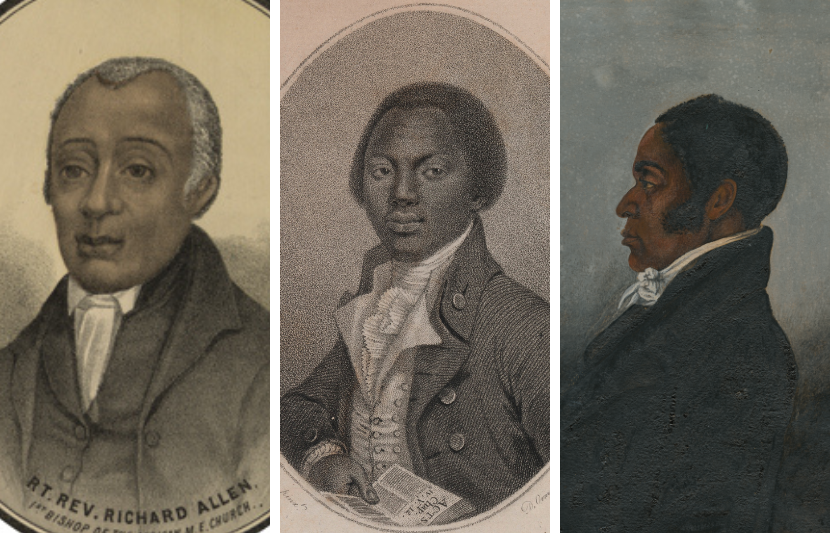

Portraits of a Black sailor (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), Phillis Wheatley (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History), and Absalom Jones (Delaware Art Museum)

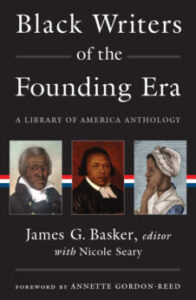

Longstanding efforts to deny Black Americans their rightful place among the founding voices of the United States have frustrated but never silenced a message of resilience and resistance stretching back centuries. With the recent publication of Black Writers of the Founding Era, editors James G. Basker and Nicole Seary present a remarkable archive that dismantles outdated assumptions about this pivotal epoch in our nation’s history, foregrounding firsthand accounts by African Americans enslaved and free, women and men, Northern and Southern. What emerges is a picture of a people assailed but unbroken by slavery and racism, as well as portraits of exceptional individuals—from soldiers to poets, politicians to mathematicians—whose writings provide invaluable insight into the animating principles of the American Revolution: freedom, equality, and political self-determination as matters not only of philosophy, but very survival.

Assembling this volume—the richest and most expansive of its kind ever produced—was no mean feat. Basker and his team scoured the country for more than two hundred pieces, including one by famed poet Phillis Wheatley that was discovered just a month before the book went to press. But this continuously shifting scholarly landscape, turning up new treasures even as vast swaths of material remain obscure (or lost for good), is to be expected when restoring to the historical record accounts and viewpoints that were, for much of the United States’ past, systematically ignored or suppressed. “The texts in this book chart the Black presence and make visible the Black experience in a period for which we lack even basic information about most of the Black population—names, birth and death dates, hometowns, spouses, children, relatives,” Basker writes in his introduction. “Hundreds of the burial grounds that might yield such information have been for centuries untended, forgotten, paved over.”

The exhumation and resuscitation of this crucial history is now definitively underway. In an interview with Library of America, Basker spoke about the arduous process of editing the volume, the striking contributions of women to the anthology, and what these transmissions from a nascent United States can tell us about the country we inhabit today.

LOA: Can you speak to the process of assembling this volume? What archival work did you and your team undertake to locate and compile these writings? What were some of the challenges?

James G. Basker: I have been working in the history of slavery, abolition, and the Black Atlantic for more than thirty years. In fact, the last book I did before this one for Library of America was called American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation, and many of the writers in that volume were African Americans, although the majority were white supporters of the antislavery movement at different times.

I sometimes call myself a literary archaeologist because I’m trying to dig up things that are hidden or buried in the past, and that touches on the archival challenges trying to gather this material. People famously did not preserve a lot of African American papers in the way that they would, say, those of George Washington or Thomas Jefferson. Nonetheless, a lot has survived.

