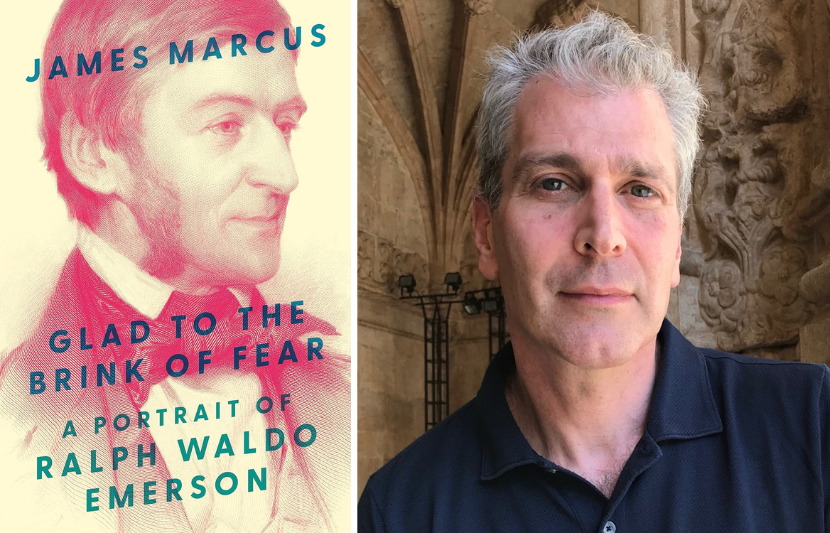

Glad to the Brink of Fear: A Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson by James Marcus (Princeton University Press, 2024)

Ralph Waldo Emerson was an overflowing font of words: essays, lectures, poems, and one of the most monumental journals in American letters. A public intellectual who preached the infinitude of private man, he befriended some of the leading literary lights of his day, abandoned the pulpit, and delivered 1,500 lectures across the country on a dizzying array of topics, from abolition to the philosophy of history. But who was the man who became the Sage of Concord, and what can his journey from spiritual seeker to transcendentalist figurehead teach us about the America we inhabit today—an America Emerson helped write into being?

In Glad to the Brink of Fear: A Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson (Princeton, 2024), author James Marcus sets aside the strictures and pieties of a strict cradle-to-grave biography to deliver a fresh perspective on the writer of “Self-Reliance.” Borrowing Emerson’s own tendency toward the discursive, the associative, and the obliquely interconnected, Marcus pairs a deeply researched account of Ralph Waldo’s life with close readings of his greatest works, deep dives into the pivotal moments of his career, and illuminating personal asides. “His Emerson is a marvel,” writes critic (and former LOA LIVE panelist) Merve Emre, “a skeptic and an apostle, a creature of flawed feelings and novel ideals, a lover, a mourner, a wit, and a visionary.”

Below, Marcus discusses his Emersonian odyssey, from browsing “Circles” late at night in search of emotional sustenance to finding the light amid his subject’s “bumper-to-bumper” sentences.

LOA: You seem to have a connection to Emerson that goes beyond just academic interest. Can you talk about the genesis of this book and what initially drew you to him?

James Marcus: I began to read Emerson intently twenty-five years ago, during a very challenging interval of my own life. I had a demanding job, a wife who was chronically ill, a child who was having problems—and at night, after they’d gone to sleep, I would find myself picking up a paperback of Emerson’s essays and reading a few pages of “Circles” or “Self-Reliance” or “Experience.”

I didn’t know much about Emerson, and at the beginning of my encounter with him, I found some of his work vexing, as many people do. It’s an old-fashioned idiom, he doesn’t bare his wounds very much, and the actual texture of his prose is not immediately familiar to a reader in 2024. But I must have been responding to something there, because I kept returning.

