stage of so many Faulkner dramas; what the writer thought of his work’s oft-cited “difficulty”; and the representations of race and racism that root his work in the brutal daily reality of the Jim Crow south. What emerges is a portrait of a consummate artist, irreducible in his complexity and outspoken in his vision, who when he accepted the Nobel Prize in 1950 would say that the award “was not made to me as a man but to my work—a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before.”

LOA: The majority of Faulkner’s fiction takes place in Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, inspired by the writer’s own Lafayette County (he called it his “little postage stamp of native soil”). How do you think about Yoknapatawpha as a holistic fictional creation? How do the stories flesh out this setting in comparison with the novels?

Theresa M. Towner: I don’t think that Yoknapatawpha County unifies or explains Faulkner’s work; I think that Faulkner’s work explains Yoknapatawpha. In fact, the fictional county exists only in Faulkner’s fictions, but because it does, it can also live in our imaginations. In this sense it is completely transferable—transient and always in transition, analogous to the “motion” of life itself.

“The aim of every artist is to arrest motion,” Faulkner said, “which is life, by artificial means and hold it fixed so that 100 years later when a stranger looks at it, it moves again since it is life.” Faulkner’s short stories add more motion and more life to pages that are lifeless until a reader moves them, and that’s a paradox he would’ve appreciated.

It’s also worth noting that Faulkner never bothered to make Yoknapatawpha consistent. A character might have a brother in one novel and fifteen brothers and sisters in another; a river might be in a different location among texts; distances between places might vary. Yoknapatawpha County isn’t even named until the publication in 1930 of As I Lay Dying.

Rowan Oak, Faulkner’s home in Oxford, Mississippi (Library of Congress)

LOA: The three collections in this volume—Knight’s Gambit, Collected Stories, and Big Woods—encompass all the short fiction Faulkner gathered in his lifetime. What is the significance of each manuscript in Faulkner’s career? How do they differ in terms of theme, style, and subject matter?

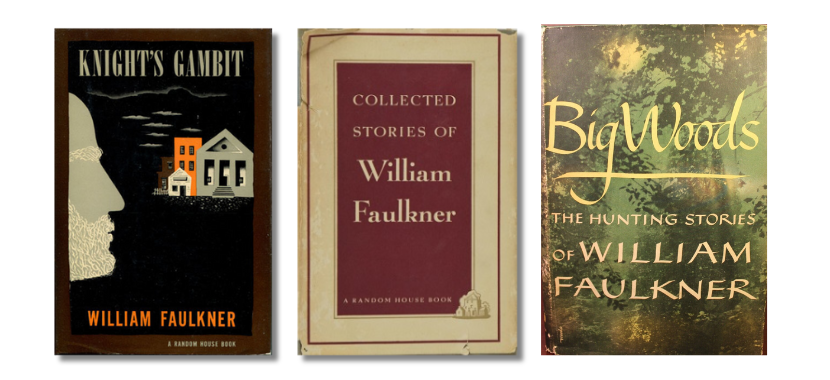

TMT: Faulkner actually produced five short story volumes: These 13, Doctor Martino and Other Stories, Knight’s Gambit, Collected Stories, and Big Woods. All of the short stories in the first two volumes appear in Collected Stories, except for “The Hound” from Doctor Martino [which the LOA edition includes in an “Other Works” section]. Faulkner chose and arranged the contents of each volume, and he had definite ideas about how to do that. While working on These 13, he said that “a book of short stories should be linked together by characters or chronology,” and that book is divided into three parts. The first contains Great War stories; the second, stories set in Yoknapatawpha County; and the third, stories set in far-flung international venues.

The idea for a volume of collected stories came from Faulkner’s editors at Random House, but he enthusiastically accepted it and set to work to produce a long book with six sections that kept related stories together: “The Country,” “The Village,” “The Wilderness,” “The Wasteland,” “The Middle Ground,” and “Beyond.” During the production of this volume, he got the idea to do a separate collection of short stories featuring attorney Gavin Stevens and his forays into detective work; the result was Knight’s Gambit, which contains six previously published stories and a new novella of that title to show how Gavin’s work as a detective ultimately resulted in his marriage.

Big Woods contains revised versions of several Faulkner stories associated with hunting—including what he called “interrupted catalysts” to link them. It’s notable that not only animals are prey in these hunting stories and that material from previously published sources was used or revised in order to fit into this new project. Faulkner omitted section four of “The Bear” from the collection because it belongs in the McCaslin family history and not Ike’s experience in the big woods, and he likewise changed “Delta Autumn” into a lament for the woods sacrificed to human rapine and waste. He very much enjoyed making that new collection and wrote to a friend that “I had thought that perhaps with A FABLE, I would find myself empty of anything more to say, do. But I was wrong, another collected, partly rewritten and partly new book this fall, and I have another one in mind I shall get at in time.”

