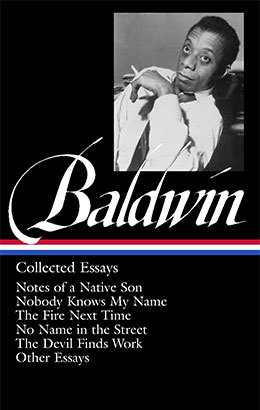

Today, February 18, marks the eightieth birthday of Toni Morrison, Nobel and Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist, editor, and educator. In 1998 Morrison edited two volumes of James Baldwin’s works for The Library of America: Early Novels & Stories and Collected Essays.

Although they were born just seven years apart, Morrison and Baldwin came from seemingly different generations of writers. They met in 1973 when Morrison was an editor at Random House and tried to sign Baldwin to a book deal. No contract ensued but they quickly became friends. “I dig Toni, and I trust her,” Baldwin wrote to his biographer David Adams Leeming.

Severely weakened by his battle with cancer, Baldwin spoke about Morrison to Quincy Troupe in November 1987, just three weeks before he died, in what would be his last interview:

Troupe: What do you think about Toni Morrison?Baldwin: Toni’s my ally and it’s really probably too complex to get into. She’s a black woman writer, which in the public domain makes it more difficult to talk about. . . . Her gift is in allegory. Tar Baby is an allegory. In fact all her novels are. But they’re hard to talk about in public. That’s where you get in trouble because her books and allegory are not always what it seems to be about. I was too occupied with my recent illness to deal with Beloved. But in general she’s taken a myth, or she takes what seems to be a myth, and turns it into something else. I don’t know how to put this—Beloved could be about the story of truth. She’s taken a whole lot of things and turned them upside down. Some of them—you recognize the truth in it. I think that Toni’s very painful to read.

Troupe: Painful?

Baldwin: Yes. Because it’s always or most times a horrifying allegory; but you recognize that it works. But you don’t really want to march through it. Sometimes people have a lot against Toni, but she’s got the most believing story of everybody—this rather elegant matron, whose intentions really are serious and, according to some people, lethal.

At Baldwin’s funeral service at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine on December 8, 1987, Morrison was one of several eulogists. Her remarks movingly described how indebted she felt to her friend:

The season was always Christmas with you there and . . . you did not neglect to bring at least three gifts. . . You gave me a language to dwell in, a gift so perfect it seems my own invention. . . . The second gift was your courage, which you let us share: the courage of one who could go as a stranger in the village and transform the distances between people into intimacy with the whole world. . . The third gift was hard to fathom and even harder to accept. It was your tenderness – a tenderness so delicate I thought it could not last, but last it did and envelop me it did.

You knew, didn’t you, how I needed your language and the mind that formed it? How I relied on your fierce courage to tame wildernesses for me? How strengthened I was by the certainty that came from knowing you would never hurt me? You knew, didn’t you, how I loved your love? You knew. This then is no calamity. No, This is jubilee. “Our crown,” you said, “has already been bought and paid for. All we have to do,” you said, “is wear it.”

And we do, Jimmy. You crowned us.