Decorative tray depicting Reverend Lemuel Haynes at the pulpit of an integrated church, c. 1835–40 (Rhode Island School of Design)

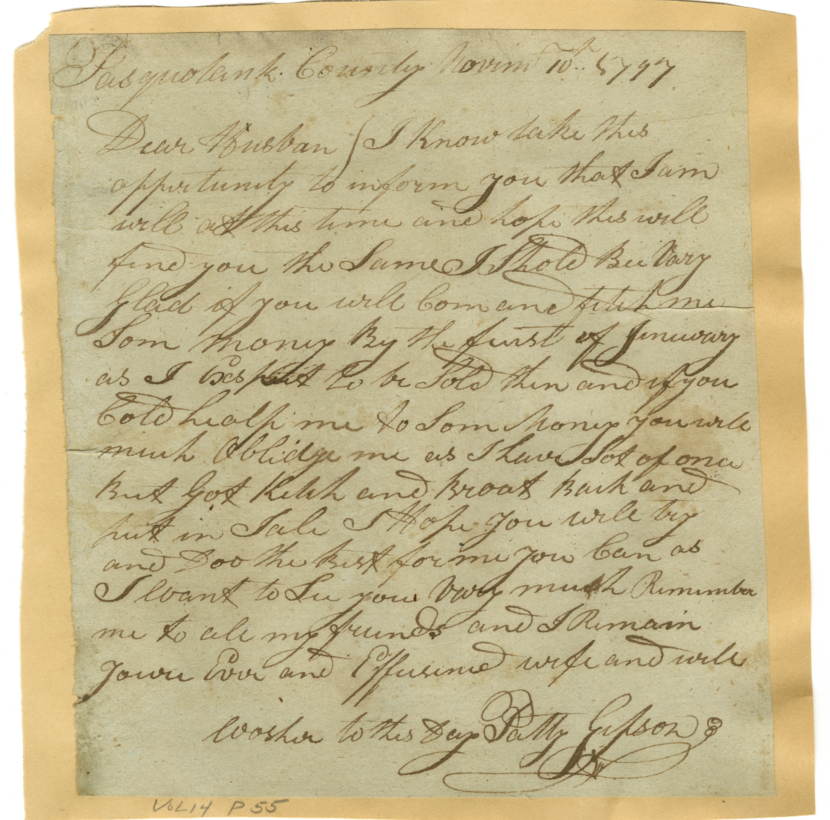

Sometimes it’s in a box in a historical society labeled “Africana,” with no other cataloging, and an invitation from an archivist there to look at the box turns up a letter from an enslaved woman in North Carolina to her husband in Philadelphia. More and more over the past twenty or thirty years, archivists are deliberately surfacing material, and scholars are discovering more and more all the time. In fact, a poem by Phillis Wheatley turned up just a month before we were going to press for this volume and the discoverer kindly allowed us to include it.

There are about forty different archives we found material in, and I’m indebted to the research assistants who did some of the legwork going to find these things. There were huge challenges when the pandemic hit because institutions closed and there was no access to these materials. In many cases staff were not even able to answer e-mail or provide digital images.

In the end, it’s a process that will continue. There is much more where these writings come from, and I hope that scholars and future generations of students will keep exploring.

LOA: An aspect of engaging with these texts, as you note in your introduction, is reckoning with all the missing pieces, the narratives that are left unresolved in the historical record. Could you talk about these lacunae in the archives and what it’s like working with a history that is being actively unearthed and pieced together?

JGB: This is a long-running problem in American history. The Dred Scott decision written by Justice Taney infamously said not only that slavery could go into any free state, but also tried to claim that Black people were not encompassed under the Declaration and the Constitution and had no rightful presence in the body politic. It was an attempt to make African Americans disappear from our founding story.

What excited me most about these materials, and seems to me most important, is that every single one of these texts brings into view a human being, a life story, that we may have lost altogether if that document hadn’t survived. With many of them the story is incomplete, but we get a glimpse of the dramatic moment—when a mother is petitioning a legislature to protect her children from being enslaved, for example, or when a former Black soldier in the American Revolution petitions for a pension. There are so many dramatic moments where we see a life vividly, where someone shone a light suddenly into the darkness, and it makes you feel compassion and empathy. It makes you aware of the lives of these people, and makes you want to know more. I think that’s the most important thing the book could possibly do.

