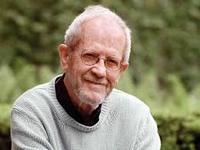

Elmore Leonard died on August 20 at the age of 87. In the months before his death he had been working on his 46th novel. He had also been looking forward to the publication of the Library of America edition of his best fiction and had given his final approval to the selection of novels for three LOA volumes. (The first collection, scheduled to appear in September 2014, gathers four novels, all set in Detroit and published in the 1970s).

A decade ago, on April 8, 2002, Leonard was one of six prominent writers who delivered a few remarks at the twentieth-anniversary celebration of The Library of America, which took place at the The Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City. Joining him on the stage were Gail Buckley, Michael Cunningham, Richard Price, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and Wendy Wasserstein. The presenters were asked to speak about writers from the LOA series for whom they feel a special affinity. Leonard chose John Steinbeck, and his remarks appear below.

I’m not certain how academic critics rate John Steinbeck, perhaps not up there with Hemingway and Faulkner, but I honor him today because fifty years ago he set me free. It was one book in particular, Sweet Thursday, published in 1954, that did the job.

I’ll never forget the scene in which Doc, the marine biologist, sits down to write.

Doc bought a package of yellow pads and two dozen pencils. He laid them out on his desk, the pencils sharpened to needle points and lined up like yellow soldiers. At the top of a page he printed: OBSERVATIONS AND SPECULATIONS. His pencil point broke. He took up another and drew lace around the O and the B, made a block letter out of the S and put fish hooks on each end. His ankle itched. He rolled down his sock and scratched, and that made his ear itch. “Someone’s talking about me,” he said and looked at the yellow pad. He wondered if he had fed the cotton rats. It is easy to forget when you’re thinking.

He feeds the rats and remembers he hasn’t eaten.

When he finished a page or two he would fry some eggs. But wouldn’t it be better to eat first so that his flow of thought would not be interrupted later? . . . He fried two eggs and ate them, staring at the yellow pad under the hanging light. The light was too bright. It reflected painfully on the paper. Doc finished his eggs, got out a sheet of tracing paper, and taped it to the bottom of the shade below the globe. It took time to make it neat. He sat in front of the yellow pad again and drew lace around all the letters of the title, tore off the page, and threw it away. Five pencil points were broken now. He sharpened them and lined them up with their brothers.

Doc looks out the window to see a car drive past and a girl come out of the Bear Flag and walk along Cannery Row.

He writes a few lines after observing the way the girl walks, with pride but not vanity. And his pencil point breaks. “He took another, and it broke with a jerk, making a little tear in the paper. He read what he had written; dull, desiccated, he thought.” The scene ends with Doc getting up and going across the street for a beer.

It amazes me that a writer as renowned as Steinbeck knew the tricks of putting off writing. I’ve found myself paying bills—and that might’ve been, un- or sub-consciously, an incentive to get to work. It encourages me that it was part of writing and not a disease.

But what encouraged me much more is in the prologue of Sweet Thursday. A character, Mack from Cannery Row, says he was never satisfied with that book. He says,

I would of went about it different. . . . I like a lot of talk in a book, and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks. And another thing—I kind of like to figure out what he’s thinking by what he says. I like some description too . . . I like to know what color a thing is, how it smells and maybe how it looks, and maybe how a guy feels about it—but not too much of that . . . Sometimes I want a book to break loose with a bunch of hooptedoodle. The guy’s writing it, give him a chance to spin up some pretty words maybe, or sing a little song with language. That’s nice. But I wish it was set aside so I don’t have to read it. I don’t want hooptedoodle to get mixed up in the story.

He suggests putting it right at first or in chapters, which Steinbeck did in Sweet Thursday. Chapters 3 and 38 have headings: Hooptedoodle one and two.

That became the backbone of my tendrils for success and happiness in writing fiction: mainly don’t describe too much, unless you really know what you’re doing. In my rules, I say “These are rules I picked up along the way to help me remain invisible while I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story.” And if you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over. For me that is what John Steinbeck inspired, the simplicity that if you can’t do it well, don’t do it. If you can do something well . . . from that time on, 1954, I concentrated on telling my stories in dialogue so I wouldn’t have to describe the characters.