Guest blog post by John Schulian, co-editor of At the Fights: American Writers on Boxing

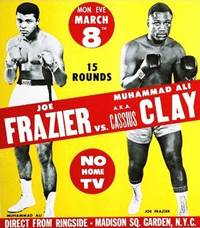

It seems like only a heartbeat ago that Frank Sinatra was ringside at Madison Square Garden, camera in hand, straining to get just the right shot of Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier as they went to war for the first time. The calendar tells us, however, that forty years have passed. Sinatra is gone. So is Life magazine, which made him part of the working press for the night that launched boxing’s greatest trilogy. Ali and Frazier dwell in retirement like battleships that were too long at sea, but in our memories, they are forever young. That’s the curious thing about what they did for a living: they destroyed each other and gained immortality.

The two of them had been friends before their violent Garden party. When Ali was stripped of his heavyweight championship in 1967 for refusing induction into the military and found himself wandering the college lecture circuit, Frazier loaned him money. It was a fitting gesture, for Frazier now wore the crown that had been Ali’s. But he vowed he would give the deposed champ a chance to win it back, and when Ali was allowed to return to the ring in 1970, Frazier did something that isn’t standard practice in the cutthroat world of boxing. He kept his word.

They would each make $2.5 million and fight in front of a Garden crowd that overflowed with celebrities. Burt Lancaster, Sinatra’s co-star in From Here to Eternity, did the radio commentary. But the only thing that really mattered was the hatred that had erupted when Ali called Frazier an Uncle Tom and a tool of good-old-boy sheriffs and Ku Klux Klansmen. In a lifetime filled with kindness as well as greatness, it was a low moment for Ali. He knew full well that Frazier, the thirteenth child born to a one-armed North Carolina sharecropper, had traveled a far harder road than he had. By comparison, Ali was a child of privilege, raised in relative comfort in Louisville, his boxing career bankrolled by local white businessmen. But he got away with it because he was handsome, charming, funny, all the things Frazier was not.

What Frazier was, was mad enough to kill. Even in the early rounds of the fight, when Ali’s punches were turning his face into a Halloween mask, Frazier kept coming, relentlessly hammering away at Ali’s body. Here was a man bent on destruction, and in the eleventh round he delivered the blow that should have achieved his goal, a left hook that would have dropped a horse or maybe even a brick wall. But Ali didn’t fall. He wobbled and survived to fight on into the fifteenth and final round. Then Frazier clouted him with another, even more brutal left hook. This time Ali fell like a cartoon character, landing flat on his back while his feet flew high in the air. But he got up. The right side of his face had begun to swell and he was guaranteed to lose, but damned if he was going to let himself be knocked out.

By somehow getting back to his feet in the waning moments of a fight that sent both men to the hospital, Ali underscored his greatness for the nation, the world, and, most of all, Frazier. He would go on to win both their forgettable second fight and the epochal “Thrilla in Manila,” and he would leave pieces of himself along the way, as would Frazier. And when the last punch was thrown, it could rightfully be asked where the physical had ended and the metaphysical had begun. Only Ali knows for sure, but these days he doesn’t talk much.

Video: Highlights of Ali–Frazier I

Library of America’s anthology At the Fights: American Writers on Boxing includes seven articles on Ali, including Mark Kram’s classic account of the “Thrilla in Manila,” the final Ali–Frazier match. A. J. Liebling: The Sweet Science and Other Writings includes Liebling’s account of a 1963 Cassius Clay fight at the Garden.