Writing in the City Journal, Christopher Hitchens laments that America’s first-tier novelists have neglected Washington as the focus of their novels. “Can one imagine a Dickens without London or a Zola or Flaubert without Paris?” He dates the root cause of such oversight to the negotiations whereby Alexander Hamilton gave in to Thomas Jefferson’s desire for a capital near Virginia in exchange for Hamilton’s National Bank—American’s cultural and political capitals were thereby forever riven in twain.

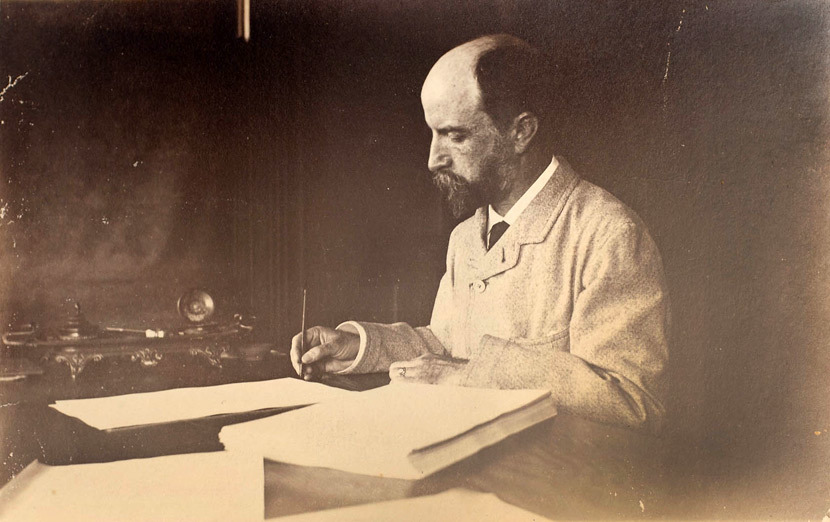

Hitchens finds the original model for the Washington novel in Henry Adams’s Democracy. Adams published it anonymously on April Fools’ Day 1880 and it became an immediate sensation, going through fifteen printings over the next thirty-five years before any edition carried his name. Guessing the identity of the author became a popular parlor game (much like what happened in 1996 with Primary Colors). John Hay, Clarence King, even Adams’s own wife were suspects. In 1911 Adams told a correspondent, “Really, of course, Henry James wrote it, in connection with his brother Willy, to illustrate Pragmatism.” The only correct guess came from the British novelist Mrs. Humphrey Ward.

Arthur Schlesinger testified to the novel’s staying power in The New York Review of Books in 2003:

People today read Democracy not as a roman á clef but as a gallery of political types and as a novel of political ideas. Adams . . . was less interested in portraying real personages than he was in defining Washington types—the unscrupulous politician, the naïve idealist, the lightweight reformer, the cynical diplomat, the cunning lobbyist, the congressional hangers-on. The cast of Adams’s Democracy populates Washington today, which is why the book is still in print. . . Democracy: An American Novel is all too true for Washington under corporate domination at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Many writers have attempted Washington novels since 1880 and in his article Hitchens catalogs several contenders: Norman Mailer’s Harlot’s Ghost; Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent; Christopher Buckley’s Wet Work; Thomas Mallon’s Fellow Travelers; Gore Vidal’s Lincoln, Burr, and The Golden Age; Ward Just’s Honor, Power, Riches, Fame, and the Love of Women and Echo House.

A bit of Googling reveals that the search for the great Washington novel has its own tradition. Mark Athitakis surveyed a number of candidates in 2008 and quoted Jeffrey Charis-Carlson, “a scholar of District literature”; “[The consensus is that] the great Washington novel is something of an oxymoron.” Writing about the decline of the Washington novel in The New York Times Book Review in 1995, Terry Teachout argued that “the best novels about American politics, Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men (1946), and Edwin O’Connor’s All in the Family (1966) and The Last Hurrah (1956) are, significantly, not about Washington at all.”

Bloggers Steven Riddle and Mark Judge, responding to Hitchens, question this assumption that novels about politics can really capture all of what Washington is. Riddle nominates Dinaw Mengestu’s The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears as “a very fine Washington novel” and Judge argues that if Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist is not a masterpiece it is certainly “a great, timeless novel.”

What should the Great Washington Novel be “about”? What novel about Washington have the critics missed? Is there not a candidate we can believe in?