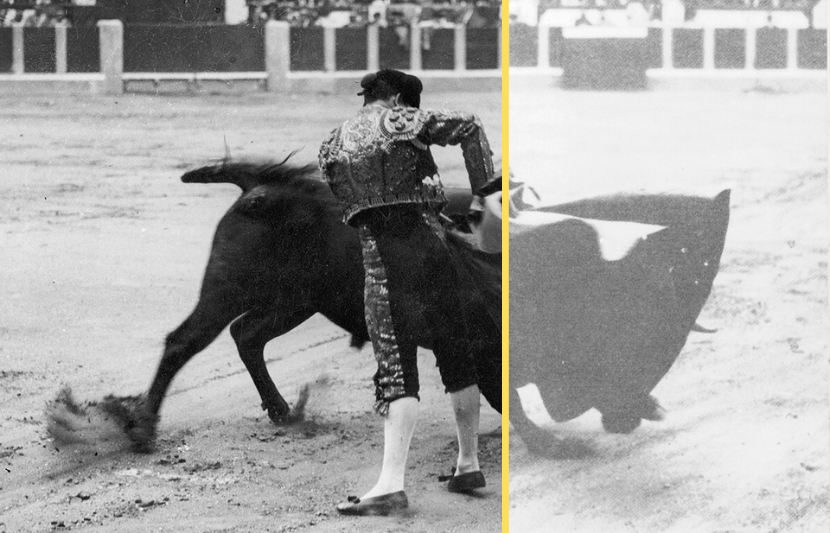

Before-and-after image showing restoration of an image from Death in the Afternoon.

Spare, limpid, sharp, impressionistic, Ernest Hemingway’s writing style reflects, at once, the journalist’s credo to faithfully document reality and the modernist’s mission to plumb the depths of experience and observation, going beyond obvious surfaces to, in Ezra Pound’s immortal slogan, “make it new.” Perhaps no other work by Hemingway balances these two modes of seeing more clearly than Death in the Afternoon, the author’s 1932 investigation into the centuries-old spectacle of Spanish bullfighting. A hybrid text combining personal anecdote, philosophical rumination, sociological inquiry, and a glossary of terms reminiscent of a guidebook, Death in the Afternoon is also distinguished by an unusual but, to Hemingway’s mind, necessary additional component: photography.

“I hope some day to have a sort of Doughty’s Arabia Deserta of the Bull Ring,” Hemingway wrote to his Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins in a 1925 letter, “a very big book with some wonderful pictures.” Even before he began writing Death in earnest in 1930, the author was envisioning something akin to a deluxe edition, replete with imagery he believed could transport readers inside the ring with a visceral immediacy lacking in written language. (“I have not described certain things in detail because photography has been brought to the point where it can represent some things better than a man can write of them,” he told Perkins.)

First-edition cover of Death in the Afternoon (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1932)

On a 1931 sojourn to Spain, he completed research for the book and gathered photos and postcards for inclusion. Critically, these images were not padding or decoration, but a central part of the artist’s vision. In a series of contentious exchanges with the cost-conscious Perkins in 1932, Hemingway argued for printing as many of the pictures as possible in the forthcoming book.

“It may be that a hundred illustrations is a grotesque and impossible number, impossible to do ‘in these times,’” he wrote. “But Max, if you think about the trend of these times, other than their financial trend, you will know the value of pictures and that they will do more for the popularity of the book than any other thing.” Elsewhere, the haggling continues: “If there has to be a compromise between sixteen and one hundred that compromise is not sixteen nor is it thirty two.”

Ultimately, eighty-one photographs made it into the published version of Death in the Afternoon. Paired with the author’s detailed, dramatic captions, the images succeed in capturing what Hemingway, in the book’s opening chapter, called “the instant and unexpected” reaction of the newcomer to the bloody spectacle of bullfighting. Likening the uninitiated viewer to someone drinking wine for the first time, Hemingway pronounces that he will “know whether he likes the effect or not and whether or not it is good for him.”

