Portraits of John Quincy Adams in 1796, 1818, 1828, and 1843 (Public Domain)

A living link between the generation of the Founding Fathers, the advent of Jacksonian Democracy, and the rising tide of westward expansion and sectional conflict over slavery, John Quincy Adams was the rare American president whose single term in the nation’s highest office may not, in the final calculation, represent the apex of his political career. Rather, over his decades in the public eye, first as an ambassador, then senator, Secretary of State, Commander in Chief, and finally congressman for his home state of Massachusetts, Adams construed a political vision of the United States rooted in the Declaration of Independence and its commitment to liberty and equality among men.

In the recently published Library of America edition of Adams’s speeches and writings, historian David Waldstreicher gathers this consummate statesman’s greatest statements on democracy, abolition, and the role of federal government, illustrating his prescience, erudition, and acuity in response to competing visions of the nation, the fault lines of which remain visible to this day.

Below, Waldstreicher discusses his curation of the new volume, Adams’s ardent and complex nationalism, and what his words can teach us about dissent and popular representation in our own time.

LOA: This volume covers Adams’s half century in public service, from his Harvard commencement address in 1787 to his late-career antislavery writings. Can you discuss how you assembled the materials for this volume?

David Waldstreicher: I wanted to provide as much of Adams’ eloquence and acuity as possible, in different expository genres, and especially to show how he gradually came to face the problems that slavery posed for nationality, among other legacies of the American Revolution.

The biggest challenge was that Adams wrote so much, for so long. Like all editing, it was a balancing act to represent the many stages of his career while tracing important through lines in his thinking. My hope is that reading these works in context, and together, a whole emerges that is greater than the parts, great as they are. I also hope the volume will have some pleasant surprises for readers.

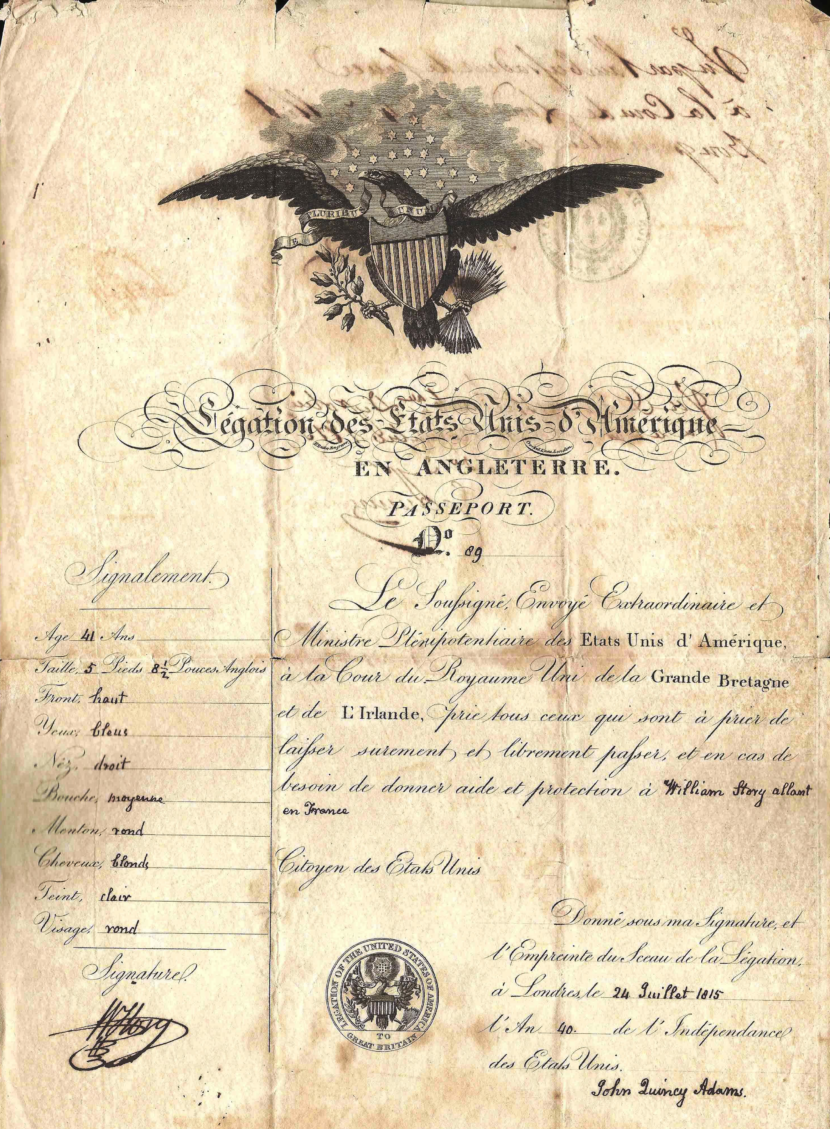

United States passport issued to John Quincy Adams in London, 1815 (Public Domain)

LOA: You previously edited LOA’s two-volume edition of Adams’s diaries, and in this new companion volume you provide helpful headnotes that draw out Adams’s private reflections. What emerges in the journals that might enhance our understanding of Adams’s published writings, and vice versa?

