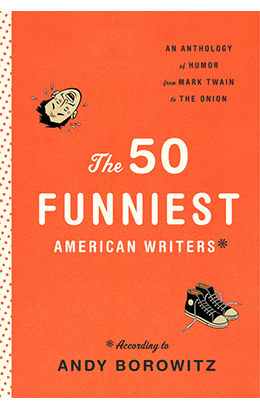

Comedian Andy Borowitz, who is the author of six books and who reaches millions of readers worldwide through the Borowitz Report, recently spoke with us about The 50 Funniest American Writers, the new anthology of humor writing that he edited for The Library of America and which is available today from booksellers everywhere.

Library of America: How and when did you first get interested in humor writing?

Andy Borowitz: I started getting interested in comedy when I was around ten. I grew up in Cleveland, and there was a revival house called The Old Mayfield that showed classic comedy films: the Marx Brothers, Chaplin, Harold Lloyd. My dad used to take me to see them on Sunday nights. Around this time—the late 1960s—Woody Allen started coming out with his first comedies, Take the Money and Run and Bananas. I started reading Allen’s collections of prose humor and began writing full-length parodies of detective novels. So I was very into it by the time I was eleven or twelve.

LOA: Which writers most influenced you along the way?

Borowitz: Besides Woody Allen, Ian Frazier’s writing for The New Yorker had a big impact on me. In high school I read The Magic Christian by Terry Southern, which I still think might be the funniest American comic novel. But I can’t say that Terry Southern’s style influenced me so much as it just flat-out made me laugh.

LOA: Why fifty writers?

Borowitz: Well, of course, fifty is a totally arbitrary number. I started with a list of 100 (another arbitrary number) and the Library of America helped me whittle it down to fifty—the theory being that the resulting list would be more selective and the book itself would be more compact. I’m very happy with that decision, what with brevity being the soul of wit and all that.

LOA: Why does 50 Funniest American Writers jump from Mark Twain in 1879 to George Ade in 1904? Was there only one funny American in the nineteenth century? And why so many recent writers?

Borowitz: The period from 1879 to 1904 in America was known as “The Era of Bad Feelings,” in which everyone was grumpy and no one said or wrote anything remotely funny. Actually, that’s a lie. The book is very heavily tilted toward more recent writers because I wanted it to be entertaining to today’s readers. With the exception of Mark Twain, very little humor writing of the nineteenth century resonates today, in my opinion. And since I edited the book, my opinion is the only one that really matters, right?

LOA: Are American writers funnier than writers in other countries?

Borowitz: I have no idea, since I don’t read many other languages, although something tells me we won’t be seeing The 50 Funniest North Korean Writers any time soon.

LOA: You’ve written for TV, movies, theater, and standup in addition to writing for print publication. Are there significant differences between what works in these different media, and did this influence/affect the choices for the book?

Borowitz: They’re all different. The most obvious difference is that in theatrical media—film, stage, standup—the actual performance is so key to what makes something funny. I had experiences as a writer when I’d write a script that everyone thought was funny when they read it but then fell flat when an actor tried to perform it. Conversely, some scripts don’t make you laugh at all but when you see them performed you’re in tears. So in compiling the book I tried to take anything performance-based off the table and focused on material that was meant to be read. There are some exceptions—some writing by stand-ups like George Carlin and Lenny Bruce are included—but my arbitrary requirement was that their work had to be published in prose form in order to be considered. As it stands, I think the writing by stand-ups that I’ve included works as prose humor, so I’m happy with those choices.

LOA: Do you notice any particular trends or themes emerging from the book, maybe even things you didn’t expect?

Borowitz: Writers are drawn to the same formats again and again and again. The Onion is famous for writing parody news, but Veronica Geng did it, too. Dozens of writers have parodied advice columns, and I’ve included two by Charles Portis and George Saunders. Dorothy Parker wrote wonderful stream-of-conscious monologues, and decades later, Jenny Allen is doing just that. The expression that there’s nothing new under the sun is true—including that expression.

LOA: What was your greatest discovery in the course of putting the book together?

Borowitz: Langston Hughes was funny. When people look at the list of the fifty funniest Americans, they sometimes think I’m out of my mind for including him. But then, they haven’t read his “Simple” stories, and I hadn’t read them before I started working on the book. There are other so-called “serious” writers, like Sinclair Lewis, who are in the book because they were capable of truly funny writing. The idea of categorizing writers as “serious” or “funny” seems kind of simplistic to me. Was Evelyn Waugh a serious writer or a funny one—and while we’re on the subject, how about Shakespeare? I’m glad I was able to include Hughes and Lewis in the collection, even if they don’t seem like the most obvious candidates for the fifty funniest.

LOA: What about the greatest disappointment—the writer or piece you were sure would work but didn’t?

Borowitz: Some of our greatest comic novelists—Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Heller, Carl Hiaasen, and Donald Westlake, to name four—aren’t in here. I think it’s hard to excerpt ten pages from a comic novel and capture what’s funny about the larger work. I’m already catching hell from Vonnegut fans! But the Library of America has already brought out one volume of Vonnegut and is bringing out another, so maybe all will be right with the world.