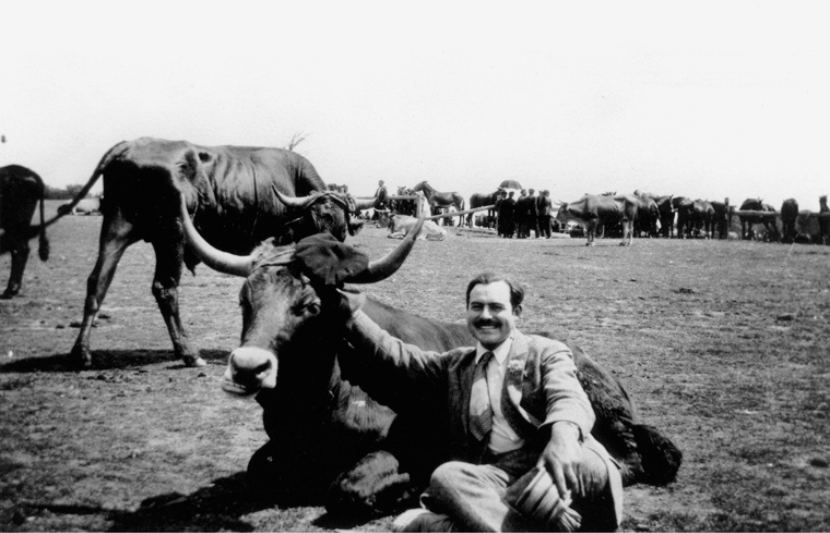

Hemingway with a bull near Pamplona, Spain, in 1927 (Public Domain)

Short of actually sitting in the stands, these kinetic, violent, and undeniably romantic images offer some of the clearest views available of the corrida de toros. In the 1932 first edition of Death in the Afternoon, however, the reproductions of Hemingway’s chosen illustrations tended to come out dark and somewhat blurry and, in the decades since, the quality progressively deteriorated in reprints, resulting in muddy and faded-looking pictures. But in Library of America’s edition of Hemingway’s bullfighting book, included in our recently published A Farewell to Arms & Other Writings 1927–1932, edited by Robert W. Trogdon, all eighty-one photographs can be seen as Hemingway intended, in their full vitality and documentary immediacy.

Along with restoring expletives removed against Hemingway’s wishes in A Farewell to Arms and fixing numerous typographical and other textual errors introduced into his most famous novel by typists and compositors, the volume features fresh scans of the original prints and postcards gathered for Death in the Afternoon, which are held at the Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. We thank the Kennedy Library’s talented archivists for their expertise in reproducing this invaluable material.

Below, we present eight of these rescanned images side-by-side with the versions from the original 1932 edition so you can see the remarkable differences. Drag the slider from one side of a picture to the other to reveal never-before-seen levels of clarity, contrast, and detail, bringing these archival snapshots to life as never before. Hemingway’s original captions accompany each photo.

