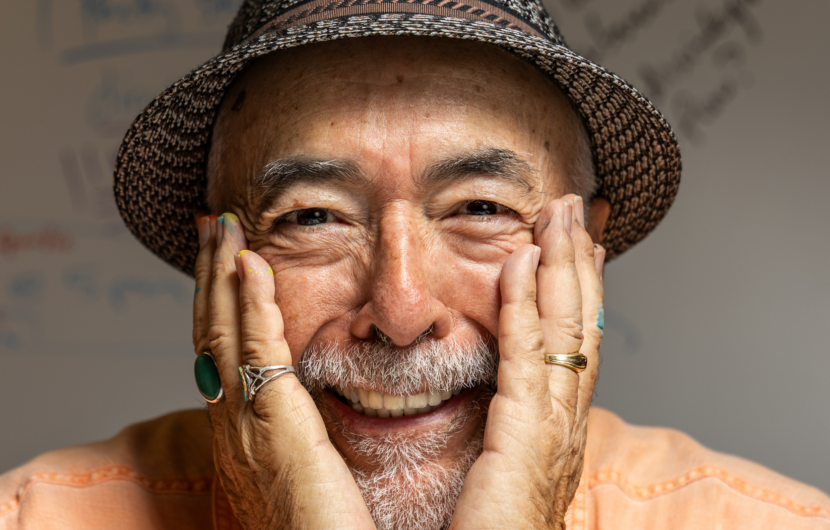

Juan Felipe Herrera in 2024 (John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation / CC BY 4.0)

Juan Felipe Herrera, twenty-first Poet Laureate of the United States and a 2024 MacArthur “genius grant” recipient, sat down with Library of America to read and discuss poems from Latino Poetry: The Library of America Anthology. He spoke about the longstanding political and spiritual underpinnings of Chicano poetics, the continuously reverberating meanings of “exile,” his surrealist-inspired approach to language, and his lifelong friendship with fellow poet Francisco X. Alarcón, who died in 2016.

Below you’ll find recordings and comments on three poems: Herrera’s own “Exiles” and “The Women Tell Their Stories,” and Alarcón’s “In Xochitl In Cuicatl.” The following remarks have been edited and condensed for clarity.

“Exiles”

The title of the book this poem comes from, Exiles of Desire, stems from a very important moment for me as a writer. I was in the Bay Area, in San Francisco; I wrote day and night, every minute. I was almost too deep into poetry, but that’s the way it was.

Writing this poem was a different approach for me. Usually, I would write in a conversational style, where the lines kept on going until the story was told or the moment was fulfilled. But this poem, perhaps, is like a bridge unto itself. I just let it take its own momentum and let that bridge roll out and float on.

And yet this poem is also a painting, inspired by the expressionist Edvard Munch. The poem is calling out, and that scream is a scream of names of people that are made invisible, or are missing or dead, or that are coming back to life or being called to life.

Chicano Movement protests and demonstrations. Clockwise from top left: Members of MEChA calling for free college tuition (CC BY-SA 3.0), boy with ‘Viva la Revolución’ sign in 1968 (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center / Pedro Arias), and La Marcha por la Justicia in 1971 (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center / Luis C. Garza)

It also represents a sharp shift away from the early ’70s, when I was more focused on Mesoamerica as a cultural source, not as a source of revolution. In the early ’70s, when the Chicano literary movement was beginning to gain momentum, the key themes of that movement came from Indigenous sources and peoples, in particular the Aztecs and the Mayas.

But when I was writing this poem, things had changed. The notion of “exiles of desire” in general relates to a new atmosphere or phenomenon that I was tapping into, and that I think most of us were tapping into after what took place in Central America and in El Salvador, in Chile—the war and the violence and the role of the United States. All of that created a sensibility of being exiles in the United States, even for those of us who were citizens. Regardless, we were attempting to reach a place to call home. And looking at all of that, I sensed we were exiles of some fashion, exiles of desire.

There were protests and a lot of turmoil. We did not want the United States participating in those wars. We did not want to contribute military assistance in those wars. People were suffering enough.

And the words ‘ethylene’ and ‘propylene,’ those are good words, with a lot of shoeshine. And ‘Kabul’ and ‘Kashmir’ and ‘Fallujah’—those are great sounds, but also realities. All those words are, strangely enough, delicacies.

