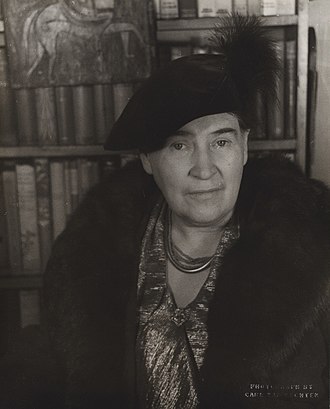

Portrait of Willa Cather (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution) and Willa Cather Memorial Prairie in Webster County, Nebraska (Public Domain)

What does it mean to mark a major anniversary—a 150th birthday, in this case—for a writer so gloriously out of time as Willa Cather? Born on a Virginia farm on December 7, 1873, Cather relocated with her family to Red Cloud, Nebraska, when she was nine years old, setting in motion the contradiction that would animate her artistic life: on the one hand, an unstoppable drive to escape her provincial origins and enter the literary pantheon; on the other, a preternatural attachment and sensitivity to the landscape and genius loci of her childhood.

Chasing Bright Medusas: A Life of Willa Cather by Benjamin Taylor (Viking, 2023)

In his engrossing and limpid new biography, Chasing Bright Medusas: A Life of Willa Cather (Viking, 2023), acclaimed writer Benjamin Taylor paints a portrait of an author whose moral clarity, personal idiosyncrasy, and incandescent prose has continued to win fans long after her death in 1947, when, dismissed as a “minor regionalist,” her oeuvre’s immortality was far from certain. But the tenacity Cather showed in her own career, both in her prodigious output and the lodestar of self-confidence that shines through her correspondence, met its complement in a readership keenly responsive to her stunning evocations of place and people, her ethical seriousness and sensitivity to lived experience.

“She never lost sight of the particular in the panorama,” wrote Eudora Welty. “Her eye was on the human being. In her continuous, acutely conscious and responsible act of bringing human value into focus, it was her accomplishment to bring our gaze from that wide horizon, across the stretches of both space and time, to the intimacy and immediacy of the lives of a handful of human beings.”

In a recent conversation with Library of America, Taylor discussed Cather’s long road to canonization, her complex relationship to gender and sexuality, and her surprising lack of “the usual occupational hazards” we tend to associate with authors of her stature.

LOA: Could you share the inspiration for writing this new biography? What made Cather compelling to you as a subject?

Benjamin Taylor: It goes all the way back to sixth grade for me, when my teacher, Mrs. Westbrook, recommended My Ántonia. She said, “This is a book I usually recommend to the girls, but it’s as much about a boy as about a girl, so I think you should read it.” Willa Cather was for me what Hemingway or Fitzgerald or Faulkner have been for other writers: the criterion.

LOA: You get the sense, reading your biography, that Cather is a figure out of time. She wasn’t aligned to modernism or the main literary currents of her moment, and instead carved out her own voice and identity. Could you talk about the historical context that she emerges from?

BT: She was disparaged by some critics as a minor regionalist, but in fact she always had her eye on the larger prize of being a universal truth-teller. And she is indeed what I would call an antimodernist: modernism meant nothing to her. Although she lived in Greenwich Village, the world of modernist experimentation was not her Village, nor was she drawn to leftist politics.

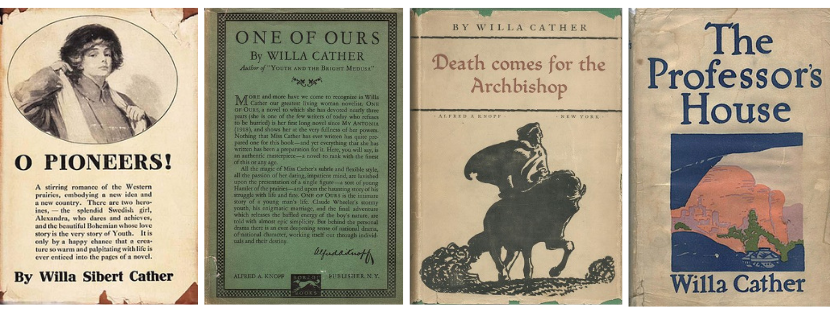

First-edition covers of O Pioneers! (Houghton Mifflin, 1913), One of Ours (Alfred A. Knopf, 1922), Death Comes for the Archbishop (Alfred A. Knopf, 1927), and The Professor’s House (Alfred A. Knopf, 1925)