Faulkner was a deliberate craftsman of perspective and point of view, and he was interested too in how and why people tell stories of all kinds and for all kinds of reasons—to gain, to exploit, to defend, to entertain, to protect, to attack.

This career-long involvement with story collections shows us that Faulkner was always trying to find ways to “make it new,” as Ezra Pound said art should do, even when the new work of art had its own past. It’s also interesting to see what he did not include in collections. Only Big Woods contains stories that he had revised into novels, for instance. Other collections did not include them, which probably explains why “The Hound” didn’t go into Collected Stories; Faulkner had significantly revised it for The Hamlet.

LOA: The Faulknerian sentence—labyrinthine, layered, often quite long—can be both a source of delight and frustration for readers. In a Paris Review interview, Jean Stein asked the author, “Some people say they can’t understand your writing, even after they read it two or three times. What approach would you suggest for them?” “Read it four times,” was Faulkner’s testy response. What do you think Faulkner is trying to do with this difficulty? What lies behind this challenge to readers to pay closer attention?

TMT: Faulkner once wrote to the literary critic Malcolm Cowley, “I am telling the same story over and over, which is myself and the world.” His contemporary Thomas Wolfe “was trying to say everything. . . in one volume,” but “I’m trying to say it all in one sentence, between one Cap and one period.” That effort led, he thought, to “what people call the obscurity, the involved formless ‘style,’ endless sentences.”

He did not write to exclude readers—in fact, he didn’t think about us at all when he was working—but to include material relevant to his characters and their own experiences with the world. Sometimes that made for long sentences, as it does in novels like The Sound and the Fury that represent emotional inner turmoil and confusion. The same novel opens with a section made up of simple, short sentences representing the inner life of an adult man who has extremely limited verbal ability but profound emotional distress, and it also contains a section narrated by a smart and talkative pathological liar.

1924 publicity photo of Faulkner (Public Domain)

I should add that Faulkner’s short stories contain fewer of those labyrinthine sentences than do the novels, precisely because the form is more concise. He called it “the most demanding form after poetry” and well understood how to meet those demands. A story like “Carcassonne” represents a conscious mind on the verge of sleep, death, or both, and contains very little physical motion; its five pages are dense, confusing, and challenging. By contrast, a story like “Shingles for the Lord” uses long sentences to create literary still-shots of moments of frenetic action, such as when a church unexpectedly explodes into flame.

LOA: A number of stories—notably “A Rose for Emily”—are told from what seems to be a group perspective, using “we” and “our” pronouns, never situating the narrator in a single person’s point of view. What does this collective voice accomplish—or obscure—compared to the close third-person of, say, “Barn Burning” or Quentin’s narration in “That Evening Sun”?

TMT: In the case of “A Rose for Emily,” the group narrative perspective obscures what Emily is doing because the townspeople, like Emily’s father, don’t think that Emily is any different from what they expect an aging white spinster to be. For them, she’s gossip material and not much more. This obscuring is a kind of accomplishment, just as Quentin’s narration obscures what happened to Nancy in favor of revealing his own family’s complicity in her victimization.

The narrative focus on Sarty Snopes in “Barn Burning” reveals the terrible consequences of a child’s victimization at the hands of a powerful and domineering father, who is not wrong about the racial basis of the economic forces in the south. Sarty is too young, too powerless, to understand his father, but the narrative perspective allows Faulkner to cast ahead into his future to reflect on the precarious position of his nine-year-old self. Faulkner was a deliberate craftsman of perspective and point of view, and he was interested too in how and why people tell stories of all kinds and for all kinds of reasons—to gain, to exploit, to defend, to entertain, to protect, to attack.

LOA: Faulkner has a keen interest in the thoughts and experiences of children, frequently homing in on the gulf where adult and childhood understandings of the world diverge. And though Faulkner empathizes with children, depicting their subjugation to the capricious and hurtful whims of adults, he also shows them as consequential actors in their families and communities, capable of cruelty, moral injury, and grave misjudgment. What does Faulkner’s focus on children—as characters, narrators, inheritors of history—tell us?

TMT: Faulkner’s children are evidence of his abiding interest in humanity’s obsession with power. Like the central character of “Barn Burning,” children have “the terrible handicap of being young, the light weight of his few years, just heavy enough to prevent his soaring free of the world as it seemed to be ordered but not heavy enough to keep him solid footed in it, to resist it and try to change the course of its events.”

