Detail from Lavinia at the Altar, (c. 1565) by Mirabello Cavalori, showing the moment Lavinia’s hair catches on fire (Public Domain)

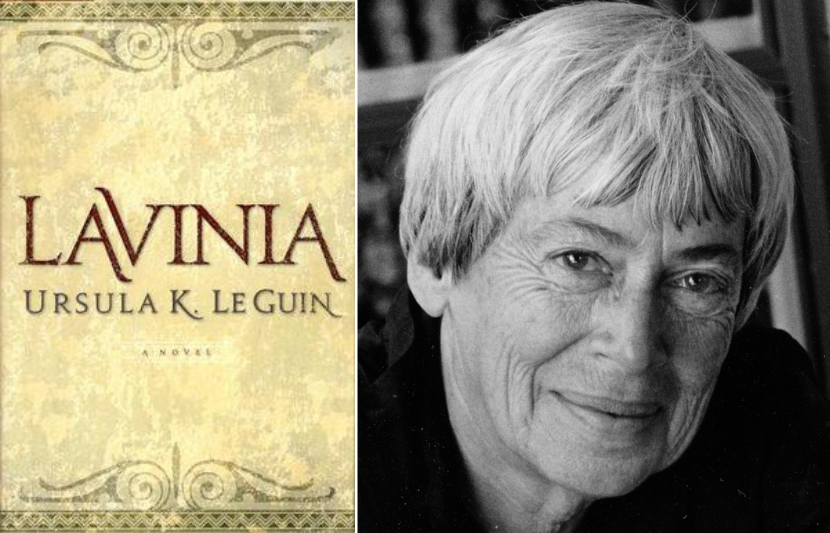

In this guest post, award-winning translator Sarah Ruden shares her correspondence with Ursula K. Le Guin about their shared fascination with Lavinia, the princess depicted in Vergil’s epic poem the Aeneid. Le Guin’s own spin on the myth, Lavinia (2008), was her final novel; it appears in the new LOA edition Ursula K. Le Guin: Five Novels.

Sarah Ruden (photo: Adrienne Malane)

In 2008, I moved from a small third-floor room (almost a garret, I told myself) in West Philadelphia to an apartment at Yale Divinity School. I had been translating Greek and Roman literature, and now, in my forties, I was going to learn Hebrew and see what happened.

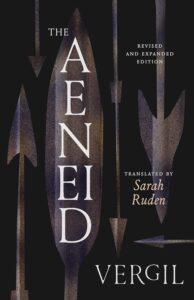

The Divinity School is the poorest, surliest, and hardest-drinking division of Yale, and while I was there, my translation of Vergil’s Aeneid came out (as had most of my other books) at a comically bad time and place. It was now near the start of the Great Recession, and I was surrounded by theology professors and ministerial candidates; there was nobody to encourage me in my ambitions as a poet and literary translator.

The Aeneid, translated by Sarah Ruden (Yale, 2008)

But then I heard from the writer Ursula K. Le Guin, whom I had revered from my teens, when I read the first three Earthsea books and the short-story collection The Wind’s Twelve Quarters. She thought that my Aeneid in English was beautiful.

What a shockingly old-fashioned judgment, but at the same time it seemed just like her, just like the openness and sympathy that allowed her to pour out so many works full of pure, deep literary pleasure. She sent me a copy of her own latest book, Lavinia, about the speechless princess over whose pending marriage Italy explodes in war in the Aeneid.

Her Lavinia is her original simple self, loyal to her difficult home, passive in the face of upheavals, later a tender wife and mother. But at the same time, she has her own thoughts, her own self-protective life; she is a worthy partner in conversation with the time-traveling Vergil, who in historical reality elected to represent her in a depressingly painterly way.

Lavinia by Ursula K. Le Guin (Harcourt, 2008)

In Vergil’s epic poem, Lavinia stands still, engulfed in an omen-bearing fire, while her father performs a traditional rite. Later, in her desperate weeping when the war outside becomes a death match between her parents and death moves toward her first betrothed, Lavinia is compared to a piece of superior material craftsmanship. In a simile adapted from Homer, the red blotches from her fierce blushing and uncontrollable weeping are compared to red dye on a piece of ivory; Vergil adds that her face is like roses and lilies bunched together, a quaint, jarring invocation of the garlands of leisure and festivity.