Another thing I discovered was that she wasn’t at all a feminist, in the sense of being interested in votes for women. The great moral cause of her time, she was cold to. I don’t think she ever voted after the Nineteenth Amendment would have allowed her to. There’s nothing in her letters or anywhere else about feminism. She was a figure out of phase with her times.

LOA: What does that mean for us approaching her work now, when there is such an emphasis on writers’ political commitments and how they comment on or critique society? How would you recommend contemporary readers tune their brains to be receptive to what Cather is doing, even if it might be out of step with their preconceptions?

BT: She was certainly no provincial. She began provincially, as most writers of fiction do, and retained an attachment to the particular. All the particulars of her early experience are what register in those first great novels, O Pioneers! and Song of the Lark, and the emergence from a background of provincialism is a very familiar theme everywhere in her work. She was aware of having started in a remote, unimportant place—Red Cloud, Nebraska—but she had nonetheless a wisdom and a wish to be ranked with the great cosmopolitans like Henry James. I don’t know if Edith Wharton ever meant much to her, but among American women writers in the twentieth century, I think Wharton and Cather are the most important and most lasting.

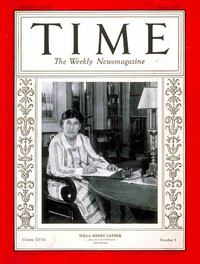

Willa Cather on the cover of TIME, Aug. 3, 1931

LOA: Despite the provincialism of Cather’s origins, from a very young age she had vast ambitions for herself. She saw herself as an artist, somebody who was destined for greater things. What could have produced this thinking in a child, in a woman, at that time?

BT: I’m struck by how often the great writer is someone who has done everything possible to get out of the place of origin and then obsessively writes about the place of origin once he or she is out of it—whether the place is Newark, New Jersey, or Dublin, Ireland, or Red Cloud, Nebraska. And Cather, like Joyce, like Roth, like Bellow with his Chicago obsession, could not stop the operations of her imagination on her origins. Even at the end, she’s writing novels that take place very provincially.

But isn’t this characteristic of fiction writing in general? To find some little milieu and compel it to stand for the whole of human nature, human possibility? That’s what differentiates a great novelist from a great philosopher; novelists delve so deeply into the particular that it touches the universal, rather than going directly to the universal, which is what philosophers strive to do.

LOA: What you say is so interesting when you consider that, at least in the popular imagination, Cather is often associated with an evocation of landscape. But the landscape is always operating psychologically or emotionally in her work; it’s never purely material. There is almost this metaphysical or spiritual component to it.

BT: She had the good fortune to be completely at home with the religion in which she was raised, Christianity. And I think that she always felt she was in a sacramental mode when she described nature. She describes nature in an extremely exalted way, particularly the landscape of the American Southwest. She actually felt sorry for people who didn’t believe in God, the creator of all this beauty; she felt that they were crackpots on the order of vegetarians or communists or other people she disparaged. That’s how she felt about atheists, too.