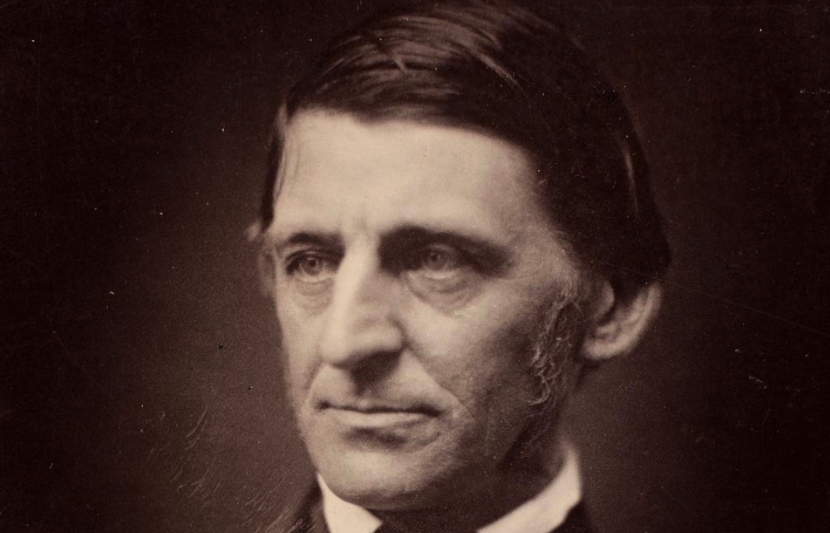

The next step was to learn more about the person, so I started reading biographies, and then, crucially, his journals and letters. Because he can be quite distant and starchy and elevated, I feel that the lovable part of his personality does not always spring out at a casual reader. But as you get used to his voice, there is something disarming and vulnerable that emerges.

1857 daguerrotype of Ralph Waldo Emerson by Josiah Johnson Hawes (Public Domain)

LOA: Even though Emerson’s essays famously wend in these discursive or even contradictory directions, what core ideas seem consistent throughout his life? Are there recurring preoccupations and interests despite his free-roving nature?

JM: I don’t really think of Emerson as a philosopher. His thinking is so anti-systematic that he would be shooting torpedoes into the hull of whatever philosophical system he tried to erect. To an extent, he thought that most philosophical and religious systems were straitjackets and the idea was to get out of them, not to make one for yourself and then for other people.

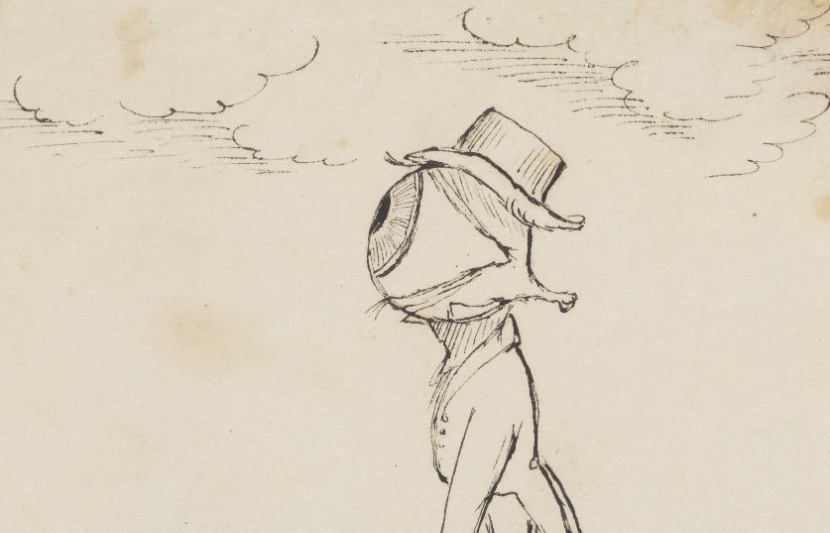

But despite that, there are ideas you find in almost all his writing. One of them has to do with what he called “the infinitude of the private man,” meaning that the individual, the subjective and intuitive self, could do all the heavy lifting in life and in your understanding of the universe. It was the self-reliant credo of: Do not turn to the church, do not turn to the old books or purveyors of wisdom, do not turn to the state. You should look at reality as if it has never been seen before. Examine it with your own eyes. Describe it in your own words. Rely on your instinct.

To me, that’s a beautiful thought. Still, there can be a downside to individualism and self-reliance, which is that it tends to shatter the bonds of community. In his life, Emerson came to understand that you were, in fact, inextricable from other people. But on an abstract and argumentative basis, through most of his career, he was advocating for the supremacy of the individual.

Illustration of Emerson’s “transparent eyeball” by Christopher Pearse Cranch, c. 1837–1839 (Harvard University / Public Domain)

His kicking over of the confinements of organized Christianity is part of the same impulse. He came from seven generations of ministers, and after about three years as minister of the Second Church in Boston—a very prestigious Unitarian pulpit—he couldn’t stand it anymore. He was already feeling that Christianity as practiced was dead. It was a calcified institution with calcified rites and a calcified understanding of the world. So he left.

