andré m. carrington (University of California) and Afrofuturist influences and authors

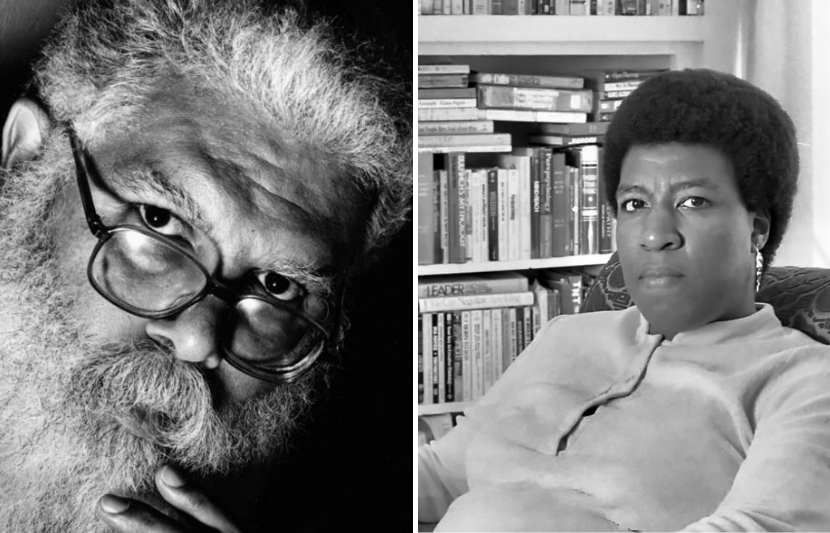

Afrofuturism is a time machine, offering readers not just speculative visions of tomorrow, but voyages to alternate pasts, remixes of the present day, hypotheticals, counterfactuals, and layered histories. Where innovators like Octavia E. Butler and Samuel R. Delany blazed new routes for Black authors expanding the frontiers of fantasy and science fiction, contemporary practitioners like N. K. Jemison, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, and Victor LaValle continue to journey outward and inward, mapping an ever-expanding universe of experience and creativity.

In the recently published The Black Fantastic: 20 Afrofuturist Stories, editor andré m. carrington collects some of the leading voices in this burgeoning literary movement. “The freedom to harness the imagination that Black creatives put into practice is as fundamental a right as breathing,” he writes in the volume’s introduction. “On the shoulders of generations of stargazers, inventors, and literary visionaries, today’s Black SF writers are carrying on a tradition with deep, far-reaching roots.”

Below, carrington discusses Afrofuturism’s relationship to genre fiction, its embrace of humor and wit, and its far-ranging influences and antecedents, from Daughters of the Dust to the music videos of Missy Elliott.

LOA: Many of the stories in The Black Fantastic treat genre a jumping-off point for bold stylistic or thought experiments, using familiar SF or horror tropes as tools to create moments of irony, discomfort, and revelation. What is the role of genre in these tales?

andré m. carrington: Violet Allen’s story in this collection, “The Venus Effect,” is a tour de force in this way. It deliberately shifts from one genre to another while trying to evade the pitfalls Black people encounter in realistic situations.

And then, in a total 180-degree turn, Alex Smith’s story “Last Flight of the Unicorn Girl” is a superhero story, but you wouldn’t expect it from the way it starts.

These two pieces are great commentaries on how we take the plots of certain kinds of stories for granted just because they feature certain kinds of people. Here, that assumption gets turned on its head.

1834 illustration of enslaved people planting sugarcane in Antigua (CC0) and 1975 NASA illustration of a space colony (Public Domain)

LOA: Colonization, a familiar narrative template in SF, is reinterpreted and reversed in many of these stories. In your introduction, you note the special significance for Black writers in imagining historical contingencies playing out differently. Can you discuss the link between colonization and Afrofuturism, historical memory and futuristic recapitulation?

amc: This piece is complicated; obviously, Black people of the Diaspora and all African peoples have real histories with colonization. Fighting it has given us some of our most exciting examples of how to imagine and work toward liberatory futures.

In “All that Touches the Air,” the story by An Owomoyela, we get an imaginative account of humans living on a planet they’ve colonized encountering a radically different life form. I think that reflects how unprepared colonizing nations and empires have been, historically, for the complexity and sophistication of their fellow human beings and the environments that Indigenous peoples have made their homes. It’s not just “disease” or resistance that colonizers encounter. Life itself is hostile to colonialism, and it’s not even hostility all the time, but radical alterity. I think people familiar with colonial histories are good at telling stories about that.

In Afrofuturism, the ‘future’ doesn’t necessarily refer to a time that has yet to come. It’s more of a stand-in for the concept of a continuum between past, present, and future flowing through any given moment.

LOA: Despite these stories’ connections to the unreal and speculative, the physical body remains a constant presence, a reminder of human fragility, sensuality, might, and capacity for exploitation. Why are these writers interested in rendering the range and intensity of bodily experience?

amc: Wouldn’t it be amazing to have the creative skill some of these writers show when it comes to the human body? The stories “Habibi” by Tochi Onyebuchi and “The Malady of Need” by Kiini Ibura Salaam are intensely physical in a way that’s especially attentive to sensations and emotions. I can see in their writing an effort to convey how feelings live in the body, and how physical sensations can make mental phenomena—like relationships, freedom, oppression—truly real.

That interest can be inspiring, and lots of writers show it as a source of inspiration. Nicole Fleetwood’s curated exhibit and book, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, features many artists who emphasize the ways captivity enhances their perception of their own bodies and their awareness of how meaningful freedom of movement is. That’s another vein of creativity that Black speculative fiction authors tap into.