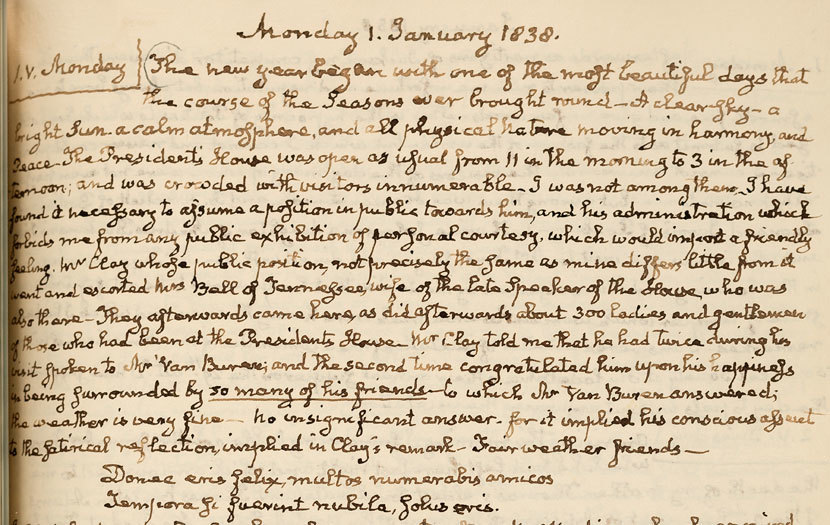

DW: As I was editing the diaries it became clear to me that Adams developed arguments there that he would present publicly, or codify, in major speeches. We also see in the diaries his reactions to major events, and to political opponents, that provided motives and contrasts and occasions for making tough choices—some more explicit than others.

It’s important to remember that he was a student of rhetoric, the first Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard. He always had a distinctive voice, but the diaries help us position his major efforts in time and place. They also show us how much work he put into these writings: he complained about it regularly in the diary! He was rarely satisfied, even though he knew he was often working under deadlines.

The emphasis on fighting can lead us to ignore how much Adams played by the rules. But because he knew the rules so well, he could push them to the edge.

Eventually, the fruits can be seen in the published versions of his Congressional speeches, where he was both using ideas and bon mots he had taken time to develop, and quickly editing them for newspapers and the Congressional Record, and sometimes for pamphlet publication.

Detail from the diary of John Quincy Adams (Massachusetts Historical Society Collections)

LOA: A through line in Adams’s thought is his belief in the union: the idea that the nation is not, in his words, “a mere cluster of sovereign confederated States,” but a single people united under a common national government. As sectional conflict mounted in the nineteenth century, how did Adams defend his vision of America?

DW: Adams was predisposed to think nationally because his political career began with national service, in the fledgling diplomatic corps. Spending time abroad focused him on the national interest and American distinctiveness; so did being the son of a leading revolutionary, vice president, and president.

He was of course a New Englander, but he was less tied to New England networks than virtually all of his contemporaries. Then, during the Jefferson administration, at a moment when sectional and partisan loyalties came to overlap and reinforce each other for many New Englanders, he cast his lot with the Jeffersonians and left the Federalist party.

His anti-partisanship, partially inherited, is often said to have doomed his presidency, but it was also a source of his appeal, and of his rise in the Madison and Monroe administrations. He balanced the Monroe cabinet and thought he could continue to play that role in Washington.