His thought was not always anti-Christian in a virulent way, but it was no longer Christian. He had strenuously argued that God was not out there as a sort of celestial supervisory presence, that God was in the individual human being. A great power had been relocated into the interior of every human soul.

LOA: There’s obviously a long thread in American self-conception about individualism, as well as the feeling of reinvention, looking for the new, throwing off old systems. What are your thoughts on Emerson’s Americanness? Does he speak to something foundational in the nation’s identity?

JM: His Americanness is very deep. He was one of the first writers to really ponder the question of what it meant to be an American—specifically an American writer, but also how being an American represented a rupture with being a European. His stress on individualism we can trace partly to his upbringing and to his own neuroses, but there’s something historical and cultural about it, too. This gospel that you can make yourself up from scratch was for many people the allure of coming to America in the first place. You could escape a rigorously class-bound society and reinvent yourself in a way that wasn’t possible in England or France, the nearest points of reference for Emerson and his peers.

I just imagine him walking around late at night, all the lights are on, he’s in his boxers (if they were even invented then). There is a hilarious and very human way in which he doesn’t conform to his own principles about life.

When Emerson went to England in 1847 to lecture and collect material for what would become his book English Traits, he was struck by the sense that everything was finished. The landscape had been manicured and husbanded and used up, and all was locked into place except for the amazing juggernaut of the British economy. He felt that England, as glorious as it was, might be reaching a kind of imperial senescence—that it would soon be going downhill. Whereas in America, everything was newness and possibility.

Emerson was partly shaped by these perceptions, but then he expressed them so eloquently and for so long that his notion of Americanness seeped back into the culture. Some aspects of that thinking—the idea that the United States was essentially an empty playground of natural resources to be claimed by white settlers—were wrong and strike many readers as offensive today. But the mythological feeling is certainly still very common in America now.

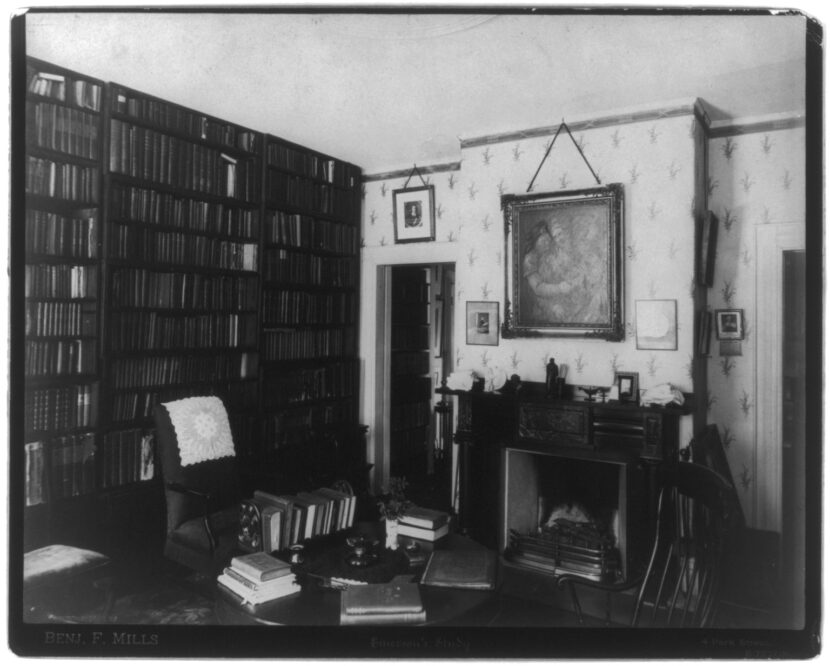

Photo of Emerson’s study in Concord, MA, c. 1888 (Library of Congress)

LOA: One of the great narratives of Emerson’s life is his evolving relationship to the question of slavery. Could you talk about this movement, which begins with him being more politically aloof or even disdainful of some of the more radical figures he encountered, and ends with him speaking so powerfully against the evils of slavery?

JM: Emerson’s record on slavery and abolition is fascinating and contradictory. In the early 1830s, abolitionism was still a fringe belief, and Emerson was aligned with many of his contemporaries in feeling that slavery was wrong, but not having any idea how to get rid of it.