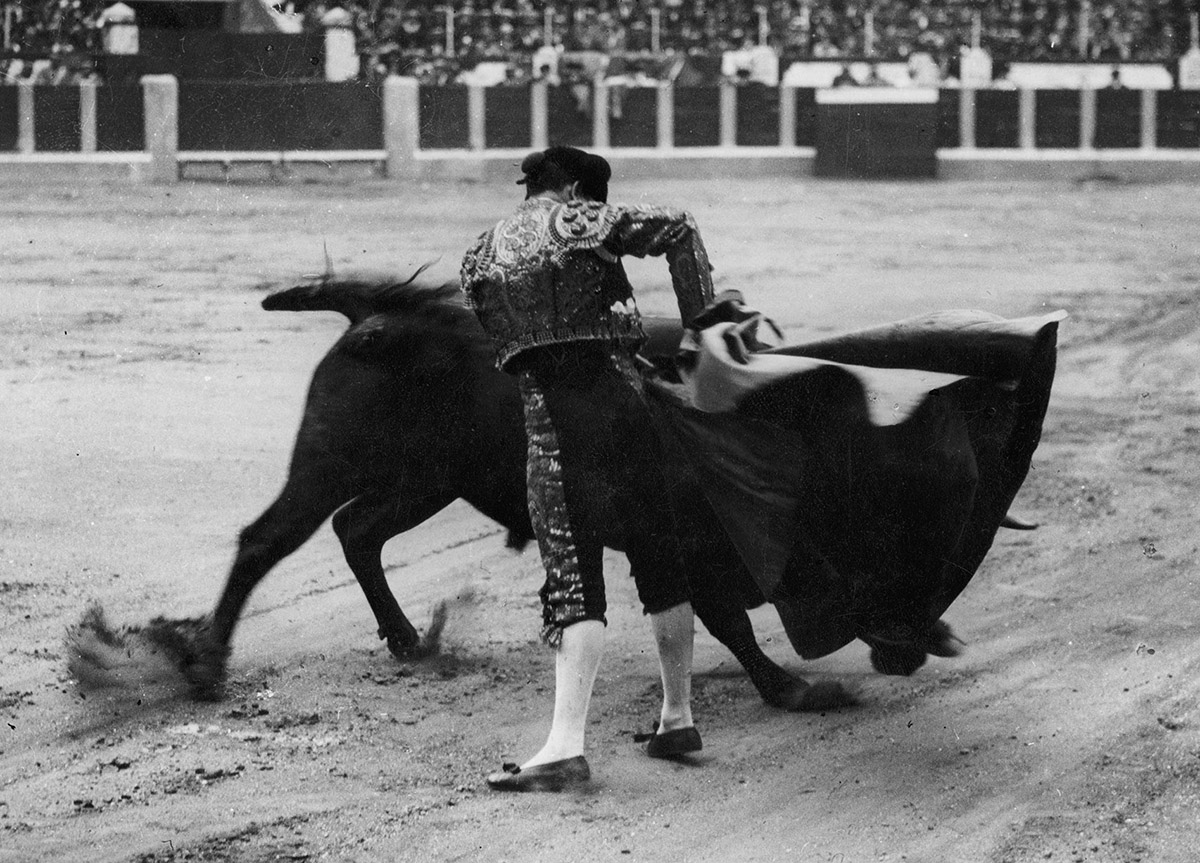

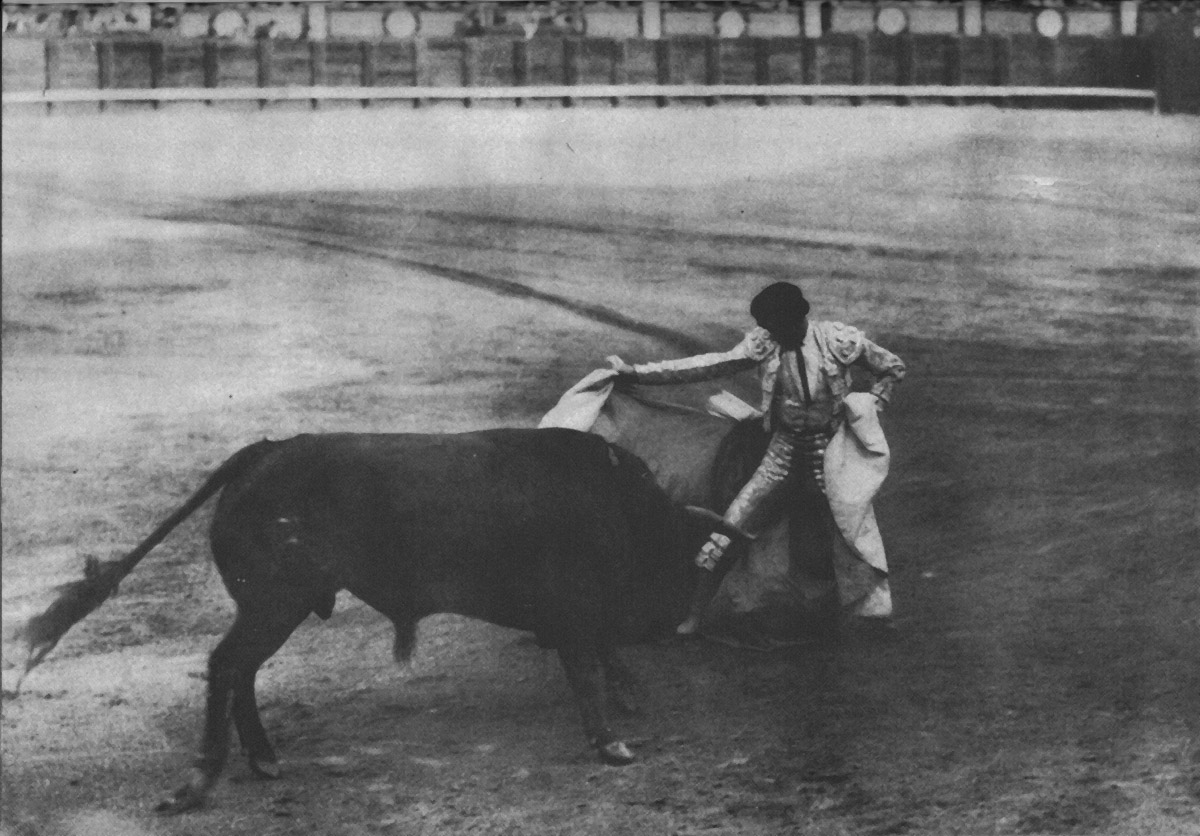

Gathering the cape toward him at the end of a series of veronicas to wind the bull around him like a belt, his right leg pushed toward the bull in that bent slant, which will be copied but never made truly until another genius comes in the same twisted body—the media veronica of Juan Belmonte. This pass is the end of a series of veronicas and serves to fix the bull in place and allow the man to walk away.

The end of the faena. Luis Freg in the hospital with a cornada in his chest. Note the scars on the right leg, the scar in the left armpit, and the unplaited lock of hair, that when braided makes the pigtail that was formerly the caste mark of a bullfighter.