First-edition covers of Knight’s Gambit (Random House, 1949), Collected Stories (Random House, 1950), and Big Woods (Random House, 1955)

Yet even the handicap of youth can be exploited for gain, as when Georgie of “That Will Be Fine” plays dumb for a lawman in order to help his Uncle Rodney out of a jam, for which Georgie will be paid in the quarters he so dearly loves. At one point he extorts Rodney for more money, and he unknowingly sets up the circumstances for Rodney’s death at the hands of one of his marks. Faulkner shows us some ugly adult realities through Georgie’s naïve first-person narration. The children in his fictions can, and do, choose how to treat other people, and they are no more or less ignorant of what motivates them than Faulkner’s adults are.

LOA: Race is a central presence in Faulkner’s fiction, which is almost all set in the era of Jim Crow. Faulkner himself was ambivalent on desegregation, inviting criticism from James Baldwin. At the same time, Ralph Ellison said, “No one in American fiction has done so much to explore the types of Negro personality as Faulkner.” To what extent does Faulkner counter or complicate the dominant narratives around Black-white relations in the American south of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century? What context or caveats would you offer to readers interested in reading Faulkner through the lens of race?

TMT: I think it’s important to understand that no character or group of characters “speaks” for Faulkner on the topic of American race relations. As a private citizen or a public intellectual, Faulkner could not satisfy everyone interested in that subject during his own lifetime; he wasn’t liberal enough for Baldwin, and he wasn’t conservative enough for most of his neighbors in Mississippi. He himself knew that he could never inhabit Black life: “a white man can only imagine himself for the moment a Negro; he cannot be that man of another race and griefs and problems. So there are some questions he can put to himself but cannot answer.”

His fictions contain many representations of the inner lives of others, be they Black, male, female, white, mixed-race, old, or young. Always those representations bear witness to the artificiality of concepts like race, class, and gender; they are not “natural” conditions but culturally constructed categories that are deployed to the advantage of some and the disadvantage of others.

This is what Abner Snopes of “Barn Burning” has figured out when he talks about the racialized “sweat” that built plantations and currently powers the sharecropping system. A system of white supremacy gives Flem Snopes power over the Black workers Tom-Tom and Turl in “Centaur in Brass” until they compare notes on his behavior and devise a way to thwart his brass-stealing scheme.

Above all else, I’d remind readers that Faulkner knew that language itself can be an instrument of beauty and one of great destructive power. A story like “Dry September” shows how unwavering belief in the truth of one racial epithet removes a Black man’s individual identity, denies his place in humanity, and results in his death. The men who lynch him are hypocrites as well as murderers. They hide behind an ideology of racial supremacy that the story lays bare.

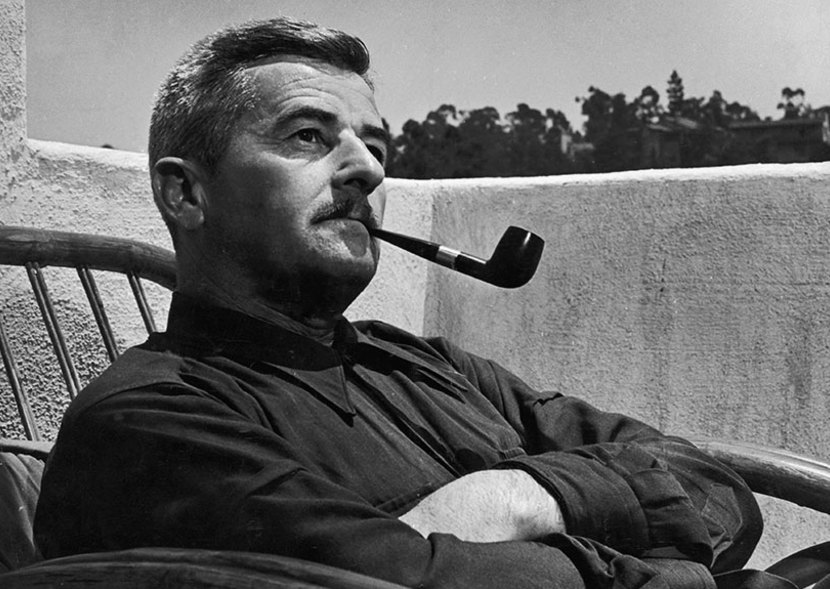

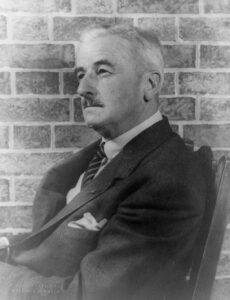

Faulkner in Hollywood in the early 1940s (Alfred Eriss / Pix Inc. / The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images)

LOA: Faulkner’s 1950 Nobel Prize acceptance speech is remarkable for several reasons: as a paean to humankind’s indominable artistic spirit, as a broadside against the apocalyptic absurdity of nuclear war, and as an interdiction against celebrating the life of the author in place of the author’s life work. What prompted Faulkner to tackle these subjects in his oration? Can you explain his seeming dismissiveness and skepticism toward the prize itself?