Today we’re still dealing with the same questions. In terms of Central America and Mexico and the United States, we have the terrible experience of migrants being stopped at what is called “the border” in a very brutal manner, through razor wire, helicopters, horses, jeeps, and weapons—of being pushed back without their children and without their parents and then dying in a cell on the border line in the hands of ICE.

So the terror, the scream, is still audible, and it reaches us all across the United States and beyond. Everyone knows what’s happening and how our migrants are suffering, and our migrant children are suffering, and how we’re being thrown into buses going nowhere, and deported here and re-deported there.

The bridge is still there and people are still attempting to cross that bridge, and I don’t blame our peoples. That’s what we do. This land was once our land, and we have families here. Of course it was also Native land, which is part of our history as well. And that’s kind of a vacuum, an existential vacuum. There’s nowhere to go.

Watch: Juan Felipe Herrera reads in 1973

“The Women Tell Their Stories”

This poem comes out of several moments and sources, in particular the Gulf War in Iraq. It also situates itself in the United Nations, Kuwait, the United States, Kashmir, Fallujah, and Kabul. Of course, there were bombs, explosions, planes, and jets. All those things were swirling around in the early ’90s, and we were all in that current, that strong riptide. We were all watching it on TV. We were all engaged in it and affected by it.

During this time, I had been to Austin, Texas, to give a workshop for migrant women. I was there to assist them in getting their writing skills going and, ideally, creating a poetry collective. I was attempting to figure out how I was going to do that. I knew I wasn’t going to get up there and say, “I’m going to have a poetry workshop and first we’re going to look at language.” I wanted their stories to be first.

These were stories of different incredible moments in these women’s lives and their almost impossible journey. The workshop was very rich with what they said and how they said it, and how they wrote it was beautiful. They read everything out aloud at the culmination of the program, but in the end, it’s not all in here; it’s just the one line that stayed.

The rest of the poem moves in a different direction, toward a more lethal kind of conflict. Here I focus on the materials of war: the bombs, the planes, the propellant in those bombs. All those things were moving in my approach, in my initial self-combustion of getting onto a piece of paper the various ingredients of wars, and women crossing borders, and Afghanistan, and so on.

I picked out facts from the news: the 15,000-pound fuel-air explosives. I thought that was a good phrase and an important item. It’s good to put little facts in poems. And the words “ethylene” and “propylene,” those are good words, with a lot of shoeshine. And “Kabul” and “Kashmir” and “Fallujah”—those are great sounds, but also realities.

All those words are, strangely enough, delicacies. Not in their reality, their harsh, terrible, bloody reality, which we want in here. But unto themselves, as terms and words and sounds and music. All that is very important in a poem, but you’re not going to force it. If it’s something that you have in your hands already, you’re not going to shy away from it. “Oh, I can’t say that. It’s too plain.” Do not worry. Be plain and you’ll see what happens.

Juan Felipe Herrera (Carlos Puma for University of California, Riverside)

“In Xochitl in Cuicatl”

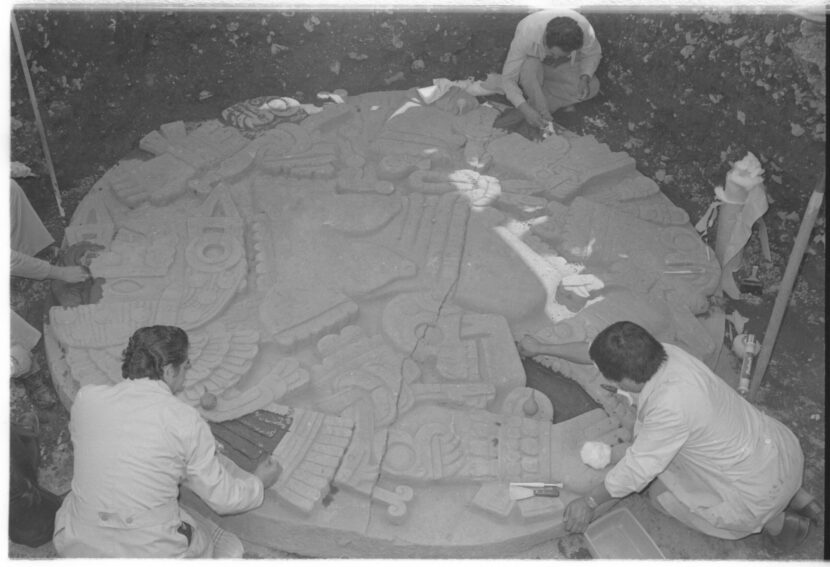

I’m so happy to read this poem, “In Xochitl in Cuicatl” by Francisco X. Alarcón, a dear, dear friend of mine. We met at Stanford at an orientation in 1977. We eventually traveled to Mexico together, where we met many writers and publishers and artists, and we were able to see some of the archeology that was being uncovered—those things we bumped into, literally bumped into, Francisco Alarcón and myself, strolling around the big city of millions with a lot of history in it, Mexico City.