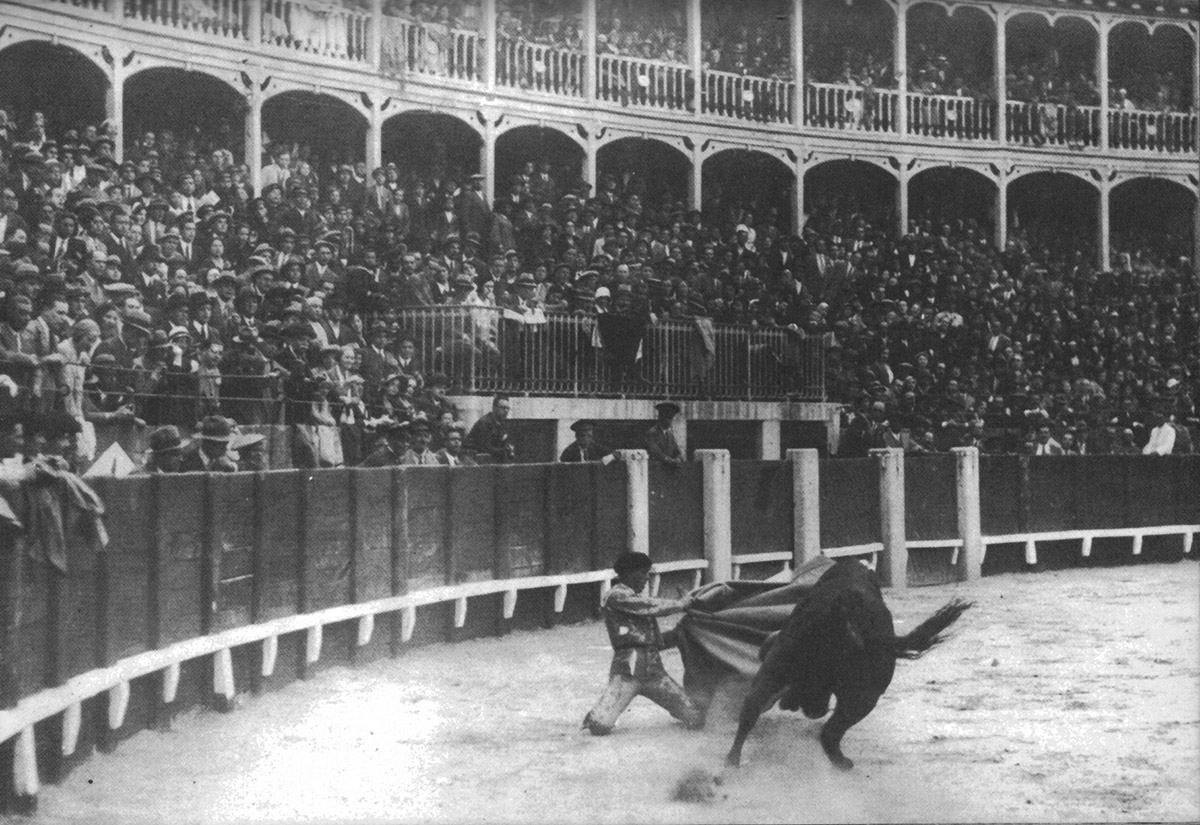

Joselito taking a bull out a step at a time from the querencia or position he has taken by the barrera; talking to the bull, working on the eye furthest away from the man with the end of the cloth that he imparts a swinging, flicking motion to with his wrist; exposing his own body to give the bull confidence that there is something to charge and yet keeping the animal’s main point of vision on the cloth and controlling his impulse to charge with that wrist movement. A brave bull is easy to work with if the man is brave and technically sound; it is the cowardly bull and the uncertain bull that call for the most intelligent and careful handling since they will charge as fast as the brave bull but there is no way of knowing when the charge may come.