By 1844, though, he had really pivoted. A key moment was a speech he delivered that year at a tenth anniversary celebration of emancipation in the British West Indies. For the first time he read deeply in the literature of abolition, particularly British literature of abolition, and it finally connected. He delivered a fantastic, detailed, scorching denunciation of slavery. From there until the dawn of the Civil War, he had an increasing commitment to the cause. He gave a series of speeches, many of them very strong. He raised money, after the war broke out, for the Massachusetts 54th, among the first federal all-Black regiments.

He never became a full-time activist. Just temperamentally, the mosh pit of politics was not designed for him. But he recognized that a great communal effort would be required to solve the problem of slavery.

There’s a beautiful moment, toward the end of the Civil War, where he says that the emblem of the United States should be not the bald eagle holding its quiver of antagonistic arrows. It should be, he said, “the Negro soldier lying in the trenches by the Potomac with his spelling book in one hand and his musket in the other.” He was essentially saying: That is the best of America, that should represent us to the world. It’s also very Emersonian to note the dual emancipation going on: one was the literal breaking of the chains with the musket, the other was learning to read and having your consciousness liberated.

LOA: Could you talk about Emerson’s friendships—or maybe frenemy-ships—with Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Fuller? Who were his peers and how did they influence each other?

JM: Emerson was a withdrawn, sometimes very socially awkward person. He himself once adverted to what he called “the porcupine impossibility of contact” with other human beings. Of course, there’s a wonderful consistency in feeling that way and then arguing that solitude is the purest condition of human life. If you don’t play well with others, that’s maybe a natural conclusion.

But Emerson was embedded in the social world of Concord, where he moved in 1836 after his marriage to Lydia Jackson, and he lived there until he died in 1882. Robert Gross wrote a wonderful book, The Transcendentalists and Their World, where he made that argument with an almost forensic reconstruction of life in Concord at that time.

Friendship was a fraught thing for him. He wrote an entire essay about it, which conveyed both his exalted feelings about it and also his fear that it would always disappoint him. He set the bar very high for transcendental friendship, almost guaranteeing it would fail.

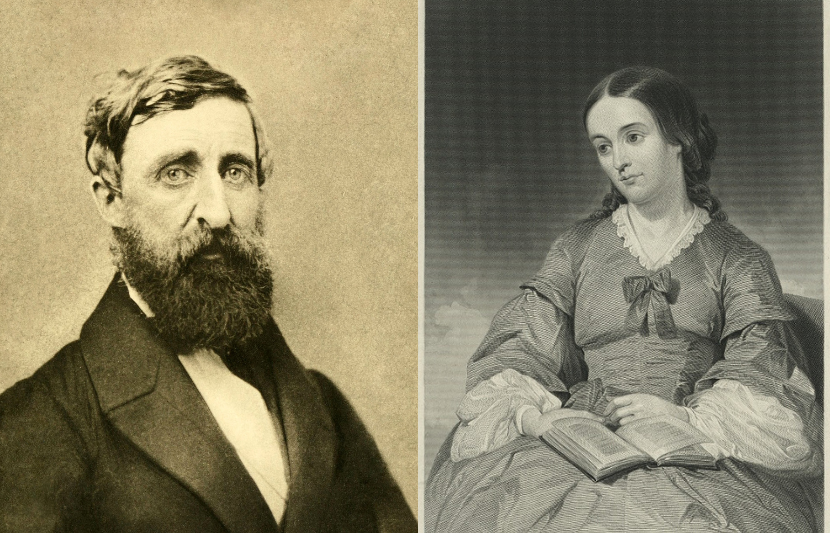

Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Fuller (Public Domain)

And yet you did have these people, like Margaret Fuller and Henry David Thoreau, with whom he had very intense and convoluted friendships, more akin to romances than regular friendships. There was an enormous power of attachment, an enormous capacity to hurt each other. That’s not a person who’s a hermit. That’s a person whose life was immensely enriched and complicated by other people.

There’s a funny note in the journals. It’s a February day and Emerson’s family has gone away for the weekend. He’s spent the past few years preaching the infinitude of private man, trying to escape into nature. And yet he writes, “Solitude is fearsome and heavy-hearted. I have never known a man who had so much good accumulated upon him as I have. Reason, health, wife, child, friends, competence, reputation, the power to inspire and the power to please. Yet leave me alone a few days and I creep about as if in expectation of a calamity.”

