1904 portrait of Helen Keller (Public Domain) and Keller’s signature (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Few literary lives combine personal resilience, political vision, and deft artistry to the extent of Helen Keller. After an unknown illness in infancy left her without vision or hearing, she found herself, in her words, “at sea in a dense fog.” But under the tutelage of Anne Sullivan, her lifelong companion and teacher, Keller developed a deep and transcendent affinity for language that gave rise to an astonishing, hitherto unparalleled, writing career.

A new LOA edition, edited by leading disability studies scholar Kim E. Nielsen, bookends Keller’s revelatory autobiographies The Story of My Life (1903) and The World I Live In (1908) with selections from her essays, speeches, letters, and journals, many of them out of print or previously uncollected. The materials span more than half a century, offering unprecedented insight into Keller’s wide-ranging commitments to social and economic justice, pacifism, and antiracism.

In an interview with LOA, Nielsen introduces us to Keller in her multiplicity: the first deaf-blind college graduate in the United States, an activist-intellectual whose “genius for psychological insight” was praised by William James. Below, hear how Keller combated naysayers of her natural abilities, found solace sitting in trees, and weathered the vicissitudes of celebrity.

LOA: Many Americans know Helen Keller for her remarkable personal story as the first deaf-blind person in the United States to graduate from college. But she was also a prolific and talented writer who authored fourteen books and hundreds of shorter pieces, covering topics as diverse as socialism, religion, and her love of animals. How would you describe and contextualize Keller’s literary accomplishment?

First-edition cover of The Story of My Life (Doubleday, 1903)

Kim E. Nielsen: Keller’s literary career began with The Story of My Life and continued throughout her lifetime. Whatever she wrote, she positioned herself as a quintessential American who valued both independence and community, always embedding her literary works in the Western literary canon by quoting and referring to other works.

Despite resistance she faced for being a woman, and a deaf-blind disabled person, she claimed a space, literary identity, and voice for herself. She wrote of her ideals and passions, and did so to encourage others to share and learn from those passions. She is a U.S. literary figure of immense consequence who was and continues to be read widely across the globe.

LOA: Keller became a celebrity in childhood after the Perkins Institute for the Blind publicized the success of her education there (while downplaying the crucial role of her teacher Anne Sullivan, who would remain Keller’s lifelong companion). At the same time, Keller recalled some elements of the school as “hostile and menacing,” with detractors claiming she lacked the mental ability to write and think the way she seemed to. This combination of renown and ableist skepticism seems to haunt Keller throughout her career, and even resurfaced recently with the #HelenKellerWasntReal hashtag on TikTok. Why were Keller’s accomplishments so heavily contested in her own time (and today), and how did she think about her fame?

KEN: Ableism sucks. The continual devaluing of Keller and other people with disabilities persistently undermined her public and literary career, and pained Keller tremendously. Her detractors used that ableism, and her embrace of political opinions sometimes controversial, to dismiss her ideas and her legitimacy as an original thinker. The skeptics who questioned Keller’s capacities during her lifetime pained, insulted, and infuriated her; as does today’s dismissal of Keller as incapable pain, insult, and infuriate modern people with disabilities. Keller’s fame gave her great opportunities while also opening her up to derision.

Keller and her lifelong companion and teacher, Anne Sullivan, in 1899 (Alexander Graham Bell / Public Domain)

LOA: In addition to casting doubt on Keller’s achievements, her critics used her disability as a basis to discredit her progressive politics on issues such as suffrage, economic injustice, and race (in one example, the Brooklyn Eagle, noting her support of Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs, wrote that her “mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development”). What were Keller’s political commitments and where did they spring from? And why did a public that eagerly embraced sentimental accounts of her education reject her writing in support of social justice for other groups?

KEN: While Keller’s political focuses varied throughout her long lifetime, she steadfastly embraced ideals of justice and equality, a belief in human capacity, and a commitment to compassion. She wrote that these ideals sprang from her experiences as a disabled woman and her religious faith.

Much of the reading public embraced her sentimentality but rejected her efforts to live out her ideals consistently and in all areas of life. For example, writing about loving the poor was one thing, but insisting that doing so meant creating safe employment opportunities, access to food and education, secure housing, and legal guarantees of the right to vote was more than much of the reading public desired to hear.

LOA: At the heart of the LOA Keller edition are two of her most enduring works: The Story of My Life, which she began as a student at Radcliffe College, and The World I Live In, a reckoning with readers’ questions about how she experienced life as a deaf-blind person. Why did you select these two works of Keller’s for inclusion? Do they reveal different facets of her mind and biography?

WATCH: Helen Keller in the 1954 documentary Helen Keller in Her Story (also known as The Unconquered)

KEN: I love these works because they are Keller’s insistence that she could think, communicate her thoughts, and accurately perceive life around her. That may sound basic, but others constantly doubted and dismissed her. These were her first literary accomplishments, and they laid the groundwork for the entirety of her adult life. These works were her stubborn claim to human legitimacy and adulthood. Their existence reveals her humanity as well as the resistance of others to that humanity.