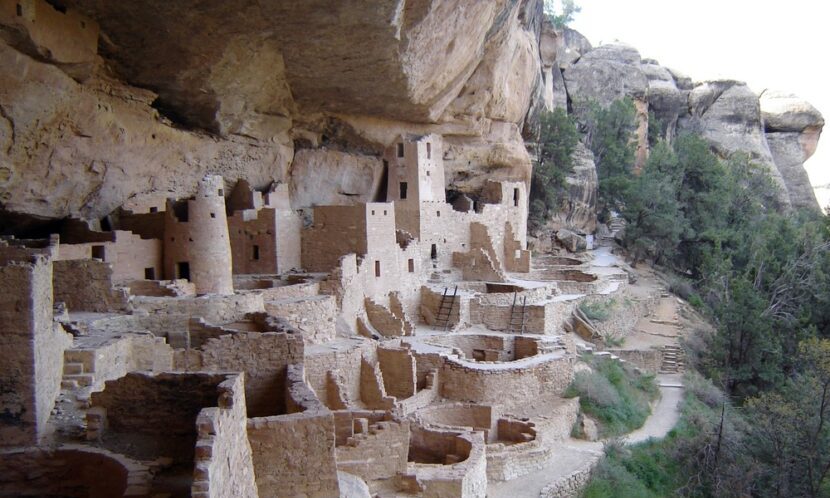

Cliff Palace, the largest cliff dwelling at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, a site of special importance to Cather (National Park Service)

She is obsessed with the idea of these nineteenth-century Spanish priests in the New World delivering the church from the decadence it had fallen into, and that gives her the subject matter of Death Comes for the Archbishop, a book that caused nearly everyone to assume that she’d become a Catholic. She never became a Catholic. She did go from being a Baptist to being Episcopalian. But she wrote for and was reviewed in Commonweal, and felt very at home with Catholic piety. If you look at that book, Death Comes for the Archbishop, you see that you’re in the presence of two men who are as attached as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. And they are the greatest of friends, even though so often distant from each other. No element of eros between them, no eros at all. So that gives you the formula for the book: two men who love each other, both of whom are probable saints.

LOA: That arrangement you just described, of celibate relationships, has an echo in Cather’s own partnerships with women. There are hints of her sexuality or sense of gender that appear in the work, but at the same time, in the biography, you take care to not draw one-to-one parallels between how Cather would have conceived of her identity and terms like queerness or homosexuality that we might use to describe it today.

BT: Today we would call her homosexual. She would have been astounded to hear that. It simply didn’t occur to her that that’s what she was. I think she probably thought of lesbianism as some sexual exoticism. She saw herself as exceptional rather than homosexual.

But she was very negative on sexuality altogether. Sexual need is the prelude to very bad things in her books, over and over again—you see this in Lucy Gayheart, for example, and the great story “Coming, Aphrodite!”

I think there was maybe a little bit of sexual activity with Isabelle McClung and maybe a little bit more with Edith Lewis, the two great loves of her life. But sex certainly wasn’t the tie that bound her to anyone. I just don’t think that that aspect of life figured much to her, and she dreaded it. But she didn’t dread it in her writing; the wages of sexual need were very often the engine of her writing.

Isabelle McClung, an unidentified man, and Willa Cather in 1902 (Philip L. and Helen Cather Southwick Collection, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries) and Edith Lewis with Cather in New Hampshire, 1926 (Special Collections, University of New Brunswick)

It was something entirely personal, not an outgrowth of her Christian principles. She had male friends. She even had suitors in college. She carefully arranged to avoid the path to betrothal and marriage. There was one young man, very fond of her, who gave her a serpent ring. It was a ring she wore all her life, as if to remind herself of the road not taken: heterosexuality.

LOA: Can you talk about the evolution of Cather’s style over the course of her career? She was a critic of many contemporary strains in the novel, specifically the idea that they had become, as she called it, over-furnished, overstuffed with material detail. Her project seems distinct from that. How did she separate herself from her artistic peers?

BT: She writes a couple of bulky novels before she renounces this overstuffed tradition. She writes The Song of the Lark, her longest book, and One of Ours, which is also rather long. And that’s the moment when she wins the Pulitzer, and also the moment when she fastens on the idea of a simpler style. You can see the dramatic stylistic difference between, first, One of Ours, and then, immediately after it, A Lost Lady, which is the pivotal work and a marvelous book. But that is the novel démeublé, as she calls it, “the unfurnished novel.” It’s as if, in middle age or a little past middle age, she discovers a style of old age for herself that she will not veer from.