He’s literally falling apart with no one in the house. I just imagine him walking around late at night, all the lights are on, he’s in his boxers (if they were even invented then). There is a hilarious and very human way in which he doesn’t conform to his own principles about life, and friendship is very much an example of that. He was a social creature despite preaching the opposite much of the time.

LOA: You refer to Emerson’s journals as “an open pit mine,” where his rhetorical concepts were deposited and refined over time. What emerges in the journals that you don’t get from the published works?

JM: The journals are a literary monument of American culture. If Emerson had never published a word in his lifetime, and then some archivist unearthed his journals and published them in 1950, he would still be one of the greatest American writers of the nineteenth century.

I just read a book by Lawrence Rosenwald called Emerson and the Art of the Diary, which makes that very argument: the journal was the literary form that Emerson discovered for himself and where he really did his work. For Rosenwald, the published essays and lectures are derivative products of the journals. When you read an edition of the journals like the Harvard one, which is very copiously annotated, you’re constantly coming across notes at the bottom of the page saying, “a vertical pencil line drawn through this paragraph.” And then you’ll find the paragraph in “Nature” or “Self-Reliance.” Emerson was constantly shunting material out of the journals into his published work.

It wasn’t necessarily a one-way process. He would recopy bits from a lecture back into a later version of the journal to redo them, or draw repeatedly on one part of the journal and parcel it out into different things. You have this real-time logging of his thoughts, with the ever-present option to go backward or forward and reuse or revisit any of it.

Not everyone is going to buy these sixteen volumes of the journal, but there are wonderful selections. The two Library of America volumes, edited by Rosenwald, are great. There is a vivacity to them and a sense of Emerson’s personality that has been pruned out of the essays. There are boring moments, but sometimes a terribly quotidian thing becomes really interesting. You see him acting out what he said in “Circles” about the importance of taking yourself by surprise: “The one thing which we seek with insatiable desire is to forget ourselves, to be surprised out of our propriety, to lose our sempiternal memory and do something without knowing how or why.”

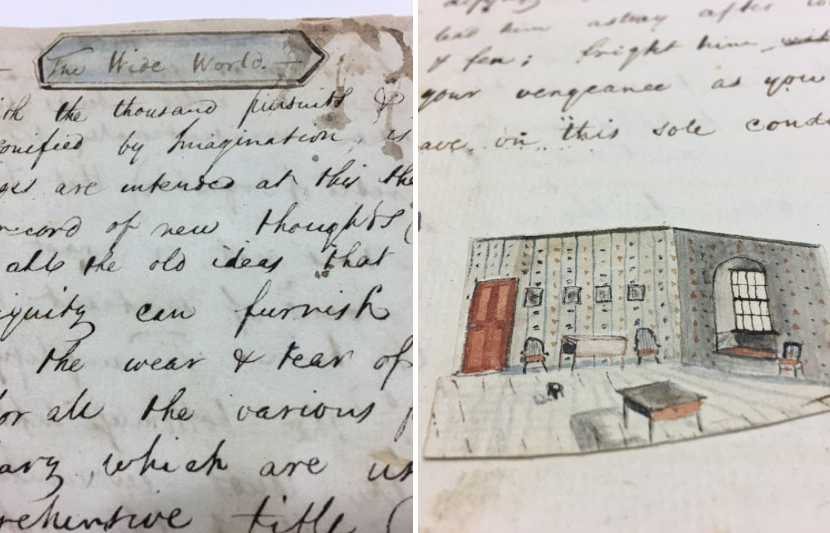

Excerpts from Emerson’s journals (Harvard University)

LOA: I’m glad you mentioned surprise. In all your reading of Emerson, can you think of a detail of his life or an aspect of his writing that surprised you most? Something that made you say, “That’s not who I thought Emerson was.”

JM: Discovering his method of composition was revolutionary. He not only created this monument of a journal, decade after decade, but he rigorously indexed it. There were hundreds of pages of indexing, and what that meant was when it was time to write, say, an essay on friendship, he could go to the index, look up friendship, and find all the sentences he’d ever written about it, coded according to which notebook they were in. Then he would take them all out and splice them together.

Once I realized that, it was incredibly liberating. I was familiar with the sensation in the essays of being bogged down by bumper-to-bumper sentences, and suddenly I thought, “Well, that’s what they are.” The thing to do, then, was just keep moving until another electrifying sentence lit up your brain. Emerson licenses you to take away what you want, to make a mini-anthology out of his anthology.