A letter from Patty Gipson to her husband, November 10, 1797 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

LOA: Much of the rhetoric that’s being used in the founding era to justify revolution and American independence is taken up by Black Americans as a basis for their own liberation. Could you talk about the emergence of African American identity alongside American identity? Where do these syncretic senses of self come from at this historical moment?

JGB: One of the major implications of the materials in this book is that the civil rights movement in America didn’t begin in the 1960s or even in the Reconstruction period following the Civil War; it began within months of the publication of the Declaration of Independence. Literally five different writers in this volume cite the Declaration—beginning already in 1776, early 1777—as the basis for themselves claiming equal rights.

Indeed, the first and most enthusiastic interpreters of the Declaration are African Americans who want inclusion into this set of ideals, into a society that might enact and conform to them. Of course, that didn’t happen, although I think there’s evidence in these texts that pressure from groups of free Black people served as a conscience or stimulus to white legislatures in the North that did proceed to abolish slavery in Vermont, first of all, and then Massachusetts and Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

I think we can see with these documents that the campaigns and petitions by Black groups, and the arguments they made, had impact and influence on the establishment—not with success across the board, of course, and racism and exclusion were going to continue for two hundred years. But there was a beginning.

Portraits of Reverend Richard Allen (Library of Congress), Olaudah Equiano (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution), and James Forten (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

I think of the words of Akhil Amar at Yale Law School, who’s written about the founding era, and he talks about the Declaration and Constitution as the Big Bang of American democracy, or of democracy in the world, and I think that African Americans saw it that way as well. This was an expanding universe of opportunity and they wanted to be part of it.

One irony about the notion of African American identity also emerges in this volume. Throughout the founding era, Black people were often referred to as Africans or Ethiopians, and so on. But one of the writers in this volume, in 1782, uses for the first time the term “African American” to identify himself. He was a supporter of the American Revolution, he embraced its ideals. And by calling himself an African he wasn’t marginalizing himself. He was actually, from a position of estrangement, claiming that he was African American, including himself in the body politic of Americans for the first time. That’s an important dynamic in the history of this period, and in the history of Black agency when confronting the American Revolution and the establishment of the American Republic.

LOA: As the founding era comes to a close and we enter the period from 1800 up to the Civil War, we see the rollback of a lot of possibilities for Black Americans that emerged during the time of the Revolution. Could you talk about these missed opportunities, as you call them? What were some of the consequences of not incorporating Black Americans into the body politic of the nation from the beginning?

JGB: It is a perplexing thing to study, and I think it does dramatize huge missed opportunities. But as the 1780s and ’90s rolled on, the newly born United States was making progress, as most of us would see it today. There were seven states in the North, as I mentioned, beginning with Vermont 1777, that were abolishing slavery and passing emancipation laws. In the 1790s, Congress was hearing petitions from Black people. As for state legislatures, the Northwest Territory had been created in 1787, banning slavery; five free states emerged from that territory. Even George Washington, in his last will, tried to set an example for the country by freeing the slaves he owned (though he couldn’t free the ones that were held in dowry for his wife).

There were so many positive signs, even in the early years after 1800. New Jersey passed emancipation in 1804. In 1808, the United States and Britain abolished the transatlantic slave trade. Everybody would have said things were going in a positive direction.

I want every student to be aware of the sheer presence of Black people, in large numbers and in major contributing ways, during the founding era. They tend to be completely erased from the national memory of that period, and yet they were profoundly important and active, and contributed in so many different ways. Their stories matter.