In Le Guin’s Lavinia, the young girl is far from mindless, far from an object. The poet’s torment over the violence and the contradictions of history finds a resting place in her goodness.

“Tell me,” he said, “have they come yet, the Trojans?”

A word I did not know. “Tell me who they are.”

“You’ll know who they are when they come. Latinus’ daughter, I am—” He hesitated—“I am searching for my duty here. How much is it right for me to tell you? Do you want to know your future, Lavinia?”

“No,” I said at once. Then I sought in my own mind for my duty, or my will, and finally said, “I want to know what’s right to do, but I don’t want to know what’s to come of it.”

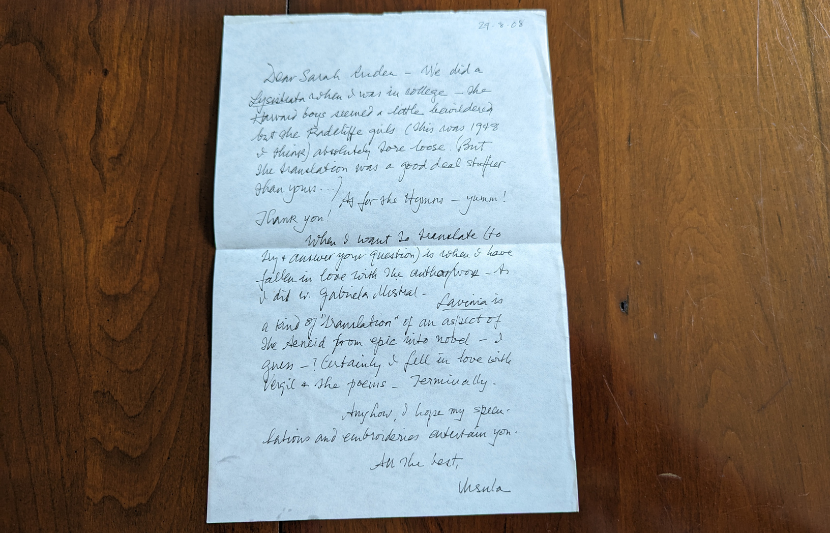

Le Guin wrote to me, “Lavinia is a kind of ‘translation’ of an aspect of the Aeneid from epic into novel—I guess—? Certainly I fell in love with Vergil + the poems—terminally.” I think that this embrace was central to her art. Le Guin was a loving person; she took things as wholes, unreservedly. She was not afraid to have a human relationship with evil, with death, with all the horrors of history.

Letter from Ursula K. Le Guin to Sarah Ruden (courtesy of Sarah Ruden)

These days, I am winding up a book of essays for Library of America about the poems of a very different author, Sylvia Plath. Plath was anxious about nearly everything, and hated and overidealized people by turns. But she and Le Guin both leave me exhilarated about the beneficent power of women’s minds and voices in these unendingly bad times.

Milton’s characterization of his own role as a poet, “They also serve who only stand and wait,” is generally truer of women than of men, and women authors seem to have a special role in facing the beauty and ugliness of the world as a single entity—one that needs recognition, that needs attention, just as it is.

Sarah Ruden is a leading translator of the ancient literature of the West. She has won Guggenheim, Whiting, and Silvers grants, and numerous other awards. Her forthcoming I Am the Arrow: The Life and Art of Sylvia Plath in Six Poems will be published by Library of America in 2025.

Ursula K. Le Guin: Five Novels

The Lathe of Heaven | The Eye of the Heron | The Beginning Place | Searoad: Chronicles of Klatsand | Lavinia

This volume in the definitive Library of America edition of Ursula K. Le Guin’s collected works brings together for the first time her five remarkable standalone novels. Not part of her Hainish universe or other series, these books illuminate in unexpected ways Le Guin’s central concerns with power and gender, human freedom and creative possibility.