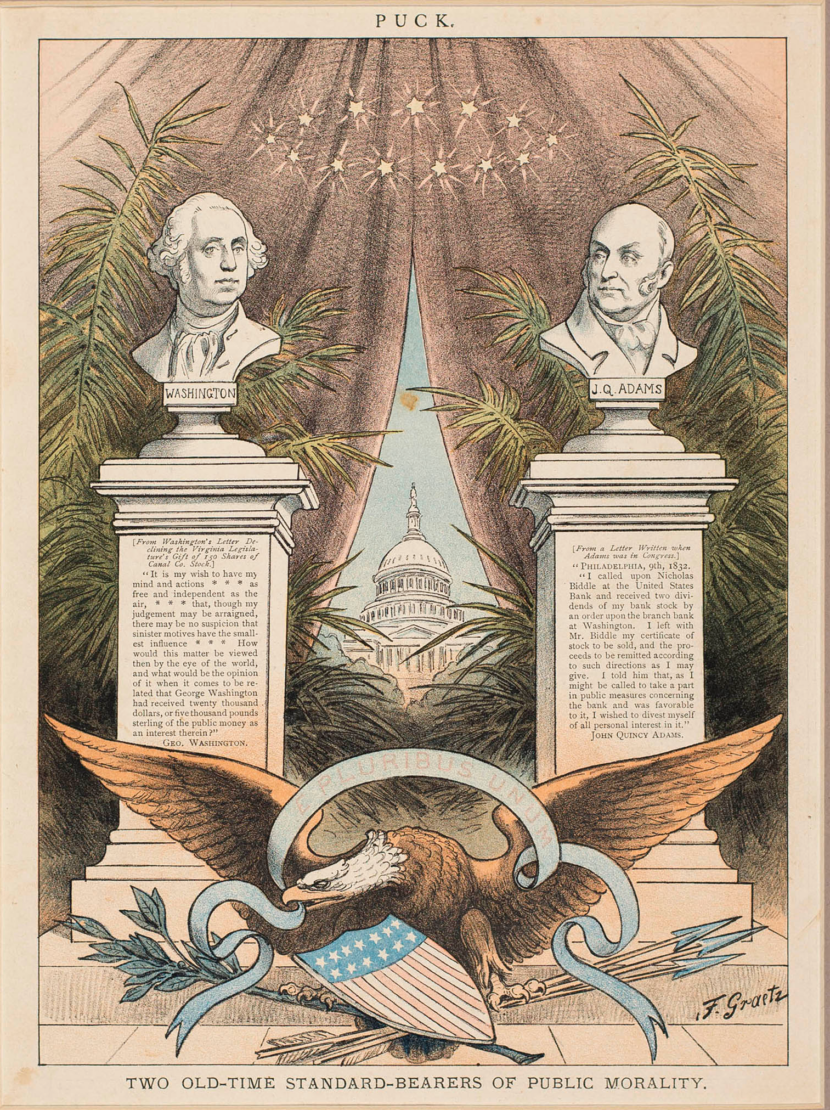

Two Old-Time Standard-Bearers of Public Morality chromolithograph by Friedrich Graetz depicting busts of George Washington and John Quincy Adams, 1884 (Massachusetts Historical Society)

His nationalism never abated, but he came to realize that he had provided cover for a southern-dominated, proslavery regime. One of the things that this edition of his writings brings out is not only his consistent nationalism, but his insistence that the nation was created in 1776, not 1787, and that the proslavery compromises could be revised by a return to the principles of 1776.

LOA: Among the more remarkable arcs in Adams’s long career is the evolution of his thinking on slavery, from studied avoidance for the sake of union to the late-in-life denunciations of the “slaveocracy” from the floor of Congress. What explains this change of heart about the slave system and the existential threat it posed to the nation?

DW: There were two factors that can’t be separated. First, his alliance with southerners, through which he thought national progress could be managed, fell apart during his presidency. Then he became convinced that the “slave power” actually threatened the liberatory fruits of the American Revolution. There were certainly intimations earlier (see the “Publius Valerius” essays of 1804), but being out of office, and the trends under Jackson and the Democrats, led him to a reconsider what he in particular ought to say.

After 1831, too, his job was different than it had ever been, even during his years in the Senate. Representing his constituents in eastern Massachusetts, who were increasingly antislavery, in Congress, freed him to dissent as well as to compromise and lead.

Watch: David Waldstreicher on the Diaries of John Quincy Adams

LOA: While the pieces in this volume can be read as a chronological narrative, they also stand alone as remarkable works of rhetoric and composition. Which speeches or writings provide an especially compelling distillation of Adams’s beliefs and literary style?

DW: While the Fourth of July addresses of 1793 and 1821 have long been noted and quoted as important and memorable versions of that genre, it’s the Congressional speeches where we begin to see Adams’s skill at calling out hypocrisies and making connections between political issues all too conveniently kept separate. The 1836 Speech on the Joint Resolution, where he predicts a proslavery foreign war leading to emancipation, is the epitome. It’s been neglected, even though it sets up his more famous Gag Rule speeches.

I do think that Adams’s early experience in thinking and acting internationally served him well in dissecting and representing the politics of slavery in opposition, during the 1830s and 1840s. We see this in his first anonymous essay series for newspapers during the 1790s, and it also helped him protect the National Republicans, from Jefferson to Monroe, from being accused of partial, proslavery policies.