Alarcón passed away in 2016. And to tell you the truth, I think that Francisco Alarcón … it’s hard to put into words, but he was just so great, not only his literary output—his sonnets, his poems of love—but his depth, his research, his intellectual expanse. I haven’t seen a deeper set of research materials for a book than for his Snake Poems, where this poem appears.

Also interesting is his global reach. He journeyed to Ireland, where he was like a brother to all brothers and sisters in Ireland. To have your poems translated into Gaelic, which he did, is quite a feat, especially for a gay Chicano poet. And it’s because he embraced the Irish as well, and their history.

At one point, in San Francisco’s Mission district, he demarcated a cube of four or more blocks, and at every corner he created a ceremonial pilgrimage around those blocks, a social cube. And in every corner, he recited poems in Nahuatl with a bowl of burning copal incense used in the ceremonies and celebrations of the Mexica peoples, way back in time and still to this day. He bowed to the four directions and would say, “Tialli. Tialli. Tialli. Tialli. Hello. Hello. Hello. Hello.” Then he would go on to the next corner, until he completed the cycle. People in large numbers began to follow him. It was an installation, but also a vision of a kind of society.

Archaeologists uncovering the Coyolxauhqui Stone in Mexico City, 1978 (CC0)

In the title of this poem, xochitl is flower and cuicatl is song. Flower and song together is poetry for the Aztecs. This comes up with another poet, Alberto Urista Heredia, who wrote a book in 1971 called Floricanto.

And then with the first poet of Mesoamerica, Nezahualcoyotl—Nezahualcoyotl being the hungry coyote, a prince of Texcoco, one of the provinces of central Mexico, in the 1400s. In his poetry, he says that flowers are short-lived. We’re like them; we have a short life, too. Life comes about, and then, before you know it, it has vanished. And we say, “So what?” Impermanence.

This is important, because it suggests that we must celebrate life. If life is so short and everything we see only lives for so long—which is true—then what do we do? Nezahualcoyotl said that we must celebrate. We must sing and we must be the singers. So that’s what envelops the title of this poem. This poem is to celebrate life and all the lives that only last so long, which is something that our first poet in Mesoamerica said and wrote.

This is a short poem and each line has two words. “Every tree.” Next line. “Un hermano.” Every tree. A brother. That’s a big statement in only four words, in two thin lines. That was always the power and ability of Francisco Alarcón.

One time, when we were on the way to the anthropology department at Stanford, Alarcón showed me some poems. They looked just like this. Maybe four lines. And I looked at him and he read them out loud. I go, “Geez, that’s easy.”

After all these many, many years, I really see the beauty and deep meaning in them, how profound they are. I see all these words filled with light, knowledge, and those things we used to call “messages” that poets are taught not to have in their poetry. It’s almost a sermon: unity, totality, sisterhood, brotherhood, all things in one.

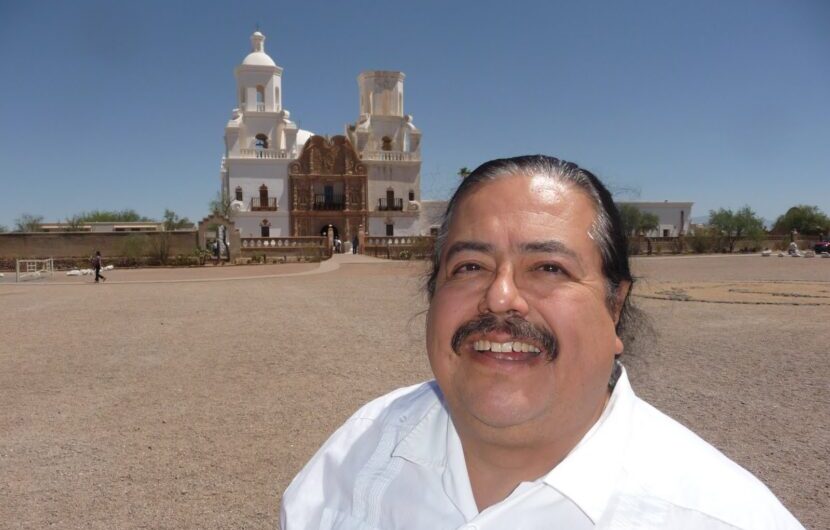

Francisco X. Alarcón (University of Arizona Press)