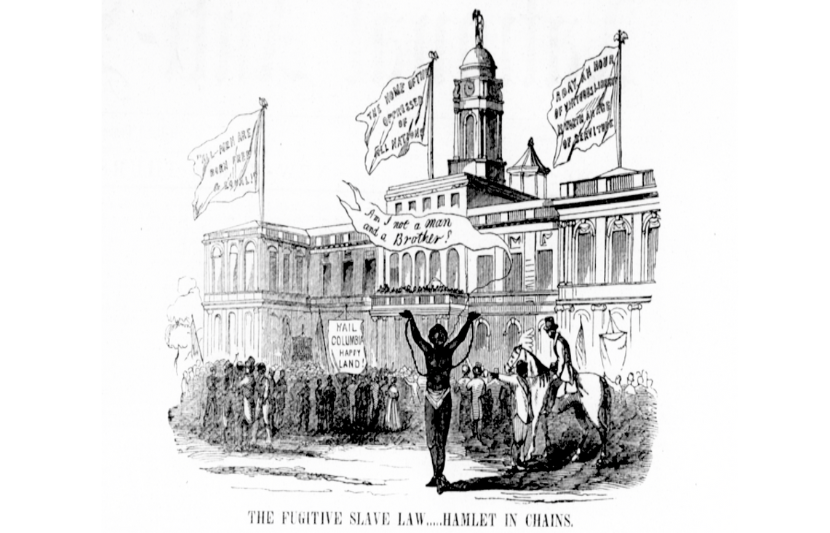

At the same time, economic forces were beginning to shift dramatically. The Louisiana Purchase opened up vast new territories twice the size of the thirteen states. The cotton gin had made the production of cotton fifty times more efficient. So the economic power that was steadily developing in the 1810s, ’20s, and ’30s, right to 1860, made the Southern states—more and more of them joining the union, like Alabama and Mississippi in the 1820s—a political power that was ungainsayable. They controlled the presidency and Congress, almost without exception, all the way through the 1850s—so much so that the legislation passing in the 1850s, the Fugitive Slave Act and other measures, were really rolling back the autonomy of free state courts.

James Hamlet, the first man re-enslaved under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, in front of New York City Hall (Public Domain)

It was a tremendous reversal of the momentum that had begun in the founding era. I think the 1850s were the worst decade in the history of the American republic, right down to the present moment, and it took a Civil War to blow up that power structure and begin forward movement again, with people like Abraham Lincoln leading the way, his Gettysburg Address turning back to the Declaration as a marker of our moral and political ideals. Reconstruction made some progress in terms of passing the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments and restoring some rights to African Americans. The long Jim Crow period compromised that progress, but then again in the twentieth century, we saw the arc of progress revive. I don’t see American history as a steady arc of one kind or another, but even between the zigzagging points up and down, I think progress has been achieved, although there’s still a long way to go.

LOA: In the anthology, there are many examples of Black Americans trying to engage with this white supremacist political system, a political system that was not built by them and that exerted an extremely unequal control over their lives. And then on the other hand, you have the emergence of Black institutions, specifically the Black church, as incubators for political organizing and liberatory thought. How did Black Americans seek to build their own political communities outside of the mainstream?

Portrait of Prince Hall (Public Domain)

JGB: It’s absolutely true that Black people, from the time of the Revolutionary War all the way into the nineteenth century, were—even when they were excluded from the political system and often denied civil or legal rights—nonetheless taking positive steps to organize themselves to build and support their own institutions and communities. The first African American Masonic lodge was formed by Prince Hall in Boston as early as 1775, and it was typical of these kinds of mutual aid societies. The first of those was mounted, ironically, in Newport, Rhode Island, a hub of the transatlantic slave trade. These mutual aid societies that formed in Newport, Providence, Boston, and Philadelphia sought to do many things: support widows and orphans, help people who’d lost their jobs or livelihoods, or were too ill to work. They had education programs for the children in their communities. And then there are the churches, and not just the AME Church that Richard Allen founded in Philadelphia, but also a Black chapter of the Episcopal Church and Baptist churches that were forming in South Carolina and Georgia.

These were ways that Black people who had been either excluded or discriminated against in established institutions were forming their own groups: mutual aid societies, fraternities, and especially churches, which would be the incubators for education, progress, political demands, and civil rights campaigns all the way through the twentieth century. And if we think about Martin Luther King, Jr., and so many other leaders of the civil rights movement, these were leaders of the church, leaders of community institutions, who were entering into national politics on behalf of their people. It’s a tremendously important dynamic, and we can see it in the book through the resurfaced public and private writings of the people who were forming these institutions.

LOA: Also central to the story of Black self-determination are the many examples of soldiers who either joined the Continental Army or the British Army. Could you talk about the experiences of Black soldiers during the war? Why might they gravitate to one or the other side in the conflict, and how do their stories complicate narratives about Black participation in the War for Independence?

JGB: The individual Black response to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War could vary across regions and the individual circumstances of the people involved. There were people who joined the Continental Army, often having started with militias that then formed the army. And there were also perhaps twice as many men who eventually went over to the British side, who saw this as an opportunity to liberate themselves. They’re sometimes referred to as British loyalists, but they weren’t doing it out of loyalty to George III; they were doing it out of an opportunistic effort to emancipate themselves and take control of their lives. The British seemed to offer that, and in many cases delivered it.