TMT: This question calls for speculation, since the records we have of Faulkner’s reaction to receiving the Nobel Prize are mostly fragmentary, appearing in letters and sometimes in other people’s memoirs. He seems to have known that he had been considered for it for several years before he won. The Nobel Committee awarded him the 1949 prize but didn’t confer it until December 1950 because the Committee did not reach the necessary unanimous vote until too late to award the Prize that year.

In letters we also see Faulkner working with the rhetorical phrases that appear in the speech. In 1948 he wrote about “the only book foreword I ever remembered,” which said “something like ‘This book written in . . . travail (he may have said even agony and sacrifice) for the uplifting of men’s hearts.’ Which I believe is the one worthwhile purpose of any book.” He initially declined to attend the ceremony in Stockholm, writing that “I hold that the award was made, not to me, but to my works—crown to thirty years of the agony and sweat of a human spirit, to make something which was not here before me, to lift up or maybe comfort or anyway at least entertain, in its turn, man’s heart. I feel that what remains after the thirty years of work is not worth carrying from Mississippi to Sweden, just as I feel that what remains does not deserve to expend the prize on himself, so that it is my hope to find an aim for the money high enough to be commensurate with the purpose and significance of its origin.”

His family and friends convinced him to attend the ceremony. He wrote the speech on hotel stationery and revised it slightly after its delivery. He didn’t comment much on the Prize, and one letter suggests that he may have been shoring himself up to save disappointment at not winning it: “I had rather be in the same pigeonhole with Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson.”

LOA: What stories in the collection are your favorites, and why? Given the number of pieces here, which ones would you recommend to Faulkner newcomers? How about hidden gems for the more experienced fans?

TMT: I don’t have any favorite stories in this book—or I should say that I have too many of them! Faulkner’s craftsmanship is breathtaking in so many ways that it’s hard for me to settle on a list of besties. “Mule in the Yard” and “Shingles for the Lord” end with one-line zingers that make me laugh every time I read them. “That Evening Sun,” “Dry September,” and “Wash” make me ache. “All the Dead Pilots” reminds me that every era has its own lost generation, and “The Leg” and “Carcassonne” leave me shaking my head in wonder at what is even going on.

Faulkner in 1954 (Carl Van Vechten / Library of Congress)

New readers of Faulkner can dip anywhere in the book and see what appeals to them. For readers who know only those folks in Yoknapatawpha County, a trip to “Golden Land” or a bit of “Black Music” or a look at soldiering in “Ad Astra” or “Turnabout” would be instructive. And everybody should read “Elly” and “An Error in Chemistry.”

LOA: Faulkner remains popular today, and not just because of his frequent assignment on American school curriculums (a 2009 French poll found him to be that country’s second favorite author after Proust). What explains his continued readership, nearly sixty years after his death? Are there aspects of Faulkner’s work that you think are especially relevant to contemporary audiences?

TMT: When people ask me why I continue to read Faulkner, I say that it’s because he tells the best stories. Students who like his work tell me that they can’t get his characters out of their minds; they keep thinking about a book or story after it’s over. (This is also true for people who don’t care for his writing, by the way.)

I think what we all mean by comments like this is that Faulkner texts create a very precisely drawn world inhabited by individuals with distinct personalities—not tropes or types, but specific people in a certain place having encounters with that place and with other individuals in that place. He doesn’t generalize about human experience; he creates and describes it. He doesn’t tell us what to think about what he shows; what he shows teaches us how to learn, to empathize, to interpret. Reading Faulkner teaches us how to read life, and audiences of all times recognize and benefit from that.

One of Faulkner’s typewriters (Gary Bridgman / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Theresa M. Towner holds the Ashbel Smith Chair of Literary Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas. She is the author of The Cambridge Introduction to William Faulkner and Faulkner on the Color Line: The Later Novels, co-author of Reading Faulkner: Collected Stories, and editor of Digitizing Faulkner: Yoknapatawpha in the Twenty-First Century.