Reading about his two marriages was also terribly humanizing. Marriage number one was to Ellen Tucker, who was sixteen when Emerson met her, seventeen when they got engaged, eighteen when they got married, and nineteen when she died of tuberculosis. The imminence of her death hung over their entire marriage. Emerson was eight years older, but he was utterly infatuated with her, and her death was a catastrophe for him. He felt that he would not marry again. He said, “There is one baptism, one birth, one first love.”

And yet a few years later he married Lydia Jackson, who was a little older than him, a person of enormous theological and literary and spiritual curiosity. That was a very different sort of marriage. It wasn’t the doomed, infatuated first-timer. Instead you had a person who was very much Emerson’s equal, and who had to deal with the very bitter pill of discovering, a few years into their marriage, that her husband was not really a Christian. They both had been practicing a sort of eclectic, do-it-yourself form of Christianity, but the difference was that Emerson was trending away from it altogether, whereas Lidian, as he called her, was still a traditional Christian. That overshadowed their life.

Daguerreotype of Lidian Jackson Emerson and son Edward Waldo Emerson, c. 1850 (Public Domain)

Being married to Emerson was not always easy, I’m sure. Yet they stayed married for forty-six years, and when you read their letters, you see—along with some of the impatience and intolerance that will grow out of a long marriage—a lot of affection and mutual understanding.

Finally, I was surprised to learn more about the dementia, quite possibly the Alzheimer’s, that enveloped the last decade of Emerson’s life. This wasn’t hidden by other biographies, but sometimes they skated over it. He was one of the first really famous people to be observed retreating into the mists of this kind of dementia. He continued to lecture when he could no longer write, reading from pages that his daughter Ellen sewed together so that if he dropped them, they wouldn’t be scattered and impossible for him to reassemble.

Emerson was aware he was losing his memory, and like any dementia patient in the earlier phases, he would come up with workarounds. He called his dressing gown “the red chandelier.” He called the umbrella “the thing that is always taken away.” Seeing someone who was a worshipper of language his entire life struggle with this subtraction of language is very touching to me.

LOA: For those who come to Emerson for the first time through your book, or who haven’t read him since school, where would you recommend they start with his work?

JM: A great place to start is with his essay “The Transcendentalist,” which is not as celebrated as some of the others but is a rare instance of Emerson actually trying to explain something with maximum clarity. He’s not simply letting the Over-soul descend into him and speak. For that reason, it’s a really fun read. He gets down to the nub of it, but it’s also quite humorous.

Any of the anthologies or selections of his journals are a great place to start as well. I’m not suggesting people pick them up and read them front to back. Just flip around. They’re a browser’s delight because they’re so full of the spectacle of Emerson surprising himself.

For the stouter hearts who’d like to march into the more challenging essays, “Circles” is a very beautiful one, and it’s not impenetrable. It has a central idea that the circle is the great organizing metaphor of human life, and he lays it out in some very beautiful language. “Self-Reliance” is a key text for Emerson, but also for America and American culture, and I think it’s pretty damn readable.

But for me, his greatest single essay might be “Experience,” the one he wrote in the wake of his son’s death. It is shot through with terrible grief and a kind of sleepy, hallucinatory, depressed feeling. The topic makes him wrestle with some philosophical dilemmas, but a lot of it is about grief and survivor’s guilt. There’s a very complicated set of metaphors operating there, and it’s a very dense piece of writing. You just have to stay with it.

The philosopher and Emersonian Stanley Cavell said that in an Emerson essay, every sentence can be the topic sentence. I know exactly what he means: the sense that the center is everywhere and nowhere. “Experience” makes you feel like the thought and feeling and spiritual investigation of a four-hundred-page book has been compressed like coal into diamonds.

Based on my own experience, I would advise people to learn a little about Emerson, too. Sometimes this orphic voice issuing out of the skies can be very beautiful and exhilarating, but it seems unanchored to a human being. To know that he was a living, breathing, suffering, laughing person puts flesh on the bones of his sentences.

The home of Ralph Waldo Emerson in Concord, MA, c. 1883 (Library of Congress)

James Marcus is an editor, translator, and critic who has written and lectured widely on Emerson. His essays and criticism have appeared in leading publications such as The New Yorker, the Times Literary Supplement, and Harper’s Magazine. He is the author of Amazonia: Five Years at the Epicenter of the Dot.com Juggernaut.