But it’s interesting to me that in the North there were free Black people who were already enlisted in local militias when the war broke out. You can look at Lemuel Haynes, who came from Granville, Massachusetts, with the local militia, and arrived in Boston the day after the Battle of Concord and Lexington. He was part of the Siege of Boston and then later the Battle of Ticonderoga. There were at least five thousand, maybe as many as eight thousand, African Americans who fought on the American side in the Revolution, and many of them quite heroically. We can forget how present they were. The first man to die at Valley Forge was an African American. At Yorktown, a French officer who recorded in his diary what he observed estimated that more than twenty percent of the soldiers on the American side were African Americans.

Soldiers at the Siege of Yorktown, including a Black soldier of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment (Brown University)

I estimate that if the five thousand Black soldiers in the American Revolution had on average two children every generation, in ten generations there might be as many as five million people alive today in the United States who could claim descent from Black veterans. People like Henry Louis Gates, Jr., at Harvard, who have Black ancestors who fought in the Revolution, have gained membership in the Sons of the American Revolution. The Daughters of the American Revolution long ago began to accept African Americans as members. This should help us to rethink our body politic today, who our real founders were as an interracial population and not just white people.

LOA: Another significant aspect of this book is the presence of women’s voices, especially given that many of them lived with what you call the “double disadvantage” of being Black and being a woman. What are some of the difficulties you find in locating and contextualizing the writings of women from this era? What ideas or themes emerge in their writings that are less present in those of their male counterparts?

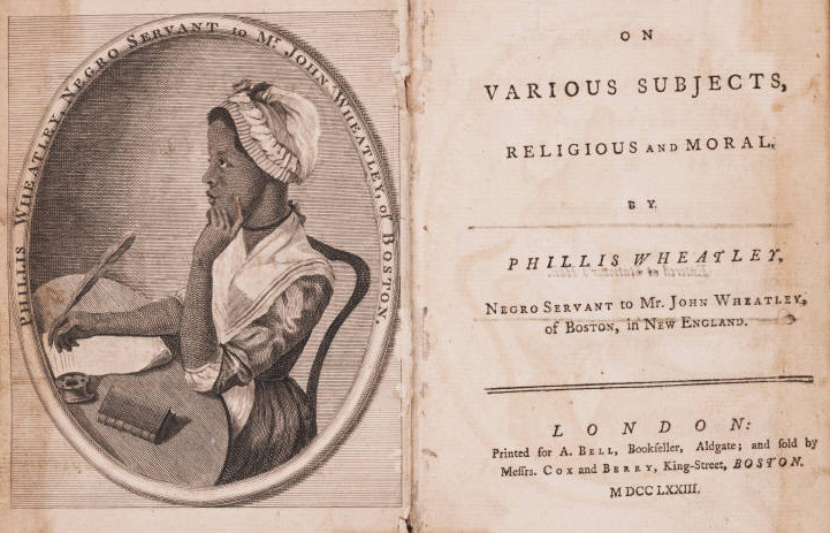

JGB: There are twenty-five women represented in this book, at a time when Black women had lower rates of literacy than Black men. And the most powerful figure in the whole anthology is Phillis Wheatley, who is a unique thinker in the founding era. She has the most texts in this book, she’s the most powerful actual literary figure. She published a book of poems in London and was well known throughout the colonies as a very accomplished poet.

What we’ve lost track of, because we think of her as the mother of African American literature, is that she was also a political actor on the American side during the Revolution. Even before the war, she’d written poems about the Boston Massacre, about the repeal of the Stamp Act. When Washington was appointed commander in chief, she wrote a huge poem of tribute to him that eventually was published in Virginia newspapers and The Pennsylvania Magazine. She writes poems supporting the war all the way through, really putting her life on the line. If she had been captured, she could have been severely punished, imprisoned, or even enslaved and sold off to the Caribbean. I think she deserves to be known actually as the poet laureate of the American Revolution.

Phillis Wheatley, frontispiece and title page of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, 1733 (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

The other women are not so much public figures like Wheatley, but the documents that survive show them doing the important work of family life, of protecting their children, and in some cases submitting petitions to free their children. In one instance, a woman who in fact legally “owned” her husband in order to protect him from mistreatment in her own state, eventually petitions the government to allow her to free him.