As a historian, I often insist that the U.S. appreciates its activist heroes most passionately either after their deaths or near the end of their lives. Perhaps that is when we perceive them to be no longer threatening, when they cannot remind us of the sharpness of their analyses, or when we can soften their most vigorous critiques.

LOA: Among the most memorable scenes in The Story of My Life occurs when Keller realizes that Sullivan is spelling out the word “water” on her palm while running water over her other hand: “Somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me,” she writes. What are some of your favorite moments in the autobiographies and how do they enrich our understanding of Keller and her time?

KEN: Early in The Story of My Life, Keller includes several paragraphs in which she writes about climbing trees as a child, and particularly sitting in a tree during a thunderstorm. As someone who read books while sitting in trees as a child, I love this. Her tree experiences were disparately relaxing, a solace, terrifying, and exhilarating. This was her first published literary exploration of nature, a theme that continued throughout her literary career, and one of many mentions of tree-sitting.

These paragraphs foreshadow her sensory nature, her occasional enjoyment of being alone, and her desire to describe the world. It also reflects the naturalist and sentimental nature of the early twentieth-century U.S. literary world.

Keller in 1920 (CC BY 4.0)

LOA: Keller endured nearly two decades of financial struggle as an adult before accepting employment with the newly created American Foundation for the Blind in 1924, a role that would send her around the world speaking on behalf of people with disabilities. Can you discuss Keller’s second life as a public figure? How did her celebrity impact her writing?

KEN: Keller loved being a public figure. She moved in this direction after the reading public rejected her writing on non-disability topics. She quickly embraced her public life, however, and thrived on the decades of her resulting international travels, working and traveling on behalf of both the American Foundation for the Blind and the U.S. State Department.

Everything she learned broadened her writing. This ranged from writing about the devastation of post–World War II Japan, apartheid in South Africa, the delights of Egyptian pyramids, and the horrors of wars and militarization.

LOA: In your book A Disability History of the United States you make the point that “to understand disability history isn’t to narrowly focus on a series of individual triumphs but rather to examine mass movements.” Did Keller consider herself part of a movement, working with other people with disabilities? What is her legacy among disability activists or the deaf-blind community today?

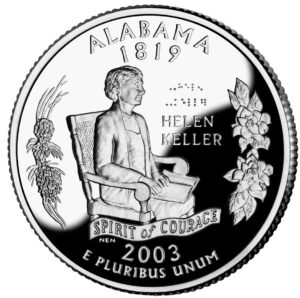

Keller as depicted on the Alabama state quarter (Public Domain)

KEN: An irony of Keller is that she was and is one of the world’s most famous disabled persons and advocated deeply for people with disabilities, yet had limited contact with organized movements of disabled people. Her legacy is thus complicated. She is both loved and sometimes resented.

Keller, however, did consider herself part of a movement for disability justice—and valued what she could do. The reality was that the inaccessibility built into the committee work, political organizing, and daily activist labor of the first half of the twentieth century generally made the labor of activism difficult for her.

LOA: Late in life Keller was treated to an array of accolades. The 1959 play The Miracle Worker, based on The Story of My Life, was adapted into a 1962 film that received five Oscar nominations, and President Johnson awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964. Posthumously, she was honored with a USPS stamp in 1980, and in 1999, Time magazine named her one of the twentieth century’s most important people. What explains her ascension as an American icon?

Keller and actor Patty Duke, who portrayed Keller in the 1962 play and film versions of The Miracle Worker (Public Domain)

KEN: As a historian, I often insist that the U.S. appreciates its activist heroes most passionately either after their deaths or near the end of their lives. Perhaps that is when we perceive them to be no longer threatening, when they cannot remind us of the sharpness of their analyses, or when we can soften their most vigorous critiques. Such is certainly the case for Martin Luther King, Jr., for example, and I believe it to be the case for Helen Keller.

In addition, Keller deserves to be an American icon. The successes of the disability rights movements and the women’s movements forced us to look to our recent past for heroes. Keller’s spotlight reflects her many successes as a literary figure, a political activist, a global communicator, and as a someone from whom many of us desire to learn.

LOA: What little-known fact or anecdote about Keller do you wish more people knew? What might surprise us about her as a person?

KEN: I love the stories of her breaking expectations in small and everyday ways. For example, in 1948, she flew into Australia en route to Japan. American and Australian officials met the sixty-eight-year-old woman with a tea party and an ambulance (just in case). She walked down the plane steps herself, as was her norm, and asked for Scotch instead of tea. No need of the ambulance. This was not a staged act of resistance, though her actions embodied resistance, but was simply Keller being Keller.

Keller and Sullivan in 1913 (Public Domain)

Kim E. Nielsen is Distinguished University Professor and Disability Studies Chair at the University of Toledo. She was the founding president of the Disability History Association. Her books include The Radical Lives of Helen Keller (2004), Beyond the Miracle Worker: Anne Sullivan Macy and Her Extraordinary Friendship with Helen Keller (2009), and A Disability History of the United States (2012).