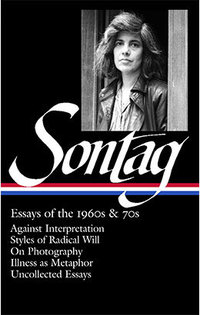

The author of Swimming in a Sea of Death: A Son’s Memoir (among many other books) and the editor of the journals and notebooks of Susan Sontag, David Rieff spoke with us recently about Susan Sontag: Essays of the 1960s & 70s, the collection of his mother’s writing that he edited for the LOA.

LOA: In Sontag’s view, who were the most important European writers undiscovered or neglected in the U.S.? Did she think of herself as a critic who bridged the intellectual worlds of Europe and America?

Rieff: As an American, my mother was uncompromisingly engaged in the great political issues of her time—the Vietnam War, feminism, American power after the Cold War. But as a writer, and without denying or repudiating her “American-ness,” my mother saw herself as an international person, if you will, a citizen of the Republic of Letters—an idea that, while of course she knew it to be metaphoric, counted for her. So the idea that the U.S. and Europe were two separate and distinct worlds did not make much sense to her. That said, as someone steeped in French culture particularly, early in her career she brought writers like Nathalie Sarraute, Roland Barthes, E. M. Cioran, and others to the attention of New York publishers. Later in her career, my mother often offered to write prefaces to works she hoped U.S. publishers would have translated.

LOA: The seminal essay “On Photography” changed the way people thought and wrote about photographs. What led Sontag to her interest in photography?

Rieff: I don’t believe there was one event. In cultural terms, at least, and perhaps in others as well, my mother was interested in virtually all the arts, not only photography. I simply think, as with many writers, there were some subjects about which she felt she had a great deal to say (like photography) and others, such as, for example, ballet, which she loved and followed, where her relations to them was as a devotee rather than as a critic.

LOA: Several of the previously uncollected pieces in the volume explore cultural attitudes toward women, beauty, and aging, speaking to issues central to the emerging women’s movement. Did Sontag identify herself as a feminist?

Rieff: Unquestionably. But what my mother meant by identifying herself as a feminist and what others wanted her to mean by it, were two very different things.

LOA: Did Sontag have any personal favorites among these essays?

Rieff: I think like most writers, my mother liked best the essay she was working on at the time. She was not a great one for looking backwards in any domain of life, including her own work.

LOA: How, in Sontag’s view, were her essays related to her other work (fiction, filmmaking, playwriting, etc.)?

Rieff: I don’t think she thought in such terms. I do know that she treasured her identity as a novelist and short story writer, and at least in some ways, valued it above that of all her work in other genres. But this was a feeling, not a judgment or any sort of demotion of her work as an essayist, filmmaker, playwright, etc.