Elsewhere, there are women writing private letters. One from North Carolina is from a woman who’s about to be sold at auction, begging her husband in Philadelphia to send enough money to redeem her before she’s sold away. A couple of women in Sierra Leone are desperately trying to raise their children in horrible circumstances; letters survive begging the colonial authorities for some soap to wash their children or for a burial shroud to bury a husband who’s just died.

These documents open a window into the personal and domestic lives of extraordinary women who had the courage and tenacity to fight to protect their children and their spouses, and their texts are especially valuable, because this is among the hardest worlds to gain access to as a researcher.

LOA: Are there pieces in the anthology you’d recommend to readers who may be less familiar with the era or reading primary historical documents? What material here could be most compelling to a layperson?

JGB: I’ll point to two. One is a poem by Lemuel Haynes, the soldier I mentioned earlier. He wrote a poem about the Battle of Lexington which, for all we know, may have been the first battlefield poem ever written in American history, let alone the first by a Black poet. That poem survived in manuscript, but it wasn’t really known and published until the 1980s. It’s a very simple ballad, written by a soldier living in the field, about the Battle of Lexington—no doubt he heard a lot about it from survivors. It’s simple enough that school kids can read it with understanding, and it reframes things for us to think that here is a Black writer, a person who wanted to write a poem recording this event. We think of “Paul Revere’s Ride” by Longfellow as the most important Revolutionary War poem, but Haynes’s poem is almost an eyewitness account, and he wrote it decades before Longfellow wrote his.