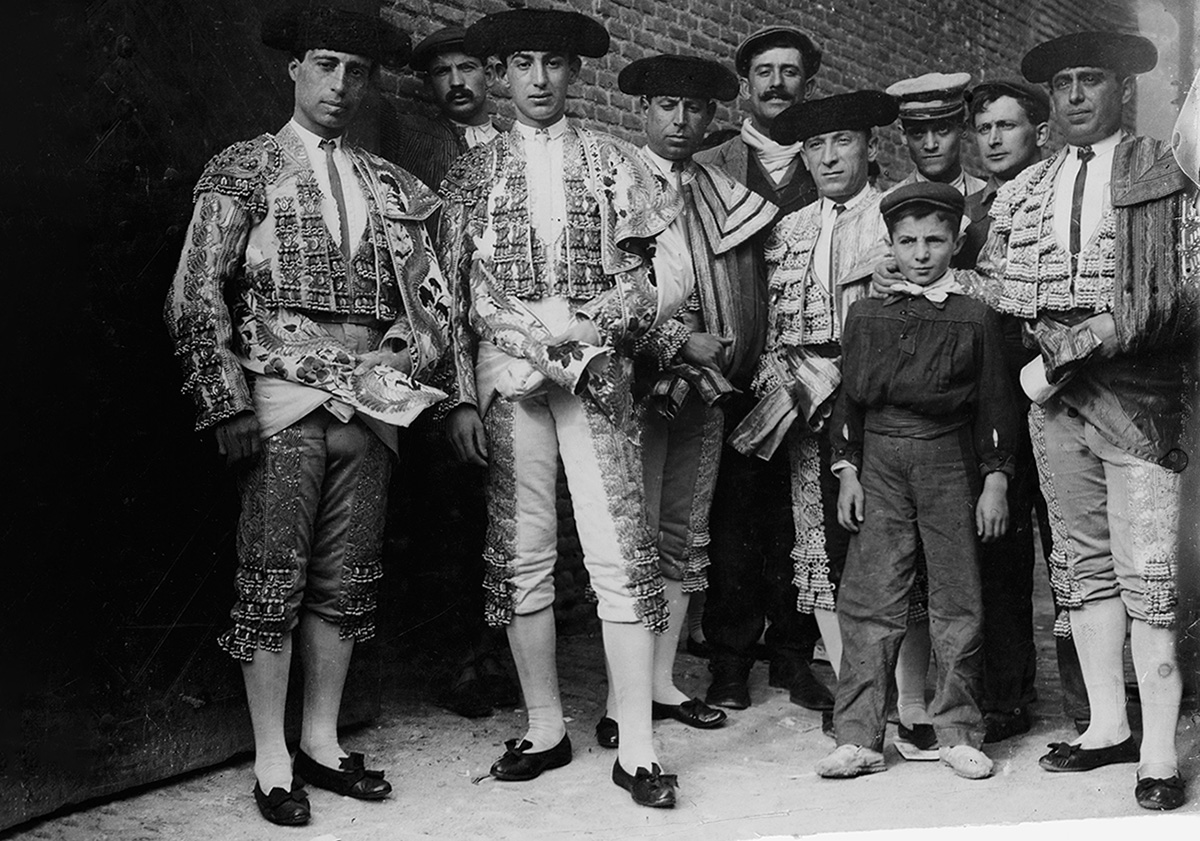

Rafael Gomez y Ortega, called El Gallo, standing in the entrance to the Madrid ring with his younger brother, José, called Joselito or Gallito, at the start of Joselito’s career as a matador. El Gallo is on the left, Joselito beside him. Fourth from the left is Enrique Berenguet, called Blanquet, the confidential banderillero of Joselito. The matador on the right is Paco Madrid of Malaga.