Images from MoMA PS1 exhibition of Nicole Fleetwood’s Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (markingtimeart.com)

LOA: Humor and satire run through this collection. What does the coexistence of comedy and catastrophe tell us about the Black imagination at work in these stories?

amc: Humor is everywhere in Black traditions, even in the bleakest situations. Thaddeus Howze’s story “Bludgeon” has one of the greatest twists. The humor in that piece arises from a situation where the survival of humanity is at stake, which shouldn’t be funny. But it’s also a sports story, which you might not expect as the setting for a science fiction, fate-of-the-world encounter.

P. Djèlí Clark’s story “The Secret Lives of the Nine Negro Teeth of George Washington” also features some twists of fate that amount to playing a very pointed joke on someone who deserves it. Unexpected attitudes arising in circumstances where you believe you know what to expect can give rise to humor, or horror, or mockery of the entertaining or cruel kind.

Set of George Washington’s false teeth (mountvernon.org)

LOA: It is rare for Library of America to publish a collection largely composed of living writers. Had you read many of these writers previously, or did you discover new voices in your research?

amc: This was my first experience editing fiction, and I am grateful that it’s a contemporary collection because connecting with these writers is an enormous privilege. I had read their work before, in most cases, but there were a couple whom I caught up with for the first time. In the course of reading what’s been published in themed collections, in magazines, and online over the past few years, I saw that the writers I already knew to be amazing are in the company of astonishing talents from all backgrounds. The only challenge was limiting how expansive this collection could be, given all the excellent work out there right now.

LOA: Despite the use of the term “Afrofuturism,” these stories are not just about the future, but the present and the past as well. What lies behind this transtemporal tendency, this bent toward counter-history?

amc: In Afrofuturism, the “future” doesn’t necessarily refer to a time that has yet to come. It’s more of a stand-in for the concept of a continuum between past, present, and future flowing through any given moment. I’ve always gone back to the contrast between the original “futurism” in the art world and the stark difference that Afrofuturism posits. The futurists from twentieth-century Italy were fascists. They wanted to eradicate the past in order to usher in the supremacy of a civilization they thought would conquer the world.

Afrofuturists have no truck with that. People of African descent have always drawn on history in diverse ways because we’re a diverse collection of peoples, and when we incorporate the influence of Diaspora and the survival of slavery into that history, we know that we have to use history differently in the present. That gives us an obligation to imagine the future, because we’ve been in positions where it was possible we might not have access to our past and might not have a future at all. Fascists can’t even imagine that: they glorify ignorance. Our creativity is so much more vital and so much more intellectually curious.

Samuel R. Delany (Jack Mitchell / Getty Images) and Octavia E. Butler (Patti Perret / The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens)

LOA: What are the origins of the contemporary surge in Afrofuturist fiction? In your introduction, you cite the work of Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany as critical antecedents. How did these authors and others shape or set in motion the works found in The Black Fantastic?

amc: A couple of breakthrough moments that helped open the markets for Black speculative fiction include Nalo Hopkinson’s and Tananarive Due’s successes, the rise of the music video, and the film Daughters of the Dust by Julie Dash.

Nalo is a phenomenon: her fiction draws from national and vernacular traditions that we don’t see elsewhere in English-language fantasy and science fiction despite the presence of Jamaicans throughout the English-speaking world. She’s empowered other Caribbean writers to bring their work to wider publics, and she’s inventive in a way that keeps surprising us. Tananarive Due is a horror icon who paved the way for Jordan Peele.

When I mention music videos, I’m leaning on the scholarship of Alex Weheliye, Katherine McKittrick, and Jasmine Strickland, who have all written about how artists like Missy Elliott popularized certain sonic and visual aesthetics in the entertainment industry that draw from Black people’s creative uses of technology and interpretations of movies and film. There are examples before that—Michael Jackson’s video oeuvre, obviously—but the less obvious examples that have made this moment possible are more important to acknowledge.

Still from Daughters of the Dust (dir. Julie Dash, 1991)

Julie Dash was the first Black woman to direct a globally distributed feature film. Daughters of the Dust, from 1991, tells an intergenerational story that lives in dream worlds and ancestral memory as well as oral history. It’s in the National Film Registry because it indelibly changed what was possible for that art form.

That’s Black speculative fiction. We wouldn’t have the flourishing landscape of Black artists doing futuristic and fantastical work in so many forms today without these forerunners.

LOA: Where can fans of the work in this collection look next? Are there other novels or collections you’d recommend for further exploring the universe of Afrofuturism or SF by Black authors?

amc: There’s a momentous legacy of Africanfuturism and African and Diasporic epic fantasy led by authors like Nnedi Okorafor and Marlon James. Nairobi is the place to look for artists defining the present: Jim Chuchu, Wanuri Kahiu, and the Nest Collective, to name a few.

Philadelphia is the future: Alex Smith, Rasheedah Phillips, Moor Mother. Ekow Eshun curated an exhibit under the heading “The Black Fantastic” showcasing Black artwork from across the globe that took the measure of what’s been done in recent years, which is one of the ways we knew the title of this anthology would resonate.

I’ll also recommend that people entertained by this collection take the opportunity to learn more from people in my profession: read Jemima Pierre and Peter Hudson on our histories and Tavia Nyong’o on our present and future. Take a class or join a book club. As exciting as it is to look for what’s next, it’s encouraging to look elsewhere and even right next door to see who is building Black futures.

Writers featured in The Black Fantastic: N. K. Jemison (photo: Laura Hanifin), P. Djèlí Clark (Michigan State University), and Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah (photo: Alex M. Philip)

andré m. carrington is the author of Speculative Blackness: The Future of Race in Science Fiction (2016). He is Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Riverside, where he directs the Speculative Fiction and Cultures of Science program.