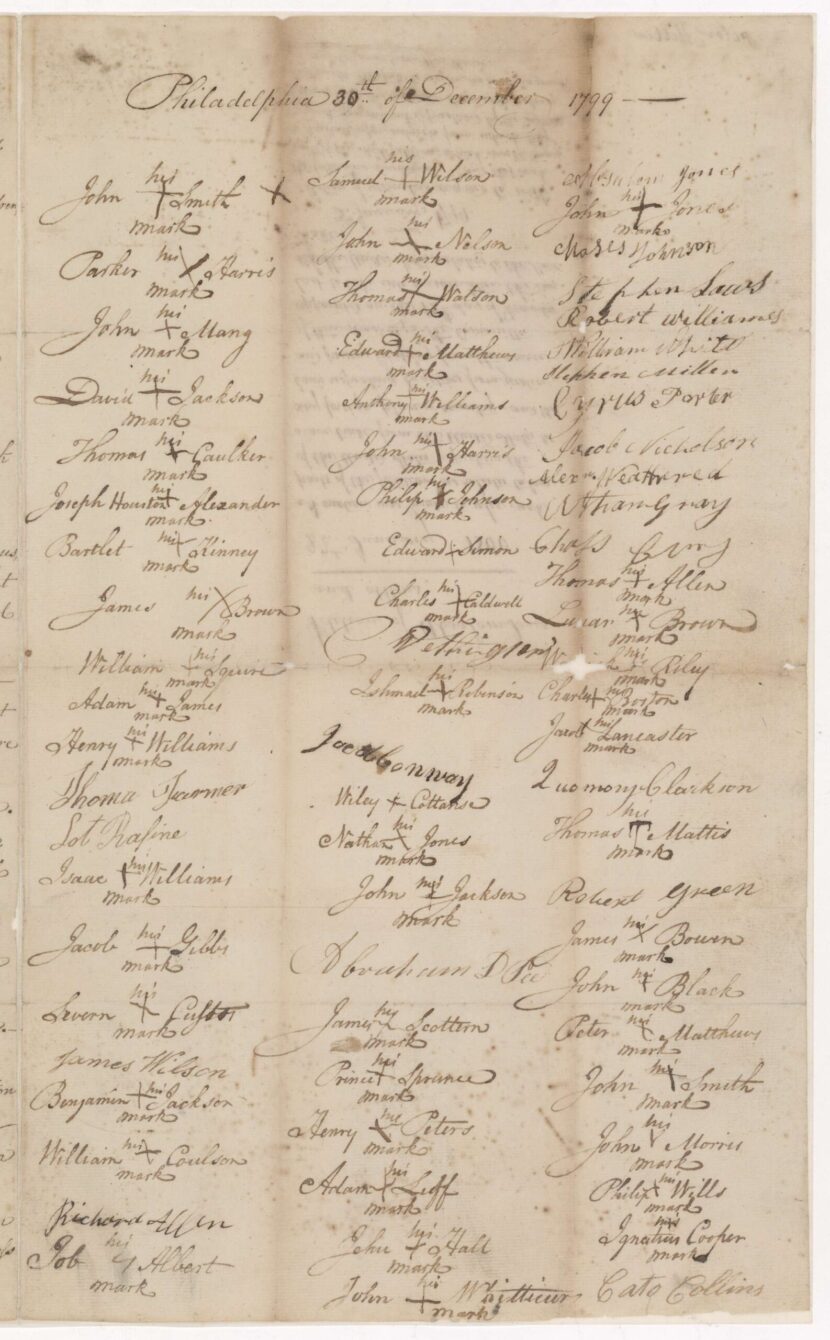

The other piece I’d name is from the other end of this period. In December 1799, a group of seventy-one African Americans from Philadelphia signed a petition addressed to the U.S. Congress. It was a call for civil rights and an end to the clandestine slave trade. It cited the Declaration and the Constitution. It pointed out that the Constitution did not mention Black and white people as having different rights, and so therefore these petitioners were arguing that they were included under the protections of the Constitution.

It’s very important to notice—and this is illustrated in the anthology—of the seventy-one signatures on that petition, only twenty of the signers were literate and could write their whole names. The other fifty-one could only put an X, but their names were written beside the X by a clerk of some sort. They wanted their names recorded on that petition at a time when it could really be dangerous to demand these rights from Congress. It’s a tremendous act of courage.

Signatures on a December 30, 1799, petition to Congress by Absalom Jones and others, seeking an end to the slave trade (National Archives)

It’s also a moment when the United States Congress missed maybe the biggest opportunity in history. For two days they debated this petition, which was brought to the floor by a congressman from Massachusetts named George Thatcher. The Southern congressmen reviled it, talked about it as French-revolutionary liberal insanity. They didn’t want—couldn’t imagine—Black people voting and getting elected to Congress. In the end they voted it down 85-1. But if that petition had been acted on positively, one can only imagine how different the arc of American history would have been thereafter.

LOA: If you were teaching this material, how would you get students into the mindset to engage with the subject matter? How can contemporary readers make the intellectual, ethical, and rhetorical leap from the present to engage with the ideas and ideals contained in these documents?

JGB: There are so many ways to approach it. First of all, there is no uniformity to this material. We have many different kinds of voices, so students need to understand that there are no easy generalizations here. They’re going to find, as they would in white history, complexity and variety. They’re going to find different life stories, some miserable and suffering, some highly successful and prominent, and everything in between.

I want every student to be aware of the sheer presence of Black people, in large numbers and in major contributing ways, during the founding era. They tend to be completely erased from the national memory of that period, and yet they were profoundly important and active, and contributed in so many different ways. Their stories matter.

For all students, empathy is the most important faculty that we cultivate, whether we’re reading fiction, poetry, or historical documents from a distant period in which the language and the frame of reference are foreign to us. I would be encouraging students to try to enter imaginatively into the world that these writers occupied.

To that end, I think it’s important to try to read these documents aloud. In some cases, that’s to get the phonetic spelling to be intelligible. But reading aloud helps students hear what the words are and what the meaning is, and helps them to enter vicariously into the lives of these people and understand their experiences and attitudes.

The way the anthology is arranged, with two hundred separate texts and headnotes that provide context for each, invites close reading, selecting a text and really working through it. And it also invites students to understand that thinking about history has to be document-based, evidence-based. We may have impressions or preconceptions that we bring to bear, but if we’re really going to understand people and know what their lives were like, we have to look at what they actually wrote and said and did.

Lastly, I hope some readers will also become creative adapters. There are stories here that should be films, that should be plays on stage, that should be songs, children’s books, or series produced on the Internet. There are so many interesting human stories here that could be fleshed out by the next generation of creative people, and that’s what I wish for.

A Black woodcutter in Nova Scotia, 1788 (Public Domain)

James G. Basker is President of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History and Richard Gilder Professor of Literary History at Barnard College, Columbia University. He has written and edited many books including, for Library of America, American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation (2012).