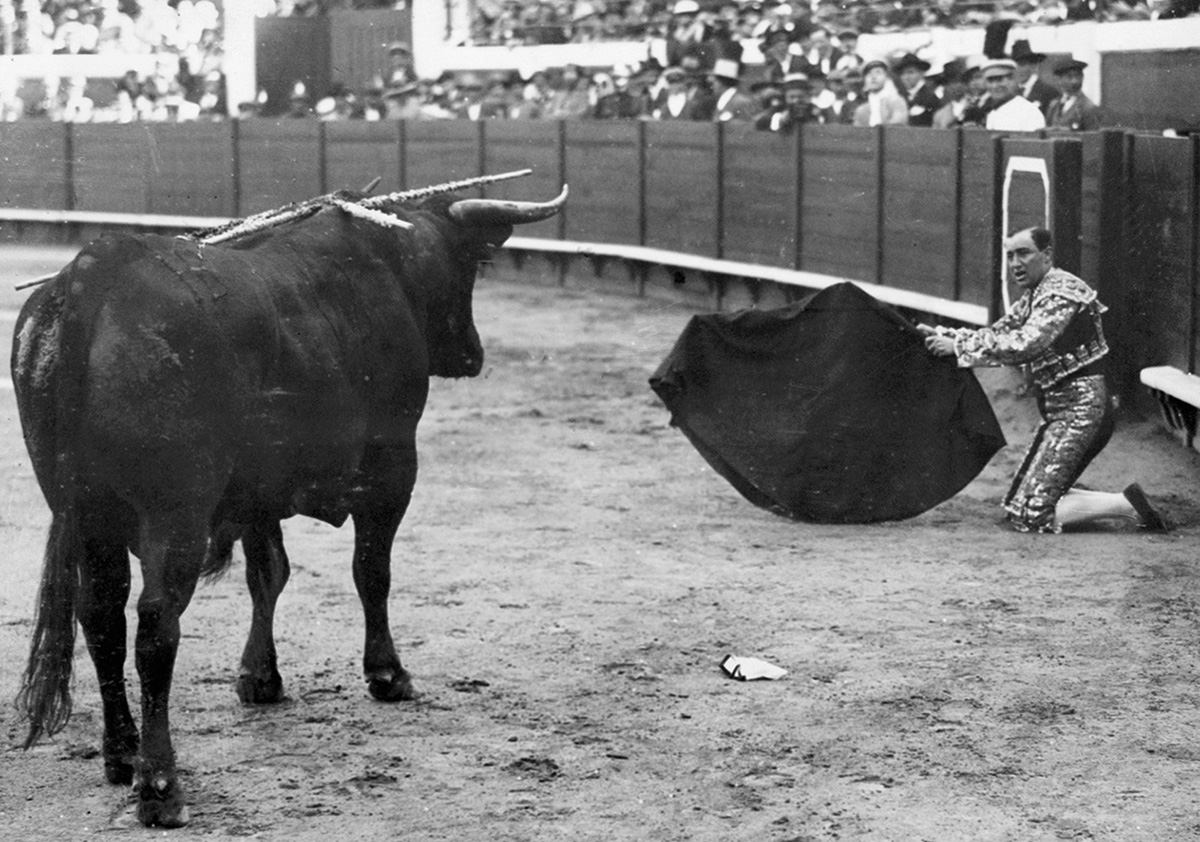

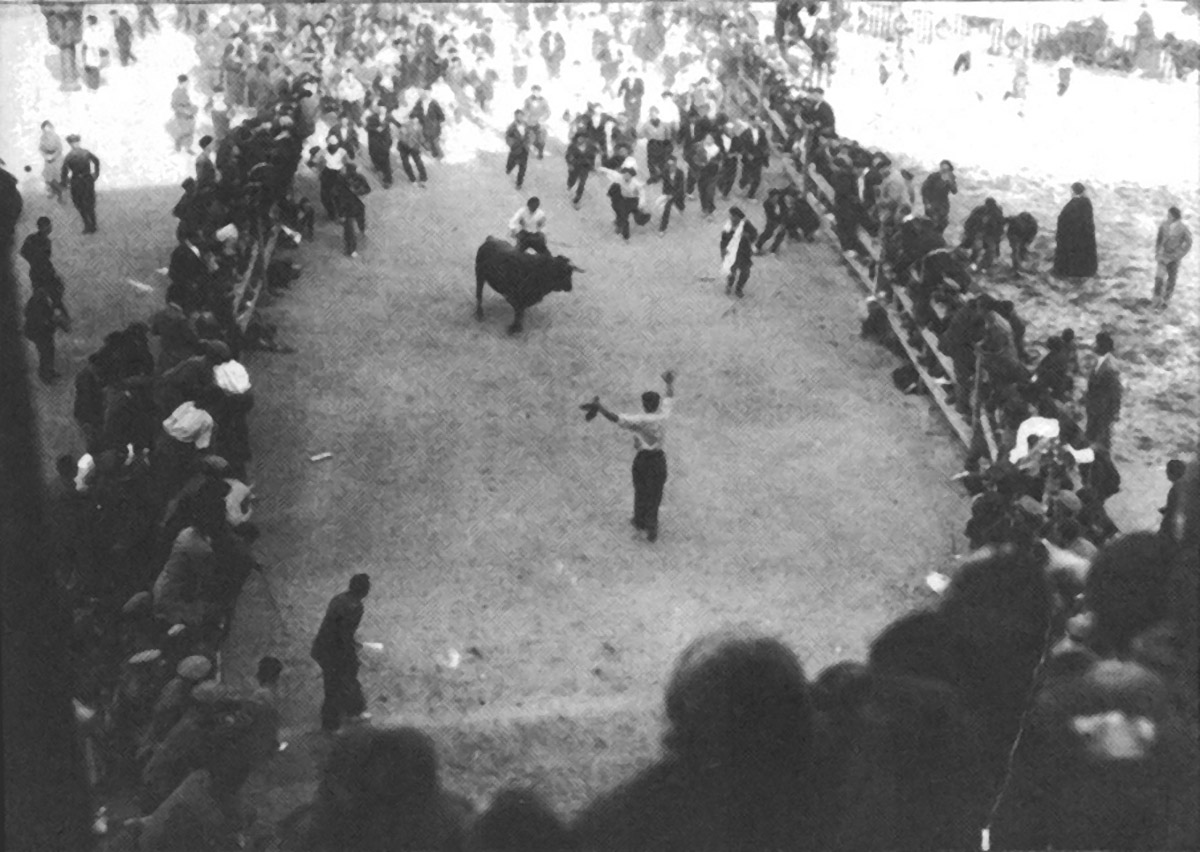

Joselito the spring he was killed, fat and out of condition after a winter in Lima, Peru, citing an uncertain bull to charge. The bull is slow to start and Joselito, reluctant to rise from his knees and admit his proposal to pass the bull with both knees on the ground was a failure, has just taken out his pocket handkerchief and thrown it at the bull to start him.