I would recommend people just getting to know Cather to start with those great works of the ’20s that are in the démeublé mode: A Lost Lady, My Mortal Enemy, The Professor’s House, and Death Comes for the Archbishop. In those, you have Cather at her greatest. I’m in love with the whole career, but there’s really nothing to compare, for example, to that middle section of The Professor’s House called “Tom Outland’s Story.” Eudora Welty said that was the best thing she ever wrote. Welty, Katherine Anne Porter, and Alice Munro are all great readers of Cather. But when I looked at slightly younger women writers who came to prominence in the ’50s, I didn’t find one mention of Cather in Mary McCarthy’s or Elizabeth Hardwick’s writings. Her reputation was at a low ebb in the ’50s; it was second-wave feminism that brought Cather back.

Cather in 1936

(Carl Van Vechten

/ Library of Congress)

She never publishes another book after 1940. She had tendinitis in her right hand that impeded her, and she found she could not dictate fiction, only letters. So in the last seven years of her life, she didn’t write very much of anything, and she was in the process of being forgotten or relegated to the status of minor regionalist. But along about the mid-1960s or thereafter, really with the arrival of feminist scholarship, people began having another look at her, and then her reputation began to rise and went on rising. I think now she’s found her place as a permanent adornment of American writing.

LOA: One book you make a case for in the biography that is, I think, not frequently considered among Cather’s best is One of Ours, her war novel. Can you talk about that book and how the negative reception it received from many critics affected her?

BT: It got some good reviews, but it didn’t get the reviews from the quarters that mattered to her most. Mencken didn’t like it and others denounced it because their idea of a war novel would be one that was more in a Dos Passos mode, showing the futility, the absurdity of the Great Conflagration, which her book does not. She was accused of being a sentimentalist about the war. I don’t see it that way. Hemingway wrote a letter to Edmund Wilson—maybe a drunken letter—saying, “What did you think about Willa Cather’s book? How about those battle scenes? I know where she got them: The Birth of a Nation. Well, the poor woman had to get her war experience from somewhere.”

Cather didn’t go to the movies. She would not have seen The Birth of a Nation, and I think this is an unfair depiction of the war scenes. I wish that the world would give that book another look.

At the time it was published, the most admired American book about the Great War was Dos Passos’s Two Soldiers and also E. E. Cummings’s The Enormous Room. Her book was in a very different mode. She felt that the pacifists had done her wrong in their response to the book.

Cather at Mesa Verde, 1915 (Public Domain)

LOA: Cather produced a remarkable quantity of writing in her life, first as a prolific journalist and essayist, and then there are the stories and the correspondence. Can you talk about the body of Cather’s writing outside of the novels?

BT: She wanted none of that early journalism ever to be reprinted and didn’t want to speak about it. But it’s a very long foreground to her career as a fiction writer, in which she writes first for the Nebraska State Journal, the major newspaper of Nebraska, and then goes on to edit a women’s magazine in Pittsburgh. Next, she gets the call to come to New York from S. S. McClure, and she writes for and edits for McClure’s Magazine—that’s her big break. She’s pioneering her way eastward from Red Cloud to Lincoln, from Lincoln to Pittsburgh, from Pittsburgh to New York. And journalism is how she does it.

LOA: When you look at Cather’s letters, are there things that jump out to you that someone who only encounters her through her fiction might miss about her as a person or a friend?

BT: She had none of the usual occupational hazards: no alcoholism, no mental illness. There may have been a kind of depression after One of Ours, interestingly, because though it was a great commercial success and won the Pulitzer Prize, the critics that mattered to Cather didn’t get behind it, as I say. But then I think she emerged from that, that one depression that I can identify in her life in the early 1920s, and wrote A Lost Lady.

Another was just how untragic it was. The first death that touched her deeply was that of her father, when she was in her fifties. That’s awfully late in life to have a first crushing loss to death. But that was her life. It was extremely orderly and uncrazy. And I went into it thinking, well, I’m sure she had a Bourbon each evening. But no, not even that.

Willa Cather’s childhood home in Red Cloud, Nebraska (Public Domain)

Benjamin Taylor (Alison West)

Benjamin Taylor is the author of numerous books, including the memoirs Here We Are and The Hue and Cry at Our House, the biography Proust: A Search, and two novels, Tales Out of School and The Book of Getting Even. He received a 2021 Literature Award of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, is a past fellow and current trustee of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and serves as president of the Edward F. Albee Foundation.