Fireflies are really tiny, aren’t they? And they only brighten up for so long. And Alarcón sees these as dreams: They’re dreaming up. We’re dreaming up. The poem is dreaming up the entire cosmos. The notion of dreaming up the entire universe—in a way, that’s what poets do. But usually we’re not that concerned with having that vision. We’re concerned with much smaller things.

Perhaps with Francisco Alarcón today, we can step back and begin to reflect on a much bigger life beyond our own experiences and moments. We can say that life is as big as the cosmos, and perhaps bigger. We can dream that up and we do dream it up.

Why was this meaningful to Francisco X. Alarcón? Because he was that man. I encourage you to read some Nahuatl and Alarcón’s work and explore those short lines. You don’t have to drive those big cars all the time. We can simply walk on the earth.

We are all those languages—Spanish, English, Nahuatl. Everything on this earth, we’re made out of it. It opens up our consciousness, we add a new set of streams, a new rhythm to our consciousness of humanity, that is real and that’s everywhere. Cada arbol un hermano. “Every tree a brother, a sister.” Definitely! Cada cuerpo. “Everybody.”

It’s going to be that. I’m headed in that direction. And I thank Francisco, and all of you.

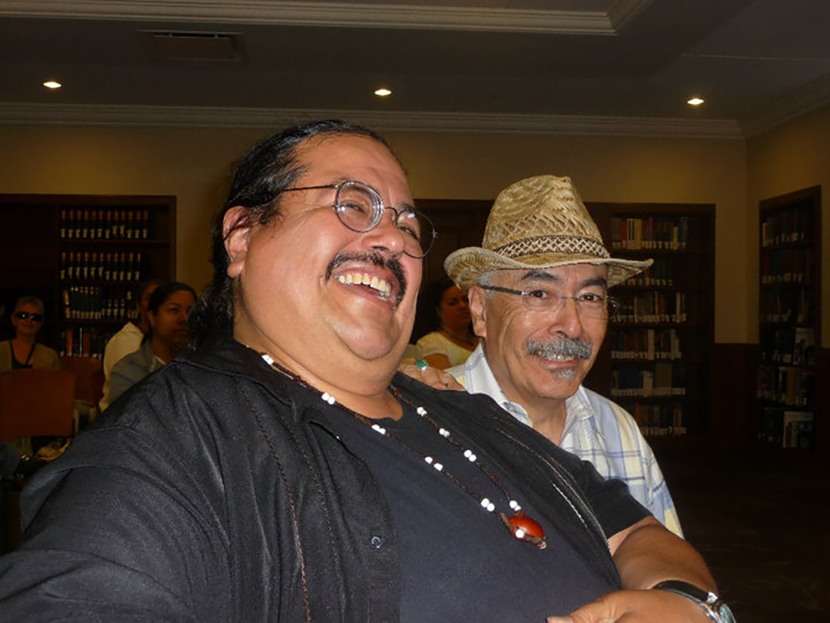

Francisco X. Alarcón and Juan Felipe Herrera (Letras Latinas)

Juan Felipe Herrera is the author of the novel-in-verse Crashboomlove (1999), which received the Americas Award; the poetry collections 187 Reasons Mexicans Can’t Cross the Border: Undocuments 1971–2007 (2007), Half of the World in Light: New and Selected Poems (2008), and Every Day We Get More Illegal (2020); and the children’s book Jabberwalking (2018), which won an International Latino Book Award. Has taught Chicano and Latin American studies and creative writing at California State University, Fresno, and University of California, Riverside. The recipient of a Latino Hall of Fame Award, he was California’s Poet Laureate from 2012–15 and U.S. Poet Laureate from 2015–17. He received a MacArthur Fellowship in 2024.