Robert Polito, director of the Graduate Writing Program at the New School, author of the National Book Critics Circle award–winning Savage Art: A Biography of Jim Thompson, recently spoke with us about David Goodis: Five Noir Novels of the 1940s and 50s, which he edited for The Library of America.

LOA: What was David Goodis’s unique contribution to American crime fiction?

Polito: If Hammett and Chandler might be said to head up the great initial wave of American crime novels with a focus on the detective, then Jim Thompson, David Goodis, and Patricia Highsmith spanned the next crucial wave, let’s call it the nouvelle vague, where the attention tilts to the criminal. Highsmith reinvented the lost-American-in-Europe novel out of Hawthorne and James for crime fiction, Thompson devised those astonishing self-consuming experimental fiction structures. But Goodis to my ear crafted the sharpest sentences. Listen to this bit from Dark Passage:

[Vincent Parry] began to remember the days of work, the day he had started there, how difficult it was at first, how hard he had tried, how he had taken a correspondence course in statistics shortly after his marriage, hoping he could get a grasp on statistics and ultimately step up to forty-five a week as a statistician. But the correspondence course gave him more questions than answers and finally he had to give it up. He remembered the night he wrote the letter telling them to stop sending the mimeographed sheets. He showed the letter to Gert and she told him he would never get anywhere. She went out that night. He remembered he hoped she would never come back and he was afraid she would never come back because there was something about her that got him at times and he wished there was something about him that got her. He knew there was nothing about him that got her and he wondered why she didn’t pick herself up and walk out once and for all. She was always talking in terms of tall bony men with high cheekbones and hollow cheeks and very tall. He was bony and very thin and he had high cheekbones and hollow cheeks but he wasn’t tall. He was really a miniature of what she really wanted. And because she couldn’t get a permanent hold on the genuine she figured she might as well stay with the miniature.

Those little repeated phrases are the bars of the psychic prison Parry lives inside, and the only other writer I know who sounds this way is Gertrude Stein in The Making of Americans.

LOA: Is Goodis a pulp writer? A hard-boiled writer?

Polito: David Goodis literally was a pulp writer when he started out writing fiction in the late 1930s, publishing by his own estimation five million words in five years in magazines with titles like Wings, Battle Birds, Fighting Aces, The Lone Eagle, Gangland Detective Stories, True Gangster Stories, Detective Fiction Weekly, 10 Story Western, Air War, New Detective Magazine, Double-Action Detective, Popular Sports Magazine, Sinister Stories, Thrilling Western, Dime Western, Captain Combat, G-Men Detective, and Dime Detective, among others. His stories appeared under his own name and probably under a half-dozen pseudonyms (including Lance Kermit, Logan C. Claybourne, Ray. P. Shotwell, and David Crewe). Some of the novels in this Library of America Goodis volume were paperback originals, others first appeared in hardcover. But neither in those early pulp stories nor in his classic novels would I style him a hard-boiled writer. Melancholy and yearning were his notes, not toughness and violence.

LOA: Why has he remained mainly a cult figure?

Polito: Good question—Goodis always seems poised for rediscovery, and he’s virtually the cult figure’s cult figure, such that Jean-Luc Godard can slyly name a character in Made in U.S.A. “David Goodis,” as though the words are part of a secret code. So many American crime writers mask their root sadness in stoicism, or in rote tough-guy, inverse sentimentality. But Goodis just puts the sadness and loss out there. Here is the opening to his first novel, Retreat from Oblivion:

After a while it gets so bad that you want to stop the whole business. You figure that there’s no use in trying to fight back. Things are set dead against you and the sooner you give up the better. It’s like a mile run. You’re back there in seventh place and there isn’t a chance in the world. The feet are burning, the lungs are bursting, and all you want to do is fall down and take a rest.

Goodis was twenty-two when he published that, a year out of Temple University. If Jim Thompson for all his narrative brilliance is too violent for some readers, maybe Goodis is just too sad. Yet I always hear so much wit and exuberance, even joy, in the cunning rhythms of his lines. Let’s hope that this is now his moment.

LOA: Why do you think his books have appealed so much to filmmakers?

Polito: It’s probably not the plots, since often the films alter his plots. Classic noir fiction, and Goodis is an exemplar of this quality, might be summed up as all those beautiful sentences telling you the most terrible things. Classic noir film also is all about insinuating mood and atmosphere, and Goodis was the maestro of moody, atmospheric insinuation.

LOA: Is it ironic that the work of a Philadelphia writer should be best known to Americans in a French movie version?

Polito: Another in the long line of American-French ironies, I suppose. I think Goodis was America for Godard and Truffaut, and the tangle of webbing connecting American crime fiction to such French phenomena as existentialism is strong and obvious. Recently I was struck again by a fascinating moment in Pauline Kael’s famous 1967 review of Bonnie and Clyde [included in the recent LOA collection, The Age of Movies—ed.]. There Kael proposes that, “If this way of holding more than one attitude toward life is already familiar to us—if we recognize the make-believe robbers whose toy guns produce real blood, and the Keystone cops who shoot them dead, from Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player and Godard’s gangster pictures, Breathless and Band of Outsiders—it’s because the young French directors discovered the poetry of crime in American life (from our movies) and showed the Americans how to put it on the screen in a new ‘existential’ way. Melodramas and gangster movies and comedies were always more our speed than ‘prestigious,’ ‘distinguished’ pictures; the French directors who grew up on American pictures found poetry in our fast action, laconic speech, plain gestures. And because they understood that you don’t express your love of life by denying the comedy or horror of it, they brought out the poetry in our tawdry subjects.” That captures something vital, I think, in the America to France and then back to America circuit of someone like David Goodis.

LOA: Do you have a particular favorite among the five novels collected here?

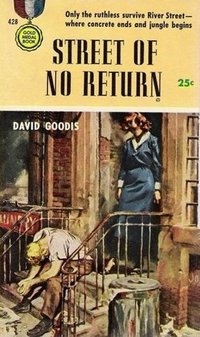

Polito: Probably Street of No Return, perhaps his most Beckett-like novel, issued by Gold Medal coincidentally the same year as the first English publication of Waiting for Godot, another story of some tramps who wind up back where they started.

LOA: How did you discover Goodis yourself?

Polito: Early on I discovered him without knowing that it was Goodis I was experiencing through the movies Shoot the Piano Player and Dark Passage. But I first read the novels in the 1980s, after Barry Gifford started reissuing them for Creative Arts/Black Lizard. Which means, in a real sense, I discovered David Goodis through Geoffrey O’Brien, the editor-in-chief of the Library of America, since Geoffrey wrote the beautiful introductions to those Goodis reissues.