Marcial Lalanda making the quite of the mariposa or butterfly. Moving backward across the ring, the folds of the cape swing lightly. It takes great skill and knowledge of bulls to do properly or at all.

Marcial Lalanda in a cambio de rodillas made when the bull first comes into the ring.

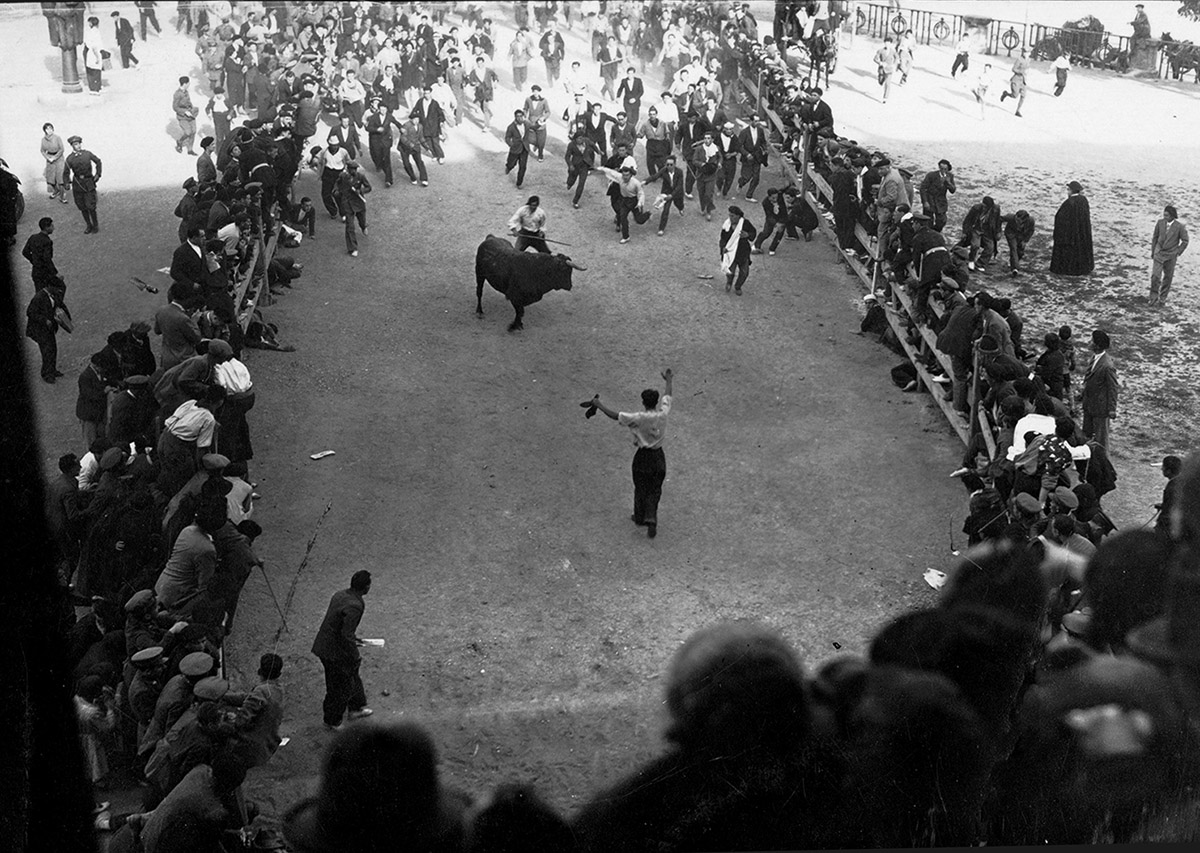

The highly paid Cagancho often kills like this from cowardice while in Navarra amateurs do this for fun.

Ernest Hemingway: A Farewell to Arms & Other Writings 1927-1932 is kept in print with a gift from Michael J. Ettner in memory of his father, John Francis Ettner, to the Guardians of American Letters Fund.