LOA: Thanks to his fierce polemics against the Jackson administration, Adams gained a reputation as a principled and commanding voice of dissent (“He is no literary gentleman, but a bruiser, and loves the melee,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson). What can Adams teach us about opposition and resistance to political headwinds, especially today, in our own fractious moment?

DW: The emphasis on fighting in the famous and delightful Emerson quote can lead us to ignore how much Adams played by the rules. But because he knew the rules so well (e.g., the rules of the House of Representatives, the rhetorical expectations of his audiences) he could push them to the edge.

Abolitionists were sometimes frustrated with his disinclination to call himself one, but they appreciated that in his position, as a congressman and ex-president, he could do things that no one else could for the cause.

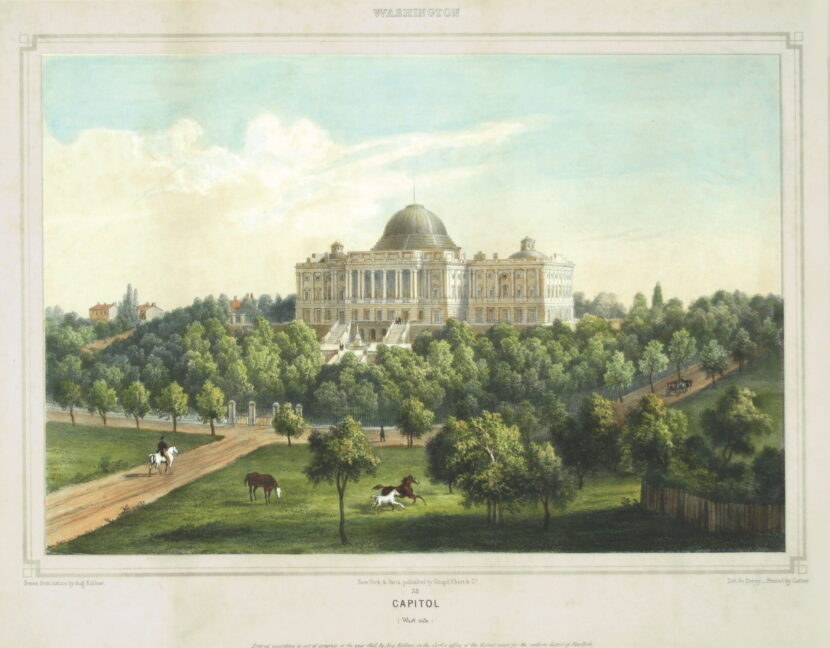

Colored lithograph of the U.S. Capitol in 1848 (Public Domain)

LOA: In the midst of a dedication speech for a newly built canal in 1828, Adams raised a shovel to symbolically break ground on the project—and promptly struck a buried tree stump. The resulting incident, in which Adams stripped off his coat and “went seriously to work” on the offending root, endeared him to his Washington audience but is notable as a rare moment of public spectacle in an otherwise highly restrained and stunt-averse career. What can we learn about Adams’s character from the “stump” incident, and how might it help explain his political fortunes?

DW: Louisa Catherine Adams once noted the disparity between her husband’s public image as august and aloof, and his Yankee earnestness and conversational skill in more intimate settings. The Jacksonians seized upon his intellectualism to cast him as “the professor” against their “ploughman,” suggesting that Adams was an elitist intellectual opposing their soldier of humble origins (who was actually a rich plantation owner). He loved to plant trees and work in his garden in Quincy, Massachusetts!

But I think Adams instinctively grabbed that shovel because he could sense an opportunity to demonstrate his belief in hard and common work, and in a vision of transportation improvements that would help ordinary people.

LOA: Unlike most presidents, Adams’s time in the nation’s highest office is not considered the summit of his political career. Hamstrung by determined opposition, he became, after his father, only the second president to be turned out after just one term. How did failure mold Adams?

DW: Political failure added a measure of humility and a longer-term perspective that he might not have otherwise achieved, and which many—perhaps most—politicians don’t have.

1843 daguerreotype of John Quincy Adams by Philip Haas (Public Domain)

David Waldstreicher is Distinguished Professor of History at the CUNY Graduate Center and the author of numerous acclaimed works, including The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley: A Poet’s Journey Through American Slavery and Independence, winner of the Francis Parkman Prize, and Slavery’s Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification. He is the editor of A Companion to John Adams and John Quincy Adams and, for Library of America, of The Diaries of John Quincy Adams in two volumes.